SYDNEY: Big city gaybourhoods: where they come from and why they still matterIn London, there is Soho; in New York, Chelsea and Greenwich Village; and in San Francisco, there is the Castro. In Sydney, there is Darlinghurst and, more specifically, Oxford Street. These are neighbourhoods of large cities that have, since at least the 1950s and often earlier, developed a reputation as queer spaces.

In more recent years, those reputations have begun to fade and the enduring meanings of the “gaybourhood” have come into question.

But what each of these places represents is the centrality of urban space to the emergence of visible, “out and proud” lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer identities and communities.

The 1978 Mardi Gras march was a key moment for queer urban visibility. AAP/Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

Queer Sydney in the ‘Golden Mile’ era

The peak years of Oxford Street’s queer life extended from the mid-1970s until the mid-1990s. In the years after the second world war, many gay men in Sydney socialised in CBD hotels, including the Hotel Australia.

A guide to the ‘Golden Mile’ published in the Oxford Weekender News, one of many ‘bar rag’ newspapers that circulated the 1980s queer scene. Author provided

The first LGBTQ clubs on Oxford Street were Ivy’s Birdcage and Capriccio’s, which both opened in 1969. By the beginning of the 1980s, Oxford Street was home to a string of bars, clubs, saunas and cafes and had become known as Sydney’s gay “Golden Mile”.

The emergence of this gay heartland represents extraordinary social change. Male homosexuality remained illegal in New South Wales until 1984. The homosexual men socialising in 1950s CBD hotels were required to do so with discretion – the consequences of discovery could be devastating.

In contrast, the queerness of a venue like Capriccio’s was defiantly visible and undeniable. As more venues were opened along the Golden Mile, the street itself became a gay space, as did the surrounding neighbourhoods where LGBTQ people – particularly gay men – made homes in the terraces and apartments of Darlinghurst and Paddington.

A simple walk along the street became an act of participation in an emerging community.

Ivy’s Birdcage at 191 Oxford Street was one of Darlinghurst’s first drag bars. Sydney Pride History Group, Author provided

Members of a marginalised social group were thus using urban space to resist oppression and build a community. For some, this produced a kind of utopia. In an interview with Sydney’s Pride History Group, DJ Stephen Allkins described his first visit to the Oxford Street disco Patch’s as a teenager in 1976. He remembers:

I was home. That was it. It was the most fabulous place I’d ever been in my life … It’s full of gay people and they’re all dressed to the nines. They’re not hiding under a rock … They’re expressing and happy.

Finding a place in the Queer community

But these feelings of joy at having found such a space can be complicated by a range of factors. The gay community was certainly not free from sexism, racism and transphobia, meaning that some within the LGBTQ community were granted far easier access to these spaces than others.

Indeed, although Golden Mile-era Oxford Street included venues popular with lesbians, including the women-only bar Ruby Reds, the surrounding neighbourhood was more identifiably gay than lesbian.

Inner-west suburbs including Leichhardt and Petersham were far more significant urban spaces in the lives of many queer women. Lesbian share-houses in these neighbourhoods became central sites of feminist politics, activism, sex and romance.

Penny Gulliver, a resident of legendary 1970s share-house “Crystal Street”, has remembered that women “who were just coming out, because there was nothing like a counselling service then, they’d come to Crystal Street”.

Into the new millennium, Oxford Street’s place as the gay heart of Sydney became less certain. As LGBTQ businesses failed and venues closed, questions emerged as to whether a community now more a part of the mainstream still needed its own spaces.

For a time, King Street in Newtown dominated as a queer alternative. In 1983 gay publican Barry Cecchini took over the Milton Hotel on Newtown’s King Street, renamed it Cecchini’s and launched it as the area’s first gay venue. Shortly after, the Newtown Hotel, just across the road, also became a gay pub. Cecchini told the Sydney Morning Herald in 1984 that gays were leaving “the scene” of Oxford Street looking for a “more cosmopolitan mix” in Newtown.

Through the following decades, venues including The Imperial in Erskineville (made famous as the site from which three drag queens launched their adventures in a bus named Priscilla) and the Sly Fox in Enmore, home to a popular lesbian night, further developed the area’s queer reputation.

Protecting Queer space

In recent years, however, a range of factors, including changes to licensing laws, have produced significant challenges for queer socialising in that neighbourhood.

Newtown sits outside the zone of the so-called “lockout laws”. Late-night partiers who might once have ventured to Kings Cross are instead heading to pubs along King Street, and reports of anti-LGBTQ abuse and violence have increased.

In response, a campaign called “Keep Newtown Weird and Safe” has attempted to maintain the queer meanings of this urban space.

Despite changes in Oxford and King streets, efforts to keep Newtown “weird” highlight the continued value of urban space to LGBTQ communities. Indeed, among a younger generation, new forms of queer identity continue to inspire the search for spaces in which to celebrate difference.

In pockets of the inner west, for example, young queer, transgender and genderqueer people are creating spaces of activism, partying, performance and everyday life. This new generation is exploring the fresh possibilities of queer identity and developing their community. Access to urban space remains central to this.

Like the city itself, the LGBTQ community continues to be less a fixed entity than a process of movement, adaptation and change.

MELBOURNE: Gay Old Time

An asio report from the 1950s, Homosexuals as Security Risks, includes information from an anonymous man about Melbourne’s secret gay subculture. As well as educating the authorities about queer terminology, the source expresses his hope “to find an affectionate, stable and confiding relationship with another homosexual”. The prospect, he acknowledges, is “a probably unattainable dream-wish”.

His account appears in Camp as . . . Melbourne in the 1950s, a Midsumma Festival exhibition. Through photographs, interviews and historical documents, Camp as provides an insight into what homosexual life was like during a grimly repressive era in which gay men and women had reason to cower in the closet.

Homosexuality was not only socially unacceptable in the 1950s, it was also a criminal offence. By 1957 the state vice squad had dedicated a third of its resources to cracking down on what it perceived as a growing problem in Victoria. Throughout the decade, the number of those arrested and jailed continued to grow as officers raided parties or entrapped gay men in public toilets and other popular beats.

Meanwhile, the Truth newspaper attempted to whip up moral outrage by running lurid scare stories about “prowling pests” and “park menaces”. But Graham Willett, a Melbourne University lecturer and curator of the exhibition, suggests that, despite the fear of discrimination and arrest, a tight-knit gay community still evolved during the 1950s. “We’ve constructed this image of Melbourne back then as this terrible place,” he says, “But what’s quite amazing is that people managed, through courage or circumstances, to find ways of meeting other people like themselves and constructing reasonably nice lives.”

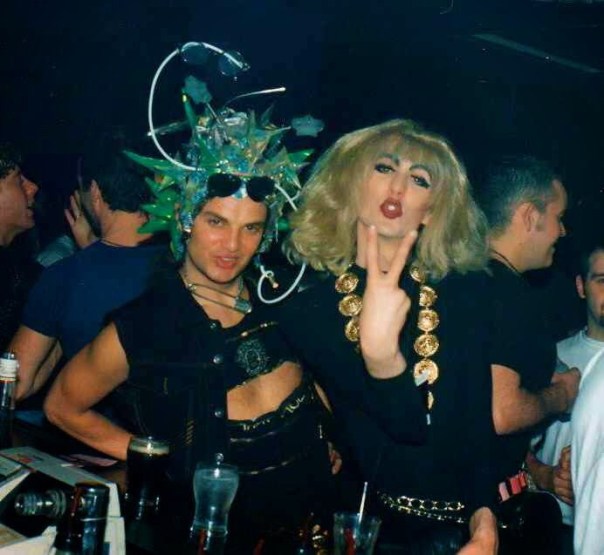

Certainly the exhibition challenges the assumption that gay people of the period led lonely, desperate lives. In one photo, for example, a drag queen flounces defiantly about the stage wearing a pink dress and a flower in his hair. “In the ’50s there was no gay scene in a public way,” Willett says, “but there were still places you could go to in the city that accepted the presence of gay men.”

One of the most surprising gay sanctuaries was the Myer department store, thanks to the director of the store’s display unit, Freddie Asmussen, whose sexuality was an open secret. Bald and bespectacled, Asmussen was renowned for the extravagant decor of his South Yarra home, which boasted 13 chandeliers, a black-and-silver dining room and a colour-coded garden in which he would tolerate only white flowers. His willingness to employ young men of a similar sexual orientation turned Myer into an unlikely haven for the gay community.

Hotel Australia on Collins Street was the closest that Melbourne had to a gay bar. The upstairs area catered to a smart, discreet crowd while the downstairs bar, known as “the snake pit”, was aimed at rough trade. An alternative was Val’s, a bohemian coffee lounge on Swanston Street, with a royal-blue carpet and mauve furniture. Val was a flamboyant lesbian who walked the streets dressed in a homburg hat and tailored suit while brandishing a silver-topped cane.

Willett says that during this era there was more pressure on lesbians to conform to these stereotypes. “Lots of women talk about living as butches or femmes in the ’50s and ’60s,” he says. “But women’s liberation challenged a lot of that. It said, ‘You can be what you want to be. You don’t have to conform to these roles.’ ”

Other fragments of queer culture featured in the exhibition are similarly blatant. In the Australian Gay and Lesbian Archives, Willett discovered a stash of magazines promoting body building as a form of homoerotic stimulation. The cartoons in Physique Pictorial devise utterly ridiculous situations to justify the inevitable displays of male nudity. One features a muscle-bound builder, who falls off a roof and lands on a pile of nails, thereby requiring his workmate to extract them from his buttocks. “It just gets more and more camp,” Willett admits.

The brazen nature of such material would seem to suggest a growing confidence within the community. And yet during the 1950s there was just a single attempt to challenge the legal status quo that failed to gain sufficient support. “For most of these people, the idea of changing the law would have seemed impossible,” Willett says. “It would have just seemed inconceivable that you would do that.”

The gay-rights movement only began to emerge in Australia in the 1960s, developing as part of a broader liberal trend that also sought reform on social issues such as abortion, censorship and Aboriginal rights. Victoria didn’t decriminalise homosexuality until 1980, while Tasmania didn’t suit until 1997. Over the past 50 years, gay culture has undergone a makeover as radical as anything on Queer Eye For A Straight Guy. By exploring the formative days of the community, Willett’s exhibition reinforces how much has changed, while presenting an intriguing social history of Melbourne’s secret past.

CANADA & NORTH AMERICA: Dwindling gaybourhoods

Author Amin Ghaziani looks into the future of North American gay villages

Credit: Paul Dotey

Four and a half years ago, Shawn Ewing and her wife left their apartment in Vancouver’s West End to move to the suburbs. For the Ewings, leaving the gaybourhood for Surrey was a question of simple math.

“Two thousand square feet and a yard versus a little under 700 feet in an apartment,” she says. “Accessibility to the party downtown wasn’t important to us anymore. What was important was a house and having a yard and a garden and all of that good stuff.”

Ewing, a former president of the Vancouver Pride Society, is now vice-president of Surrey’s Pride organization. She says that despite Surrey’s conservative reputation and some early fears that they might have to “straighten up,” her family has had no problems at all.

“We haven’t changed any of our behaviour,” she says. “I don’t have a problem holding my wife’s hand when we’re walking down the street or giving her a kiss in my front yard.”

“I probably got called out more living downtown about being a dyke than I certainly have been in Surrey,” she says.

From Vancouver’s Davie Village to Toronto’s Church Street to Montreal’s Le Village, everyone has their own opinion about Canada’s gay neighbourhoods, but few seem to disagree that they are in decline.

Whichever name you call it — the gaybourhood, gayvenue, gay district, gay mecca, gay ghetto — the question of its future isn’t limited to Canada. Across the border in the United States, many notable gay districts are also fading into shadows of their former selves, from San Francisco’s Castro to Chicago’s Boystown to Seattle’s Capitol Hill to countless more.

In his recently released book There Goes the Gayborhood?, Amin Ghaziani, an associate professor of sociology at the University of British Columbia, examines the changing face of the gay neighbourhood. His research is based on census data, opinion polls, more than 600 newspaper articles and more than 100 interviews with gaybourhood residents.

“I myself lived in Chicago’s Boystown district for nearly a decade, starting in 1999. I remember feeling uneasy in those years as I read one headline after another about the alleged demise of my home and other gayborhoods across the country. The sight of more straight bodies on the streets became a daily topic of conversation among my friends — an obsession to be honest,” Ghaziani writes.

“As the years went by, my friends and I bemoaned, perhaps most of all, feeling a little less safe holding hands with our partners, dates, or hookups — even as we walked down what were supposed to be our sheltered streets. I had been called a ‘fag’ on more occasions than I still care to remember, and I was shocked at the disapproving looks that I would receive when walking hand in hand with another man. I knew I could not escape this menacing straight gaze altogether, but I was so angry that I had to deal with it in Boystown. This was supposed to be a safe place,” he writes.

According to statistics, the days where the gay community was drawn to live and work in a single neighbourhood are ending. American census data shows that same-sex-couple households have become “less segregated and less spatially isolated across the United States from 2000 to 2010,” Ghaziani writes. “This is a restlessness that clearly appears in cities across North America. To wonder where gayborhoods are going, debate whether they are worth saving, or question their cultural resonance — all of this announces to us that they are in danger.”

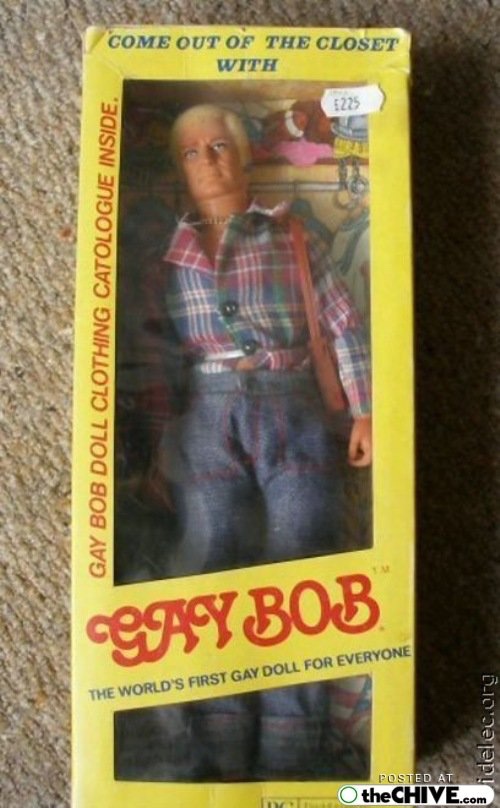

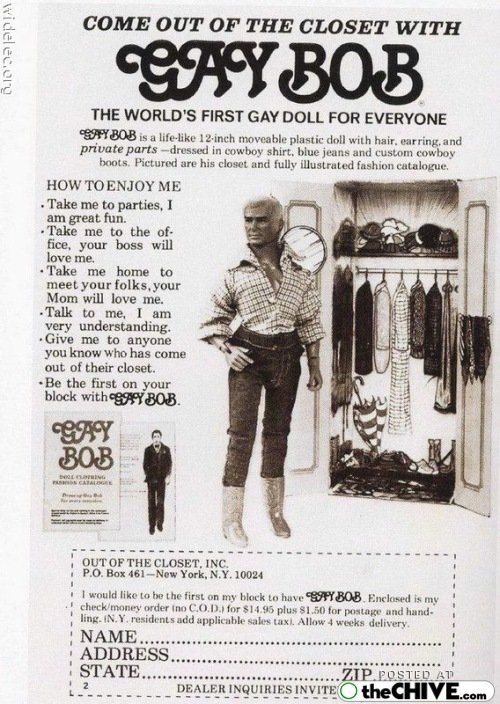

Although gay bars have been around since the start of the 1900s, gaybourhoods are a fairly recent phenomenon. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that they really began to flourish in North America, buoyed first by the thousands of men and women dishonourably discharged from the military for their presumed homosexuality and later by migrating single gay men and lesbians from smaller towns in search of a place to call home. Gaybourhoods promised safety and freedom, as well as places to find love and sex.

Ghaziani points to several factors that are changing these areas today: the increased acceptance of gay men and lesbians by society and under the law, allowing many people to feel safer moving to more spacious accommodations in the suburbs; growing development and gentrification, leading to rising property value and rents, driving some people out of downtown areas; and the increased migration of straight people back into desirable urban areas.

Ron Dutton has lived in Vancouver’s West End for 40 years and has never once wanted to leave. “I like the diversity of people, the sense of openness,” he says. In his opinion, changes are constant, and except for the rapidly increasing cost of living, he doesn’t think the changes are negative.

“Individual businesses come and go, but I don’t see the neighbourhood becoming any less welcoming,” he says. Still, Dutton laments that many seniors on fixed incomes have been leaving the area against their will as rents continue to skyrocket.

As some gay people resist the tide and stay in gay neighbourhoods, many more are undeniably leaving — even as North American cities begin to recognize their cultural and, especially, potential financial value.

The permanent rainbow crosswalks in Vancouver and now in Toronto and the newly installed rainbow LED strip lights in Vancouver are all being used to promote these villages as destinations, to locals and tourists alike. These efforts at urban renewal can also contribute to the gentrification that eventually prices many gays and lesbians out of these areas.

To many, especially to the younger generation, the notion of a single gay district seems antiquated. As gay people, men especially, increasingly turn online to find sexual and romantic connections, their need for gay bars and physical places to meet and hook up diminishes. As the world becomes safer for some sexual minorities, the need for the protective embrace of the gaybourhood also begins to decline. In the early 1990s, there were 16 gay bars in Boston. By 2007, that number had dropped by half.

Ghaziani references these phenomena as part of the “post-gay” era, where gays are being accepted by society and are choosing to assimilate into the mainstream. He says it’s changed the way many of us think about ourselves.

As an example, he points to statistician Nate Silver, who was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in 2009. In a 2012 interview with Out magazine, Silver said that his friends saw him as “sexually gay, but ethnically straight.”

Ghaziani’s book defines “post-gay” partly as an assertion that who a man has sex with “is not necessarily related to his self-identity or to the cultural communities in which he participates.” He compares this sort of sexual identity with white ethnic identity: “optional, episodic and situational.”

In reviewing media interviews with various gay people — often couples — who have chosen not to live in gaybourhoods and who say they are fitting in, he notes that their tones are often laced with some shame. He wonders why the opposite of “blending in” is having a “scarlet letter on our heads” or being “those people?”

“Assimilation into the mainstream is always accompanied by infighting within a minority group, especially between those who are eager to blend in and those who are determined to hold on to what makes them different,” he writes.

Interestingly, Ghaziani’s book also includes interviews from some of the straight people living in gaybourhoods. He finds that many are “benignly indifferent” to their gay neighbours, while a minority feel that they are victims of reverse discrimination.

He found the responses of straight people so repetitive and almost rehearsed that it was hard to tell if they were being honest about being indifferent or if they were just being politically correct. One single, straight 28-year-old in Boystown told Ghaziani that he would like to see the rainbow pylons and flags taken down because, in his opinion, self-segregation was hurting the gay movement politically.

Ghaziani argues that even while many outgrow them, gaybourhoods remain “culturally relevant as refuges for queer youth of colour, transgender individuals and queers who hail from small towns, because antigay bigotry still affects their everyday life.”

Despite having left the confines of Vancouver’s gay village, Ewing agrees that there will always be a need for the gaybourhood, but she stresses the importance of it needing to be about more than just bars. She would like to see more places that include non-drinkers and youth.

Ghaziani suggests that it’s unreasonable to expect gaybourhoods — or any neighbourhood, for that matter — to remain stable and unchanged but that it’s equally unreasonable to declare them dead.

Neighbourhoods often move, reform and migrate, he says. Toronto’s “Queer West” and Vancouver’s Commercial Drive are two such examples. Many young queer people may want to live in a gay area, but they settle where they can afford the rents, even if that means congregating in — and queering — new neighbourhoods.

Ghaziani further theorizes that these gay-friendly neighbourhoods could eventually become full-fledged gay neighbourhoods in their own right. If the old gaybourhood was an island, these new models are archipelagos. These new villages may eventually supersede the older ones, or they may all coexist.

Dutton says that while we have gained a lot of freedom under the law, that doesn’t negate the need for the gaybourhood. “I think there is much to be said for an accepting environment where people can feel free to dress unusually or where they can express their affection for one another openly. That would be regretful if those things were lost over time,” he says.

“I don’t think the times have progressed to the point where we’re all just equal,” he continues. “There is much to be said for having a place within the city where people can come from elsewhere and feel that this is home — this is where my people congregate.”

CHICAGO: People from LGBT community face subtle discrimination even in ‘gaybourhoods’

Prejudice and discrimination still exist- it’s just more subtle and difficult to detect.(Shutterstock)

Straight people living in neighbourhoods mostly populated by LGBT folks say they support gay rights in theory, but their street interactions contradict those sentiments.

Gaybourhood, or traditionally gay neighbourhood, still face a subtle form of discrimination from ‘straight’ people. According to a study conducted by the University of British Columbia, straight people living in such neighbourhoods, say they support gay rights in theory, but many interact with their gay and lesbian next-door fellas on the street in ways that contradict those sentiments. “There is a mistaken belief that marriage equality means the struggle for gay rights is over,” said Amin Ghaziani, the study’s senior author. “Prejudice and discrimination still exist- it’s just more subtle and difficult to detect.”

The researchers interviewed 53 straight people, who live in two Chicago gaybourhoods – Boystown and Andersonville. They found the majority of residents saying that they support gay people. However, the researchers found their progressive attitudes were misaligned with their actions. While many residents said they don’t care if people are gay or straight, some indicated that they don’t like gay people who are “in your face”.

When asked about resistance from LGBTQ communities to the widespread trend of straight people moving into gaybourhoods, some of the people interviewed responded with accusations of reverse discrimination and described gay people who challenged them as “segregationist” and “hetero-phobic.” Some said they believed they should have open access to cultural gay spaces, and were surprised that they felt “unwelcome” there. “That feeling of surprise, however, exemplifies a misguided belief that gay districts are trendy commodities when they are actually safe spaces for sexual minorities”, added Ghaziani.

When the researchers asked residents if they had done anything to show their support of gay rights, such as marching in the pride parade, donating to an LGBTQ organization, or writing a letter in support of marriage equality to a politician, the majority said they had not. Many also expected their gay and lesbian neighbours to be happy and welcoming of straight people moving into gaybourhoods, expressing sentiments like, “you wanted equality- this is what equality looks like.”

With gay pride celebrations fast approaching around the world, Adriana Brodyn, the study’s lead author, said it is important to pause and reflect on the state of LGBTQ equality. “I hope that our research motivates people against becoming politically complacent or apathetic,” she said. “If we do not motivate ourselves to be aware of this subtle form of prejudice, then it will just continue to perpetuate.” The study appears in the journal City and Community.

REYKJAVIK: Where’s The Gaybourhood?

I’ve asked around. Though the sample size is hardly one that would hold up under intense scrutiny, a pattern has begun to emerge. The question “Where’s the gaybourhood?”, when raised in Reykjavík, will most likely be met with the response (after several, strangely long seconds of quiet contemplation): “Well—it’s a very small city.” Whether my interlocutor is heterosexual, or part of the alphabet soup, the answer is the same.

This strikes me as odd for a number of reasons. The first being that, while yes, relative to some far more populous cities of the world—Shanghai, Istanbul, Lagos, São Paulo, New York City, etc. (thanks, Wikipedia!)—Reykjavík’s approximate 120,000 is rather small. Further, this question also deals greatly with historical population growth over time—go back to 1901, and the population was only a bit over 6,300.

But, still… A population of 120,000 seems significant to me—though to be fair, I did grow up in a small-ish town (15,000 in a good year). And I can think of plenty of cities with populations smaller than Reykjavík’s that foster vibrant gay scenes, if not full-fledged gaybourhoods.

And yeah, the development of “gaybourhoods” was historically aided (though not exclusively) by the existence of a highly trafficked urban space with large international shipping ports, naval and military bases and heavy involvement in major wars, as well as a significant history of cosmopolitanism, internal migration and immigration from abroad, and…

Well, I think I just answered my own question, didn’t I? And it’s nothing against Iceland—that’s just not how things worked here. Historically, at least.

I don’t buy that culture is born exclusively as an act of defiance, or out of need for defence, and thus dies out when the need for shielding is gone.

There are a few historical spaces I was able to read up on. Known to those “in the know,” ya know? Informally, and before LGBT+ was even a conceivable acronym. Walking through Reykjavík, I feel as though I’m surrounded by hidden histories. Historical gay spots, as far as I could find, were highly secretive and unofficial, rarely documented, and limited in number and size out of necessity—this wasn’t especially news to me.

What struck me more, as I learned to accept that a lot of what I was looking for in terms of historical narrative would remain in permanent obscurity, was the following: where exactly were the present scenes? I mean, it’s one thing for a “gaybourhood” to not have existed in the past—but where’s the presence now? Why does it appear as though not much new is forming?

It wasn’t long before I started to find various explanations for the lack of gaybourhood, queer scene, or various cultural presence in contemporary Reykjavík via the wonderfully enlightening netherworld of tourist-information websites. One of the more striking quotations I found goes as follows, taken from Guide to Iceland’s website:

As for gay-culture, there isn’t much, because there does not need to be. Gays participate as regular members of society, and in Iceland there are openly gay people in all sectors and levels of society. And as such, there is no gaybourhood…

Forgetting (as much as I’d prefer not to) the use of “gay” in place of a wide variety of different identities and experiences, I wonder how much truth there is to this sentiment. Yes, Iceland is ahead of the curve in many ways in terms of LGBT+ legal rights—impressively so. But legal rights are hardly the same thing as acceptance (which, by the way, is hardly a victory—see the Riddle Scale), and certainly legal rights are not the same thing as actual safety, security, comfort, self-determined expression, etc. I don’t buy that culture is born exclusively as an act of defiance, or out of need for defence, and thus dies out when the need for protection is gone (which, mind you, it certainly is not).

So, to answer my question, the “gaybourhood” as of now exists alongside the straightbourhood (i.e. the World). Reykjavík has the outward appearance of an assimilationist’s utopia—lesbian beside queer beside trans beside intersex beside bisexual beside gay beside straight beside etc., all dancing contentedly in the same small club, no difference between them. Except that there are differences—different experiences, different wants and needs, different discrete identities and worldviews. And there is no way that everyone can or should always exist together like this.

It’s great that all spaces are open to us, and that many (though not all) can feel relatively safe living as ourselves. But no one wants only to co-mingle—with heterosexuals, or with adjacent letters. In speaking to LGBTQ+ persons of Reykjavík (while knowing there are still many more to talk to, and still much, much more to hear), one does seem to detect a want and a need for them to carve out discrete spaces for themselves. Though I wonder how much room here there actually is to do so.

VANCOUVER: ‘Gaybourhoods’ are expanding, not disappearing: UBC study

Sociology professor Amin Ghaziani says as couples diversify, so does where they call home

The corner of Davie Street and Bute Street in Vancouver, B.C. (Wikimedia Commons)

Gay and lesbian spaces, commonly known as “gaybourhoods,” are expanding across cities, rather than disappearing, a new B.C. study says.

Gaybourhoods, such as Vancouver’s Davie Village, are nothing new. A common perception has been that major cities have just one neighbourhood where all gay people live.

But new research by University of British Columbia sociology professor Amin Ghaziani, released Thursday, shows that members of the LGBTQ community are diversifying where they live, choosing what he calls “cultural archipelagos” beyond the gaybourhood. Only 12 per cent of LGBTQ adults live in a gaybourhood, while 72 per cent have never.

Ghaziani used data from the 2010 U.S. census to track location patterns of lesbians, transgender people, same-sex couples with children, and LGBTQ people of color.

He found queer communities of colour have emerged in Chicago and the outer boroughs of New York. That’s because African-American people in same-sex relationships are more likely to live in areas where there are higher populations of other African-Americans, rather than other LGBTQ people, he found.

Rural areas draw more same-sex female couples than male couples, and female couples tend to live where the median housing price per square foot is lower, which Ghaziani attributed to a possible reflection of the gender pay gap.

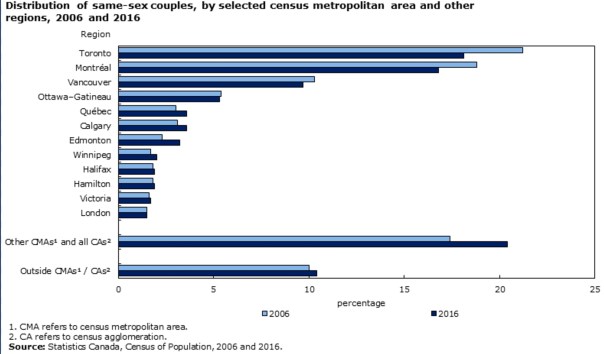

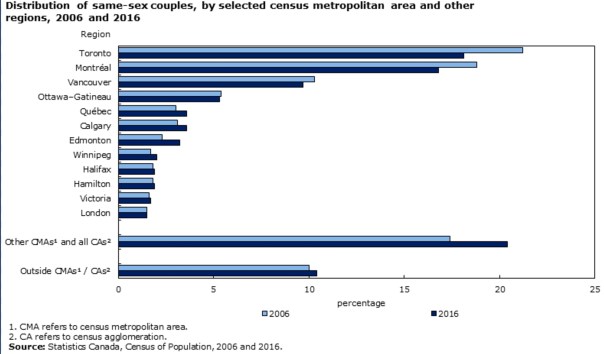

The study focuses on the U.S., but the findings are similar to data released in the last Canadian census.

There were 73,000 same-sex couples in the country in 2016, an increase of more than half over the last decade.

Meanwhile, major cities that were historically popular for same-sex couples, such as Toronto and Montreal, saw a nearly five per cent dip in the same time period, while areas such as Victoria are seeing an increase.

CANADA: Same-sex marriages rise, as gaybourhoods change

There were nearly 73,000 same-sex couples in 2016 in Canada, about a 61 per cent increase

The number of same-sex couples in Canada increased by more than half in the last decade, with three times more couples choosing to get married, census data shows.

There were nearly 73,000 same-sex couples in 2016 – about a 61 per cent increase from the 43,000 reported in the 2011 census.

The increase in the number of reported same-sex couples could be due to attitudes liberalizing dramatically since gay marriage was approved in 2005 in Canada and 2013 in the U.S., according to Amin Ghaziani, Canada Research Chair in Sexuality and Urban Studies at the University of British Columbia.

New census data shows a rapid increase in same-sex couples tying the knot – with one-third of couples reportedly being married – including Vancouver-area residents Laura and Jen O’Connor.

The pair got married for all the romantic, fairy-tale reasons: after seven years together, they were deeply in love and wanted to start a family. But on another level, they thought it might just make their life together a little easier.

After all, being gay comes with its own unique set of challenges – challenges they hoped might be easier to navigate if they shared a last name.

“It’s one less thing, one less obstacle that you have to deal with,” says Jen, 27, during an interview in a sun-drenched backyard at Laura’s parents’ house in Cloverdale.

They decided to move in to save money after spending $15,000 on three unsuccessful rounds of in vitro fertilization.

The pair are currently saving up to buy a home of their own in the Vancouver area – the third-most popular metropolitan city for same-sex couples to live in across the country, behind Toronto and Montreal.

Gaybourhoods are nothing new, including Vancouver’s Davie Street – a well-known destination for LGBTQ members in B.C., but are seemingly becoming less of the hotspots they once were, according to Ghaziani.

“Acceptance produces more of a dispersion,” he said, adding that cultural and social factors work hand-in-hand with the economics of where same-sex couples and singles look to live.

Acceptance is only one factor in the decision-making process, though, as real estate prices remain high and unaffordable for many, especially those with children.

Lesbians are considered the trailblazers of LGBTQ migration, Ghaziani said, historically finding trendy neighbourhoods that are progressive, cheaper and have nearby sustainable resources like grocery and book stores.

Due to the gender wage gap and 80 per cent of same-sex couples with kids being female, lesbians are usually the first to be pushed out of neighbourhoods once late-stage gentrification begins, he said.

For example, as Davies Street tends to offer single occupancy units at higher rent – leaving the one-eighth of same-sex couples with children most likely looking to more affordable non-urban areas.

And as more traditional gaybourhoods change, others seem to be beginning in other parts of the province. More than 1,200 same-sex couples resided in Victoria in 2016, according to the census data, compared to about 700 in 2006.

With files from Laura Kane from The Canadian Press

AUSTRALIA: Australia’s biggest ‘Gaybourhoods ‘

Australia’s “gaybourhoods” are rapidly changing and relocating. We took a look at some of the most prominent LGBTI locales with the help of Australian Census data on same-sex couples.

1. Potts Point (NSW)

Gone are the days Darlinghurst held the crown as Sydney’s queer capital. While the Oxford Street strip still hosts Sydney’s annual Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade, a few suburbs over to the east of the CBD you’ll find the beating heart of the city’s LGBTI culture in Potts Point. In the 2011 Australian Census, Potts Point had the second-highest concentration of male same-sex couples in capital city suburbs, only .1 of a percentage point off the then leader (Darlinghurst).

Potts Point in Sydney (Greg Wood/AFP/Getty Images).

2. Daylesford (Victoria)

Home to Australia’s largest rural LGBTI festival, ChillOut, Daylesford is a couple of hours outside of Melbourne and is known for its many mineral springs. It’s a popular spot for visitors and mature same-sex couples looking to settle down and invest in a tree-change. People in same-sex couples tend to be more mobile than people in opposite-sex couples. In 2011, 63 per cent of people in same-sex couples lived somewhere else five years ago compared with 40 per cent of people in opposite-sex couples.

A world record attempt at the largest ever simultaneous massage in the popular Victorian spa town of Daylesford in 2010. (Scott Barbour/Getty Images)

3. New Farm (Queensland)

Found in the inner suburbs of Brisbane alongside its winding river, New Farm plays host to the annual Brisbane Pride Festival and is close to the gay nightlife of Fortitude Valley. Brisbane had more than 3500 self-identifying same-sex couples in the 2011 Census, many of whom call New Farm’s leafy streets home.

New Farm Park in Brisbane (Photo by Glenn Hunt/Getty Images)

4. Brunswick (Victoria)

Brunswick isn’t just a hipster hotspot, it’s home to a great many LGBTI people who’ve traded Prahran’s Chapel Street for the northern suburbs of Melbourne. Its culinary and nightlife options have blossomed as Prahran’s famous Commercial Road strip has dwindled in recent years. It also has a higher proportion of female same-sex couples than its southern rival.

Brunswick, Victoria (Mat Connolley/Wiki Commons).

5. Newtown/Erskineville (NSW)

The Newtown/Erskineville area in Sydney’s Inner West is home to the majority of the nation’s female same-sex couples. In fact, if you were to take in the neighbouring suburbs of St Peters and Enmore, you’d account for a whopping 22.4 per cent of female same-sex couples as a percentage of Australia’s capital cities. Its famous terraces and pocket bars also account for 11 per cent of male same-sex couples.

Cyclists along King St, Newtown (Mark Kolbe/Getty Images)

LONDON: London’s hottest Gaybourhoods

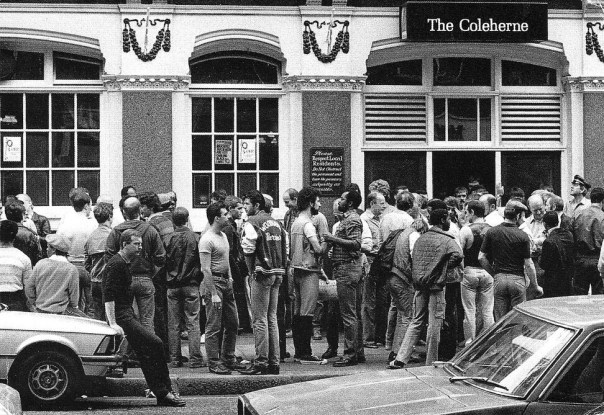

SOHO

Revitalised by the gay community “two or three recessions ago”, according to Coote, but now thoroughly commercialised and “de-gayed”, in the words of photographer Adrian Lourie. Still home to a large collection of clubs and pubs, of course — the Admiral Duncan, Shadow Lounge, G-A-Y — and therefore still a mecca for tourists and out-of-towners. The lesbian Candy Bar closed last year but new bar She Soho is “quite seismic in that it’s the first lesbian bar actually on Old Compton Street”, according to Sophie Wilkinson, news editor of The Debrief.

VAUXHALL

Hot in Vo-zhawl: the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in the heart of SE11 (Pic: Adrian Lourie) ( Adrian Lourie )

The Royal Vauxhall Tavern has been a welcoming destination for gays since the Second World War, and the adjoining Pleasure Gardens contain a popular canoodling hummock more recently dubbed Brokeback Mountain. Vauxhall — formerly VoHo, now Vo-challe or Vo-zhawl — is now home to a sizeable residential community and a massive nightlife scene based around the clubs, bars and saunas under the railway arches: Barcode, Chariots, Fire etc… Possibly on the turn thanks to rising rents. “Going through Vauxhall recently I saw that a gay specialist leather shop had become a halal butcher’s, which is probably the sort of thing that would keep Mr Farage awake at night,” says Ben Summerskill.

HAMPSTEAD

Historically a gay area due to the Heath (before mobile apps made hook-ups easier) and the men’s bathing pond, it’s still beloved of older, wealthier, boho gay residents as well as younger blow-ins or those forced to settle for nearby Kilburn. “It has an upmarket village feel — in a non-Village People way — with a fine housing stock and plentiful high street,” says TV journalist Stefan Levy. There’s also a venerable gay pub, the King William IV (the Willy).

CLAPHAM

As with Hampstead Heath, above, so with Clapham Common: plus, The Two Brewers nightclub and Kazbar remain pivotal venues on the London gay scene. Gays smitten by the “Vale of Cla’am” and able to get on the property ladder there have stayed amid the rising tide of yummy mummies.

SHOREDITCH

A prime example of pioneering gays subsumed within a wider influx of cool, followed by commercialism. The Joiners Arms was a totemic gay venue when Shoreditch felt like “the middle of nowhere” (Summerskill). Then came the Young British Artists, the hipsters, the pop-ups, the City boys and the big chains. Still an LGBT favourite, though, thanks to a thriving art/design and alternative bar/club scene (Sink the Pink nights, etc), though high rents mean gays and lesbians are more likely to settle in Dalston or Hackney (see below). Sophie Wilkinson says Shoreditch is “one of the few pockets of London where I feel I can walk hand in hand with another woman without fear of attack”, along with Soho, Waterloo and Dalston (there are infrequent lesbian club nights at Dalston Superstore).

STOKE NEWINGTON

Home to a sizeable London lesbian community, with social life focused on the nearby parks and the iconic Blush bar on Cazenove Road. Stoke Newington School pioneered the teaching of LGBT History month.

BERMONDSEY

A mixture of Vauxhall and Shoreditch, minus the club culture (though XXL, the club for “bears, cubs and their admirers”, is a short lollop away). It’s near the river but with a large amount of ex-council accommodation and do-up-able warehouse space, plus a burgeoning foodie culture.

CHISWICK

Google “gay Chiswick” and the only result is a car park recommended on a cruising website. But anecdotal reports suggest that many gay air crew — those who can afford it — settle in Chiswick due to its combination of bucolic charm and proximity to Heathrow. One resident claims a W4 postcode is an asset when chatting someone up.

And finally…

PECKHAM

“Definitely the next place!” according to Lourie. His view is echoed by QX magazine, which notes the area’s multicultural vibrancy and arty/student scene fed by Goldsmiths and Camberwell, as well as the queer night Garçonne at the Bussey Building and live art nights at The Flying Dutchman, plus LGBT-friendly bars. Wilkinson also mentions Tooting and Nunhead as potential hotspots as all young creative/club types — not just LGBTQ+ ones — are priced out of central north, west and east London. The next gaybourhood? Look south…

References