The saddest thing about the Potala is that it is devoid of its spiritual head, the Dalai Lama. There is something desolate about lines of tourists and pilgrims circumnavigating the massive, empty complex. One can only hope that, given time, His Holiness will return, and give life back to this icon.

Namaste.

POTALA PALACE

Potala Palace in simplified Chinese (top), traditional Chinese (middle) and Tibetan (bottom).

The Potala Palace (Tibetan: ཕོ་བྲང་པོ་ཏ་ལ་, Wylie: pho brang Potala) inLhasa,Tibet AutonomousRegion,China was the residence of theDalaiLama until the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India during the1959 Tibetan Uprising. It is now a museum and World Heritage Site

The palace is named afterMount , the mythical abode of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara. The 5th Dalai Lama started its construction in 1645 after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (died 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa. It may overlay the remains of an earlier fortress called the White or Red Palace on the site, built by Songtsen Gampon 637.

The building measures 400 metres east-west and 350 metres north-south, with sloping stone walls averaging 3 m. thick, and 5 m. (more than 16 ft) thick at the base, and with copper poured into the foundations to help proof it against earthquakes. Thirteen stories of buildings—containing over 1,000 rooms, 10,000 shrines and about 200,000 statues—soar 117 metres (384 ft) on top of Marpo Ri, the “Red Hill”, rising more than 300 m (about 1,000 ft) in total above the valley floor.

Tradition has it that the three main hills of Lhasa represent the “Three Protectors of Tibet”. Chokpon, just to the south of the Potala, is the soul-mountain (Wylie: bla ri) of Vajrapani , Pongwari that of Manjushri, and Marpori, the hill on which the Potala stands, represents Avalokiteśvara.

The walls of the Red Palace

The site on which the Potala Palace rises is built over a palace erected by Songtsen Gampo on the Red Hill. The Potala contains two chapels on its northwest corner that conserve parts of the original building. One is the Phakpa Lhakhang, the other the Chogyel Drupuk, a recessed cavern identified as Songtsen Gampo’s meditation cave. Lozang Gyatso, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, started the construction of the modern Potala Palace in 1645. The external structure was built in 3 years, while the interior, together with its furnishings, took 45 years to complete. The Dalai Lama and his government moved into the Potrang Karpo (‘White Palace’) in 1649. Construction lasted until 1694, some twelve years after his death. The Potala was used as a winter palace by the Dalai Lama from that time. The Potrang Marpo (‘Red Palace’) was added between 1690 and 1694.

The new palace got its name from a hill on Cape Comorin (Kanyakumari) att the southern tip of India—a rocky point sacred to the bodhisattva of compassion, who is known as Avalokiteśvara, or Chenrezi. The Tibetans themselves rarely speak of the sacred place as the “Potala”, but rather as “Peak Potala” (Tse Potala), or most commonly as “the Peak”.

The palace was slightly damaged during the Tibetan uprising against the Chinese in 1959, when Chinese shells were launched into the palace’s windows. Before Chamdo Jampa Kalden was shot and taken prisoner by soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army, he witnessed “Chinese cannon shells began landing on Norbulingka past midnight on March 19th, 1959… The sky lit up as the Chinese shells hit the Chakpori Medical College and the Potala.” It also escaped damage during the Cultural Revolution in 1966 through the personal intervention of Zhou Enlai who was then the Premier of the People’s Republic of China. Tibetan activist Tsering Woeser claims that the palace, which harboured “over 100,000 volumes of scriptures and historical documents” and “many store rooms for housing precious objects, handicrafts, paintings, wall hangings, statues, and ancient armour”, “was almost robbed empty.”On the other hand, tibetologist Amy Heller writes that “the invaluable library and artistic treasures accumulated over the centuries in the Potala have been preserved.”

The Potala Palace was inscribed to the UNRSCO World Heritage List in 1994. In 2000 and 2001Jokhang Temple and Norbulingka were added to the list as extensions to the sites. Rapid modernisation has been a concern for UNESCO, however, which expressed concern over the building of modern structures immediately around the palace which threaten the palace’s unique atmosphere.[18] The Chinese government responded by enacting a rule barring the building of any structure taller than 21 metres in the area. UNESCO was also concerned over the materials used during the restoration of the palace, which commenced in 2002 at a cost of RMB180 million (US$22.5 million), although the palace’s director, Qiangba Gesang, has clarified that only traditional materials and craftsmanship were used. The palace has also received restoration works between 1989 and 1994, costing RMB55 million (US$6.875 million).

The number of visitors to the palace was restricted to 1,600 a day, with opening hours reduced to six hours daily to avoid over-crowding from 1 May 2003. The palace was receiving an average of 1,500 a day prior to the introduction of the quota, sometimes peaking to over 5,000 in one day.[19] Visits to the structure’s roof were banned after restoration efforts were completed in 2006 to avoid further structural damage.[20] Visitorship quotas were raised to 2,300 daily to accommodate a 30% increase in visitorship since the opening of the Quinsang railway into Lhasa on 1 July 2006, but the quota is often reached by midmorning . Opening hours were extended during the peak period in the months of July to September, where over 6,000 visitors would descend on the site.

The former quarters of the Dalai Lama. The figure in the throne represents Tenzin Gyatso,The incumbent Dalai Lama

Built at an altitude of 3,700 m (12,100 ft), on the side of Marpo Ri (‘Red Mountain’) in the center of Lhasa Valley,[23] the Potala Palace, with its vast inward-sloping walls broken only in the upper parts by straight rows of many windows, and its flat roofs at various levels, is not unlike a fortress in appearance. At the south base of the rock is a large space enclosed by walls and gates, with gold porticos on the inner side. A series of tolerably easy staircases, broken by intervals of gentle ascent, leads to the summit of the rock. The whole width of this is occupied by the palace.

The central part of this group of buildings rises in a vast quadrangular mass above its satellites to a great height, terminating in gilt canopies similar to those on the Jokhang. This central member of Potala is called the “red palace” from its crimson colour, which distinguishes it from the rest. It contains the principal halls and chapels and shrines of past Dalai Lamas. There is in these much rich decorative painting, with jewelled work, carving and other ornamentation.

The Chinese Putuo Zongchen Temple, UNESCO World Heritage Site, built between 1767 and 1771, was in part modeled after the Potala Palace. The palace was named by the American television show Good Morning America and newspaper USA Today as one of the “New Seven Wonders”.

The Leh Palace in Leh, Ladakh, India is also modelled after the Potala Palace.

The Lhasa Zhol Pillars

Lhasa Zhol Village has two stone pillars or rdo-rings, an interior stone pillar or doring nangma, which stands within the village fortification walls, and the exterior stone pillar or doring chima, which originally stood outside the South entrance to the village. Today the pillar stands neglected to the East of the Liberation Square, on the South side of Beijing Avenue.

The doring chima dates as far back as c. 764, “or only a little later”, and is inscribed with what may be the oldest known example of Tibetan writing.

The creation of the Tibetan script is traditionally attributed to Thonmi Sambhota who is said to have been sent to India early in the reign of Songsten Gampo where he devised an alphabet suitable for the Tibetan language by adapting elements of Indian scripts.

The pillar was erected during the reign of the early Tibetan emperor, Trisong Detsen (755 until 797 or 804 CE) in the village of Zhol (which has disappeared because of recent construction), which stood just before the Potala Palace. It was commissioned by the powerful minister Nganlam Takdra Lukhong, generally considered an opponent of Buddhism.

The inscription starts off by announcing that Nganlam Takdra Lukhong had been appointed Great Inner Minister and Great Yo-gal ‘chos-pa (a title difficult to translate). It goes on to say that Klu-khong brought to Trisong Detsen the facts of the murder of his father, Me Agtsom (704-754) by two of his Great Ministers, ‘Bal Ldong-tsab and LangMyes-zigs, and that they intended to harm him also. They were then condemned and Klu-kong was appointed Inner Minister of the Royal Council.

It then gives an account of his services to the king including campaigns against Tang China which culminated in the brief capture of the Chinese capital Chang’an (modern Xi’an) in 763 CE during which the Tibetans temporarily installed as Emperor a relative of Princess Jincheng Gongzhu (Kim-sheng Kong co), the Chinese wife of Trisong Detsen’s father, Me Agtsom.

It is a testament to the generally tolerant attitude of Tibetan culture that this proud memorial by a subject was allowed to stand after the re-establishment of Buddhism under Trisong Detsen and has survived until modern times.

The pillar contains dedications to a famous Tibetan general and gives an account of his services to the king including campaigns against China which culminated in the brief capture of the Chinese capital Chang’an (modern Xian) in 763 during which the Tibetans temporarily installed as Emperor a relative of Princess Jincheng Gongzhu (Kim-sheng Kong co), the Chinese wife of Trisong Detsen’s father, Me Agtsom.

Traditionally among the celebrations for Tibetan New Year, or Losar, a team of sportsmen, usually from Shigatse, would perform daredevil feats such as sliding down a rope from the top of the highest roof of the Potala, to the Zhol Pillar at the foot of the hill. However, the 13th Dalai Lama banned this performance because it was dangerous and sometimes even fatal.

As of 1993 the pillar was fenced off so it could not be approached closely (see accompanying photo).

Potala adorned with two Buddhist silk banners, Koku, (gos sku) for the Sertreng ceremony (tshogs mchod ser spreng) with the Shol Doring (pillar) is in the foreground in 1949

The Lhasa Zhol pillars in 1993.

NORBULINGKA

(Standard Tibetan: ནོར་བུ་གླིང་ཀ་; Wylie: Nor-bu-gling-ka; simplified Chinese: 罗布林卡; traditional Chinese: 羅布林卡; literally “The Jewelled Park”) is a palace and surrounding park in Lhasa, Tibet, China, built from 1755. It served as the traditional summer residence of the successive Dalai Lamas from the 1780s up until the 14th Dalai Lama’s exile in 1959. Part of the “Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace”, Norbulingka is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and was added as an extension of this Historic Ensemble in 2001. It was built by the 7th Dalai Lama and served both as administrative centre and religious centre. It is a unique representation of Tibetan palace architecture.

Norbulingka Palace is situated in the west side of Lhasa, a short distance to the southwest of Potala Palace. Norbulingka covers an area of around 36 hectares (89 acres) and considered to be the largest man made garden in Tibet.

Norbulingka park is considered the premier park of all such horticultural parks in similar ethnic settings in Tibet. During the summer and autumn months, the parks in Tibet, including the Norbulinga, become hubs of entertainment with dancing, singing, music and festivities. The park is where the annual Sho Dun or ‘Yoghurt Festival’ is held.

The Norbulingka palace has been mostly identified with the 13th and the 14th Dalai Lamas who commissioned most of the structures seen here now. During the invasion of Tibet in 1950, a number of buildings were damaged, but were rebuilt beginning in 2003, when the Chinese government initiated renovation works here to restore some of the damaged structures, and also the greenery, the flower gardens and the lakes.

In Tibetan, Norbulingka means “Treasure Garden.” or Treasure Park”. The word ‘Lingka’ is commonly used in Tibet to define all horticultural parks in Lhasa and other cities. When the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, Norbulingka was renamed People’s Park and opened to the public.

The palace, with 374 rooms, is located 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) west of the Potala Palace, which was the winter palace. It is in the western suburb of Lhasa City on the bank of the Kyichu River. When construction of the palace was started (during the 7th Dalai Lama’s period) in the 1740s, the site was a barren land, overgrown with weeds and scrub and infested with wild animals.

The park, situated at an elevation of 3,650 metres (11,980 ft) had flower gardens of roses, petunias, hollyhocks, marigolds, chrysanthemums and rows of herbs in pots and rare plants. Fruit trees including apple, peach and apricot were also reported (but the fruits did not ripen in Lhasa), and also poplar trees and bamboo. In its heyday, the Norbulingka grounds were also home to wildlife in the form of peacocks and brahminy ducks in the lakes. The park was so large and well-laid-out, that cycling around the area was even permitted to enjoy the beauty of the environment. The gardens are a favourite picnic spot, and provide a beautiful venue for theatre, dancing and festivals, particularly the Shodun or ‘Yoghurt Festival’, which is at the beginning of August, with families camping in the grounds for days, surrounded by colourful makeshift windbreaks of rugs and scarves and enjoying the height of summer weather.

There is also a zoo at Norbulingka, originally to house the animals which were given to the Dalai Lamas. Heinrich Harrer helped the 14th Dalai Lama build a small movie theatre there in the 1950s.

Norbulingka Palace of the Dalai Lamas was built about 100 years after the Potala Palace was built on the Parkori peak, over a 36 hectares (89 acres) land area. It was built a little away to the west of the Potala for the exclusive use by the Dalai Lama to stay in during the summer months. Tenzing Gyatso, the present 14th Dalai Lama, stayed here before he fled to India. The building of the palace and the park was undertaken by the 7th Dalai Lama from 1755. The Norbulingka Park and Summer Palace were completed in 1783 under Jampel Gyatso, the 8th Dalai Lama, on the outskirts of Lhasa. and became the summer residence during the reign of the Eighth Dalai Lama.

The earliest history of Norbulingka is traced originally to a spring at this location, which was used during the summer months by the 7th Dalai Lama to cure his health problems. Qing Dynasty permitted the Dalai Lama to build a palace at this location for his stay, as a resting pavilion. Since subsequent Dalai Lamas also used to stay here for their studies (before enthronement) and as a summer resort, Norbulingka came to be known as the Summer Palace of the Dalai LamaThe 8th Dalai Lama was responsible for many additions to the Norbulingka complex in the form of palaces and gardens.

However, it is sometimes reported that 6th 5(4@through to 12th Dalai Lamas died young and under mysterious circumstances, conjectured as having been poisoned. Most of the credit for the expansion of Norbulingka is given to the 13th and the 14th Dalai Lamas.

It was from the Norbulingka palace that the Dalai Lama escaped to India on 17 March 1959, under the strong belief that he would be captured by the Chinese. On this day, the Dalai Lama dressed like an ordinary Tibetan, and, carrying a rifle across his shoulder, left the Norbulinga palace and Tibet to seek asylum in India. As there was a dust storm blowing at that time, he was not recognized. According to Reuters, “The Dalai Lama and his officials, who had also escaped from the palace, rode out of the city on horses to join his family for the trek to India”. The Chinese discovered this “great escape” only two days later. The party journeyed through the Himalayas for two weeks, and finally crossed the Indian border where they received political asylum. Norbulingka was later surrounded by protesters and subject to an attack by the Chinese.

The summer residence of the Dalai Lama, located in the Norbulingka Park, is now a tourist attraction. The palace has a large collection of Italian chandeliers, Ajanta frescoes, Tibetan carpets, and many other artifacts. Murals of Buddha and the 5th Dalai Lama are seen in some rooms. The 14th Dalai Lama’s (who fled from Tibet and took asylum in India) meditation room, bedroom, conference room and bathroom are part of the display and are explained to tourists.

Built in the 18th century, the Norbulingka Palace and the garden within its precincts have undergone several additions over the years. The vast complex covers a garden area of 3.6 km2 including 3.4 km2 of lush green pasture land covered with forests. It is said to be the “highest garden” anywhere in the world and has earned the epithet “Plateau Oxygen Bar.”

The Norbulingka is the “world’s highest, largest and best-preserved ancient artificial horticultural garden”., which also blends gardening with architecture and sculpture arts from several Tibetan ethnic groups; 30,000 cultural relics of ancient Tibetan history are preserved here. The complex is demarcated under five distinct sections. A cluster of buildings to the left of the entrance gate is the Kelsang Phodang (The full name of this palace is “bskal bzang bde skyid pho brang”), named after the 7th Dalai Lama, Kelsang Gyatso (1708–1757). It is a three-storied palace with chambers for the worship of Buddha, bedrooms, reading rooms and shelters at the centre. The Khamsum Zilnon, a two-storied pavilion, is opposite the entry gate. The 8th Dalai Lama, Jamphel Gyatso (1758–1804) substantially enlarged the palace by adding three temples and the perimeter walls on the south east sector and the park also came to life with plantation of fruit trees and evergreens brought from various parts of Tibet. The garden was well developed with a large retinue of gardeners. To the northwest of Kelsang Phodrong is the Tsokyil Phodrong, which is a pavilion in the midst of a lake and the Chensil Phodrong. On the west side of Norbulingka is the Golden Phodron, built by a benefactor in 1922, and a cluster of buildings which were built during the 13th Dalai Lama’s time. The 13th Dalai Lama was responsible for architectural modifications, including the large red doors to the palace; he also improved the Chensel Lingkha garden to the northwest. To the north of Tsokyil Phodrong is the Takten Migyur Phodrong which was built in 1954 by 14th Dalai Lama and is the most elegant palace in the complex, a fusion of a temple and villa. The new summer palace, which faces south, was built with Central Government funds, and completed in 1956.

The earliest building is the Kelsang Palace built by the Seventh Dalai Lama which is “a beautiful example of Yellow Hat architecture. Dalai Lamas watched, from the first floor of this palace, the folk operas held opposite to the Khamsum Zilnon during the Shoton festival. Its fully restored throne room is also of interest.”

The Norbulingka ’s most dramatic area was the Lake Palace, built in the southwest area. In the centre of the lake, three islands were connected to the land by short bridges. A palace was built on each island. A horse stable and a row of four houses contained the gifts received by the Dalai Lamas from the Chinese emperors and other foreign dignitaries.

Construction of the ‘New Palace’ was begun in 1954 by the present Dalai Lama, and completed in 1956. It is a double-story structure with a Tibetan flat roof. It has an elaborate layout with a maze of rooms and halls. This modern complex contains chapels, gardens, fountains and pools. It is a modern Tibetan-style building embellished with ornamentation and facilities. In the first floor of this building, there are 301 paintings (frescoes) on Tibetan history, dated to the time when Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama met Chairman Mao Zedong As of 1986, the palace had an antique Russian radio, and a Philips console still containing old 78 rpm records.

The entire Norbulingka complex was delimited by two sets of walls. The area encompassed by the inner wall, painted yellow, was exclusively for the use of the Dalai Lama and his attendants. Officials and the Dalai Lama’s royal family lived in the area between the inner yellow wall and the outer wall. A dress code was followed for visitors to enter the palace; those wearing Tibetan dress were allowed; guards posted at the gates controlled the entry, and ensured that no western hat-wearing people (which was made popular in Tibet during Lhamdo Dhondups time) were allowed inside. Wearing shoes inside the park was banned. Guards at the gate offered a formal arms salute to the nobles and high-ranking officials. Even the officials at the lower category also received a salute. The gates outside the yellow wall were heavily protected. Only the Dalai Lama and his guardians could pass through these gates. Tibetan mastiff dogs kept in niches of the compound walls, and tied with long yak hair leashes, were the guard dogs that patrolled the perimeter of the Norbulingka.

On the east gate to the Norbulingka there are two Snow Lion statues covered in khatas (thin white scarves offered as a mark of respect), the Snow Lion on the left is accompanied by a lion cub. The mythical Snow Lion is the symbol of Tibet; according to legend they jump from one snow peak to another. Most of the buildings are closed now; have become storehouses or used as offices for those who take care of the maintenance works. Some additional buildings seen now are souvenir kiosks catering to the visitors.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Norbulingka complex suffered extensive damage. However, in 2001, the Central Committee of the Chinese Government in its 4th Tibet Session resolved to restore the complex to its original glory. Grant funds to the extent of 67.4 million Yuan (US$8.14 million) were sanctioned in 2002 by the Central Government for restoration work; restoration work beginning in 2003 mainly covered the Kelsang Phodron Palace, the Kashak Cabinet offices and many other structures.

Norbulingka was declared a “National Important Cultural Relic Unit”, in 1988 by the State council. On 14 December 2001, UNESCO inscribed it as a World Heritage Site as part of the “Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace”.The historic ensemble covers three monuments namely, the Potala Palace, winter palace of the Dalai Lama, the Jokhang Temple Monastery and the Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s former summer palace built in the 18th century considered a masterpiece of Tibetan art. The citation states: “preservation of vestiges of the traditional Tibetan architecture”. This is viewed in the context of extensive modern development that has taken place under Chinese suzerainty in Tibet. The Chinese State Tourism Administration has also categorized Norbulingka at a “Grade 4 A at the National Tourism (spot) level,” in 2001. It was also declared a public park in 1959.

Takten Migyur Potrang

Tyokyil Potrang

Norbulingka Shoton Festival

Beautiful Norbulingka Park

JOKHANG TEMPLE MONASTERY

Plan of the complex from Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet by Sarat Chandra Das, 1902

The Jokhang (Tibetan: ཇོ་ཁང།, Chinese: 大昭寺), also known as the Qoikang Monastery, Jokang, Jokhang Temple, Jokhang Monastery and Zuglagkang (Tibetan: གཙུག་ལག་ཁང༌།, Wylie: gtsug-lag-khang, ZYPY: Zuglagkang or Tsuklakang), is a Buddhist temple in Barkhor Square in Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet. Tibetans, in general, consider this temple as the most sacred and important temple in Tibet. The temple is currently maintained by the Gelug school, but they accept worshipers from all sects of Buddhism. The temple’s architectural style is a mixture of Indian vihara design, Tibetan and Nepalese design.

The Jokhang was founded during the reign of King Songtsen Gampo. According to tradition, the temple was built for the king’s two brides: Princess Wencheng of the Chinese Tang dynasty and Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal. Both are said to have brought important Buddhist statues and images from China and Nepal to Tibet, which were housed here, as part of their dowries. The oldest part of the temple was built in 652. Over the next 900 years, the temple was enlarged several times with the last renovation done in 1610 by the Fifth Dalai Lama. Following the death of Gampo, the image in Ramcho Lake temple was moved to the Jokhang temple for security reasons. When King Tresang Detsen ruled from 755 to 797, the Buddha image of the Jokhang temple was hidden, as the king’s minister was hostile to the spread of Buddhism in Tibet. During the late ninth and early tenth centuries, the Jokhang and Ramoche temples were said to have been used as stables. In 1049 Atisha, a renowned teacher of Buddhism from Bengal taught in Jokhang.

Around the 14th century, the temple was associated with the Vajrasana in India. In the 18th century the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty, following the Gorkha-Tibetan war in 1792, did not allow the Nepalese to visit this temple and it became an exclusive place of worship for the Tibetans. During the Chinese development of Lhasa, the Barkhor Square in front of the temple was encroached. During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards attacked the Jokhang temple in 1966 and for a decade there was no worship. Renovation of the Jokhang took place from 1972 to 1980. In 2000, the Jokhang became a UNESCO World Heritage Site as an extension of the Potala Palace (a World Heritage Site since 1994). Many Nepalese artists have worked on the temple’s design and construction.

The temple, considered the “spiritual heart of the city” and the most sacred in Tibet, is at the centre of an ancient network of Buddhist temples in Lhasa. It is the focal point of commercial activity in the city, with a maze of streets radiating from it. The Jokhang is 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) east of the Potala Palace. Barkhor, the market square in central Lhasa, has a walkway for pilgrims to walk around the temple (which takes about 20 minutes). Barkhor Square is marked by four stone sankang (incense burners), two of which are in front of the temple and two in the rear.

Jokhang Temple interior building

Rasa Thrulnag Tsuklakang (“House of Mysteries” or “House of Religious Science”) was the Jokhang’s ancient name. When King Songtsen built the temple his capital city was known as Rasa (“Goats”), since goats were used to move earth during its construction. After the king’s death, Rasa became known as Lhasa (Place of the Gods); the temple was called Jokhang—”Temple of the Lord”—derived from Jowo Shakyamuni Buddha, its primary image. The Jokhnag’s Chinese name is Dazhao; it is also known as Zuglagkang, Qoikang Monastery, Tsuglakhang and Tsuglhakhange.

Tibetans viewed their country as a living entity controlled by srin ma (pronounced “sinma”), a wild demoness who opposed the propagation of Buddhism in the country. To thwart her evil intentions, King Songtsen Gampo (the first king of a unified Tibet) developed a plan to build twelve temples across the country. The temples were built in three stages. In the first stage central Tibet was covered with four temples, known as the “four horns” (ru bzhi). Four more temples, (mtha’dul), were built in the outer areas in the second stage; the last four, the yang’dul, were built on the country’s frontiers. The Jokhang temple was finally built in the heart of the srin ma, ensuring her subjugation.

To forge ties with neighbouring Nepal, Songtsen Gampo sent envoys to King Amsuvarman seeking his daughter’s hand in marriage and the king accepted. His daughter, Bhrikuti, came to Tibet as the king’s Nepalese wife (tritsun; belsa in Tibetan). The image of Akshobhya Buddha, which she had brought as part of her dowry, was deified in a temple in the middle of a lake known as Ramoche.

Gampo, wishing to obtain a second wife from China, sent his ambassador to Emperor Taizong (627–650) of the Tang dynasty for one of his daughters. Taizong rejected the king’s proposal, considering Tibetans “barbarians”, and announced the marriage of one of his daughters to the king of Duyu, a Hun. This infuriated Gampo, who mounted attacks on tribal areas affiliated with the Tang dynasty and then attacked the Tang city of Songzhou. Telling the emperor that he would escalate his aggression unless the emperor agreed to his proposal, Gampo sent a conciliatory gift of a gold-studded “suit of armour” with another request for marriage. Taizong conceded, giving Princess Wencheng to the Tibetan king. When Wencheng went to Tibet in 640 as the Chinese wife of the king (known as Gyasa in Tibet), she brought an image of Sakyamuni Buddha as a young prince. The image was deified in a temple originally named Trulnang, which became the Jokhang. The temple became the holiest shrine in Tibet and the image, known as Jowo Rinpoche, has become the country’s most-revered idol.

The oldest part of the temple was built in 652 by Songtsen Gampo. To find a location for the temple, the king reportedly tossed his hat (a ring in another version) ahead of him with a promise to build a temple where the hat landed. It landed in a lake, where a white stupa (memorial monument) suddenly emerged over which the temple was built. In another version of the legend, Queen Bhrikuti founded the temple to install the statue she had brought and Queen Wencheng selected the site according to Chinese geomancy and feng shui. The lake was filled, leaving a small pond now visible as a well fed by the ancient lake, and a temple was built on the filled area. Over the next nine centuries, the temple was enlarged; its last renovation was carried out in 1610 by the Fifth Dalai Lama.

The temple’s design and construction are attributed to Nepalese craftsmen. After Songtsen Gampo’s death, Queen Wencheng reportedly moved the statue of Jowo from the Ramoche temple to the Jokhang temple to secure it from Chinese attack. The part of the temple known as the Chapel was the hiding place of the Jowo Sakyamuni.

During the reign of King Tresang Detsan from 755 to 797, Buddhists were persecuted because the king’s minister, Marshang Zongbagyi (a devotee of Bon), was hostile to Buddhism. During this time the image of Akshobya Buddha in the Jokhang temple was hidden underground, reportedly 200 people failed to locate it. The images in the Jokhang and Ramoche temples were moved to Jizong in Ngari, and the monks were persecuted and driven from Jokhang. During the anti-Buddhist activity of the late ninth and early tenth centuries, the Jokhang and Ramoche temples were said to be used as stables. In 1049 Atisha, a renowned teacher of Buddhism from Bengal who taught in Jokhang and died in 1054, found the “Royal Testament of the Pillar” (Bka’ chems ka khol ma) in a pillar at Jokhang; the document was said to be the testament of Songtsen Gampo.

Life-sized Statue of Shykamuni

Beginning in about the 14th century, the temple was associated with the Vajrasana in India. It is said that the image of Buddha deified in the Jokhang is the 12-year-old Buddha earlier located in the Bodh Gaya Temple in India, indicating “historical and ritual” links between India and Tibet. Tibetans call Jokhang the “Vajrasana of Tibet” (Bod yul gyi rDo rje gdani), the “second Vajrasana” (rDo rje gdan pal} and “Vajrasan, the navel of the land of snow” (Gangs can sa yi lte ba rDo rje gdani).

After the occupation of Nepal by the Gorkhas in 1769, during the Gorkha-Tibetan war in 1792 the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty drove the Gorkhas from Tibet and the Tibetans were isolated from their neighbors. The period, lasting for more than a century, has been called “the Dark Age of Tibet”. Pilgrimages outside the country were forbidden for Tibetans, and the Qianlong Emperor suggested that it would be equally effective to worship the Jowo Buddha at the Jokhang.

In Chinese development of Lhasa, Barkhor Square was encroached when the walkway around the temple was destroyed. An inner walkway was converted into a plaza, leaving only a short walkway as a pilgrimage route. In the square, religious objects related to the pilgrimage are sold.

During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards attacked the Jokhang in 1966 and for a decade there was no worship in Tibetan monasteries. Renovation of the Jokhang began in 1972, and was mostly complete by 1980. After this and the end of persecution, the temple was re-consecrated. It is now visited by a large number of Tibetans, who come to worship Jowo in the temple’s inner sanctum. During the Revolution, the temple was spared destruction and was reportedly boarded up until 1979. At that time, portions of the Jokhang reportedly housed pigs, a slaughterhouse and Chinese army barracks. Soldiers burned historic Tibetan scriptures. For a time, it was a hotel.

Two flagstone doring (inscribed pillars) outside the temple, flanking its north and south entrances, are worshiped by Tibetans. The first monument, a March 1794 edict known as the “Forever Following Tablet” in Chinese, records advice on hygiene to prevent smallpox; some has been chiseled out by Tibetans who believed that the stone itself had curative powers. The second, far older, pillar is 5.5 metres (18 ft) high with a crown in the shape of a palace and an inscription dated 821 or 822. The tablet has a number of names; “Number One Tablet in Asia”, “Lhasa Alliance Tablet”, “Changing Alliance Tablet”, “Uncle and Nephew Alliance Tablet” and the “Tang Dynasty-Tubo Peace Alliance Tablet”. Its inscription, in Tibetan and Chinese, is a treaty between the Tibetan king Ralpacan and the Chinese emperor Muzong delineating the boundary between their countries. Both inscriptions were enclosed by brick walls when Barkhor Square was developed in 1985. The Sino-Tibetan treaty reads, “Tibet and China shall abide by the frontiers of which they are now in occupation. All to the east is the country of Great China; and all to the west is, without question, the country of Great Tibet. Henceforth on neither side shall there be waging of war nor seizing of territory. If any person incurs suspicion he shall be arrested; his business shall be inquired into and he shall be escorted back”.

According to the Dalai Lama, among the many images in the temple was an image of Chenrizi, made of clay in the temple, within which the small wooden statue of the Buddha brought from Nepal was hidden. The image was in the temple for 1300 years, and when Songtsen Gampo died his soul was believed to have entered the small wooden statue. During the Cultural Revolution, the clay image was smashed and the smaller Buddha was given by a Tibetan to the Dalai Lama.

In 2000, the Jokhang became a UNESCO World Heritage Site as an extension of the Potala Palace (a World Heritage Site since 1994) to facilitate conservation efforts. The temple is listed in the first group of State Cultural Protection Relic Units, and has been categorized as a 4A-level tourist site.

Pilgrims prostrating before entering the Johkang Temple, Lhasa, Tibet

On February 17, 2018, the temple caught fire at 6:40 p.m. (local time), before sunset in Lhasa, with the blaze lasting until late that evening. Although photos and videos about the fire were spread on Chinese social media, which showed the eaved roof of a section of the building lit with roaring yellow flames and emitting a haze of smoke, these images were quickly censored and disappeared. The official newspaper Tibet Daily briefly claimed online that the fire was “quickly extinguished” with “no deaths or injuries” at the late night, while The People’s Daily published the same words online and added that there had been “no damage to relics” in the temple; both of these reports contained no photos. The temple was temporarily closed after the fire but were reopened to public on February 18, according to official Xinhua news agency. But the yellow draperies had been newly hung behind the temple’s central image, the Jowo statue. And no one was allowed to enter the second floor of the temple, according to the source of Radio Free Asia’s Tibetan Service. The fire burned an area of about 50 square meters. The temple’s golden cupola had been removed to guard against any collapse and protective supports had been added around the Jowo statue, according to Xinhua On February 19, 2018, the Dalai Lama’s supporters based in India reported eyewitness accounts that “the source of the fire is not the Jowo chapel but from an adjacent chapel within the Jokhang temple premises known in Tibetan as Tsuglakhang” and confirming that there were “no casualties and damage to property is yet to be ascertained”.

The Jokhang temple covers an area of 2.51 hectares (6.2 acres). When it was built during the seventh century, it had eight rooms on two floors to house scriptures and sculptures of the Buddha. The temple had brick-lined floors, columns and door frames and carvings made of wood. During the Tubo period, there was conflict between followers of Buddhism and the indigenous Bon religion. Changes in dynastic rule affected the Jokhang Monastery; after 1409, during the Ming dynasty, many improvements were made to the temple. The second and third floors of the Buddha Hall and the annex buildings were built during the 11th century. The main hall is the four-story Buddha Hall.

The temple has an east-west orientation, facing Nepal to the west in honour of Princess Bhrikuti. Additionally, the monastery’s main gate faces west. The Jokhang is aligned along an axis, beginning with an arch gate and followed by the Buddha Hall, an enclosed passage, a cloister, atriums and a hostel for the lamas (monks). Inside the entrance are four “Guardian Kings” (Chokyong), two on each side. The main shrine is on the ground floor. On the first floor are murals, residences for the monks and a private room for the Dalai Lama, and there are residences for the monks and chapels on all four sides of the shrine. The temple is made of wood and stone. Its architecture features the Tibetan Buddhist style, with influences from China, Indian vihara design and Nepal. The roof is covered with gilded bronze tiles, figurines and decorated pavilions

The central Buddha Hall is tall, with a large, paved courtyard. A porch leads to the open courtyard, which is two concentric circles with two temples: one in the outer circle and another in the inner circle. The outer circle has a circular path, with a number of large prayer wheels (nangkhor); this path leads to the main shrine, which is surrounded by chapels. Only one of the temple murals remains, depicting the arrival of Queen Wencheng and an image of the Buddha. The image, brought by the king’s Nepalese wife and initially kept at Ramoche, was moved to Jokhang and kept in the rear center of the inner temple. This Buddha has remained on a platform since the eighth century; on a number of occasions, it was moved for safekeeping. The image, amidst those of the king and his two consorts, has been gilded several times. In the main hall on the ground floor is a gilded bronze statue of Jowo Sakyamuni, 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) tall, representing the Buddha at age twelve. The image has a bejewelled crown, cover around its shoulder, a diamond on its forehead and wears a pearl-studded garment. The Buddha is seated in a lotus position on a three-tiered lotus throne, with his left hand on his lap and his right hand touching the earth. A number of chapels surround the Jowo Sakayamuni, dedicated to gods and bodhisattvas. The most important bodhisattva here is the Avalokiteshwara, the patron saint of Tibet, with a thousand eyes and a thousand arms. Flanking the main hall are halls for Amitabha (the Buddha of the past) and Qamba (the Buddha of the future). Incarnations of Sakyamuni are enshrined on either side of a central axis, and the Buddha’s warrior guard is in the middle of the halls on the left side.

In addition to the main hall and its adjoining halls, on both sides of the Buddha Hall are dozens of 20-square-metre (220 sq ft) chapels. The Prince of Dharma chapel is on the third floor, including sculptures of Songtsen Gampo, Princess Wencheng, Princess Bhrikuti, Gar Tongtsan (the Tabo minister) and Thonmi Sambhota, the inventor of Tibetan script. The halls are surrounded by enclosed walkways.

Decorations of winged apsaras, human and animal figurines, flowers and grasses are carved on the superstructure. Images of sphinxes with a variety of expressions are carved below the roof.

The temple complex has more than 3,000 images of the Buddha and other deities (including an 85-foot (26 m) image of the Buddha)[9] and historical figures, in addition to manuscripts and other objects. The temple walls are decorated with religious and historical murals.

On the rooftop and roof ridges are iconic statues of golden deer flanking a Dharma wheel, victory flags and monstrous fish. The temple interior is a dark labyrinth of chapels, illuminated by votive candles and filled with incense. Although portions of the temple has been rebuilt, original elements remain. The wooden beams and rafters have been shown by carbon dating to be original, and the Newari door frames, columns and finials dating to the seventh and eighth centuries were brought from the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal.

In addition to walking around the temple and spinning prayer wheels, pilgrims prostrate themselves before approaching the main deity; some crawl a considerable distance to the main shrine. The prayer chanted during this worship is “Om mani padme hum” (Hail to the jewel in the lotus). Pilgrims queue on both sides of the platform to place a ceremonial scarf (katak) around the Buddha’s neck or touch the image’s knee. A walled enclosure in front of the Jokhang, near the Tang Dynasty-Tubo Peace Alliance Tablet, contains the stump of a willow known as the “Tang Dynstay Willow” or the “Princess Willow”. The willow was reportedly planted by Princess Wencheng.

The Jokhang has a sizeable, significant collection of cultural artefacts, including Tang-dynasty bronze sculptures and finely-sculpted figures in different shapes from the Ming dynasty. Among hundreds of thangkas, two notable paintings of Chakrasamvara and Yamanataka date to the reign of the Yongle Emperor; both are embroidered on silk and well-preserved. The collection also has 54 boxes of Tripiṭaka printed in red, 108 carved sandalwood boxes with sutras and a vase (a gift from the Qianlong Emperor) used to select the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama.

“SYDNEY MORNING HERALD

FEARS FOR ANCIENT TIBETAN JOKHANG TEMPLE AFTER FIRE

By KIRSTY NEEDHAM

18 February 2018 — 3:47pm

The most important Tibetan pilgrimage site, the Jokhang Temple in old Lhasa, was ablaze on Saturday night but few details have been released by the Chinese government about the extent of the damage.

The 7th Century Tibetan building, which sprawls over 2.5 hectares, is protected by law and is listed for its “outstanding universal value” by the United Nations cultural protection agency, UNESCO.

Jokhang Monastery, one of the oldest Tibetan monastery in Lhasa, western China’s Tibet province, in 2007.

Photo: AP

London-based Tibetan expert Robert Barnett told Fairfax Media: “The Jokhang is widely regarded as the most sacred site in Tibetan Buddhism, with thousands of pilgrims travelling across the plateau for centuries to reach there and still doing so today, when allowed to.”

“It was the earliest Buddhist temple to be built in Tibet and is seen by many Tibetans as the symbolic heart of the country and of its cultural heritage.”

A UNESCO report in 2016 stated the temple was in a good state of conservation but noted fire was a “high disaster risk” and prevention measures were in place.

After multiple videos of the large fire in Lhasa’s old town, in which Tibetans can be heard gasping and crying, spread on social media on Saturday night, Chinese state media confirmed there had been “a partial fire in the Jokhang Temple. The fire was quickly extinguished and no casualties reported”.

Dharma wheel on Jokhang Temple.

Photo: Alamy

The fire had broken out at 6.40pm, and the Communist Party secretary for the district, Wu Yingjie, had “rushed to the scene”, the official Tibet Daily reported on its social media account.

Barnett, author of Lhasa: Streets with Memories, dismissed later reports by some people on social media that the Jokhang Temple was not affected.

“This kind of confusion reflects the control on information in Tibet, where there is extremely limited official news as well as constant campaigns threatening people who ‘spread rumours’, meaning anything seen by the authorities as supporting the Dalai Lama and ‘hostile forces’ or as potentially leading to unrest,” he said.

While the fire may have started in the adjoining Meru Nyingpa on the Barkor Circuit, it had spread to the eastern part of the main Jokhang Temple, and could be seen on the video, he said.

“The extent of the damage remains unclear.”

The news agency Xinhua was among the Chinese official media outlets reporting the fire, and said the Jokhang Temple was “renowned” for Tibetan Buddhism and had a “history of more than 1300 years and houses many cultural treasures, including a life-sized statue of Sakyamuni when he was 12 years old”.

According to UNESCO reports, the hall surrounded by accommodation for monks on four sides was constructed of wood and stone, and housed more than 3000 images of Buddha and other deities, as well as treasures and manuscripts. Its murals depicted historical scenes.

Tibetan scholars said official information about the fire was limited, raising concerns about damage. Access to the temple area was said to have been restricted.

Tibetans had celebrated the start of the Losar Tibetan New Year on Friday.

Xinhua reported on Sunday afternoon that the Barkhor square around the temple had reopened to the public after a closure caused by the fire.

The Jokhang Temple would be closed from Monday to Thursday in a “scheduled” closure, Xinhua said.”

View Potala Palace from Jokhang Temple

Devouted Pilgrim in front of Barkhor Temple

* A note on Dhvaja (flags or banners)

These are not how Westerners perceive flags to be.

Dhvaja (Victory banner) – pole design with silk scarfs, on the background the Potala Palace

Kosigrim at English Wikipedia • Public domain

Dhvaja (Skt. also Dhwaja; Tibetan: རྒྱལ་མཚན, Wylie: rgyal-msthan), meaning banner or flag, is composed of the Ashtamangala, the “eight auspicious symbols.”Dhvaja in Hindu or vedic tradition takes on the appearance of a high column (dhvaja-stambha) erected in front of temples. Dhvaja, meaning a flag banner, was a military standard of ancient Indian warfare. Notable flags, belonging to the Gods, are as follows:

▪ Garuda Dhwaja – The flag of Vishnu.

▪ Indra Dhwaja – The flag of Indra. Also a festival of Indra.

▪ Kakkai kodi – The flag of Jyestha, goddess of inauspicious things and misfortune.

▪ Kapi Dhwaja or Vanara dwaja (monkey flag) – The flag of Arjuna in the Mahabharata, in which the Lord Hanuman himself resided

▪ Makaradhvaja – The flag of Kama, god of love.

▪ Seval Kodi – The war flag of Lord Murugan, god of war. It depicts the rooster, Krichi.

Dhvaja (‘victory banner’), on the roof of Jokhang Monastery.

Within the Tibetan tradition a list of eleven different forms of the victory banner is given to represent eleven specific methods for overcoming “defilements” (Sanskrit: klesha). Many variations of the dhvaja’s design can be seen on the roofs of Tibetan monasteries (Gompa, Vihara) to symbolyze the Buddha’s victory over four maras.

In its most traditional form the victory banner is fashioned as a cylindrical ensign mounted upon a long wooden axel-pole. The top of the banner takes the form of a small white “parasol” (Sanskrit: chhatra), which is surrounded by a central “wish granting gem” (Sanskrit: cintamani). This domed parasol is rimmed by an ornate golden crest-bar or moon-crest with makara-trailed ends, from which hangs a billowing yellow or “white silk scarf'”(Sanskrit: khata) (see top right).

Dhvaja (‘victory banner’), on the roof of Sanga Monastery.

As a hand-held ensign the victory banner is an attribute of many deities, particularly those associated with wealth and power, such as Vaiśravaṇa, the Great Guardian King of the north. As roof-mounted ensign the victory banners are cylinders usually made of beaten copper (similar to toreutics) and are traditionally placed on the four corners of monastery and temple roofs. Those roof ornaments usually take the form of a small circular parasol surmounted by the wish-fulfilling gem, with four or eight makara heads at the parasol edge, supporting little silver bells (see the Jokhang Dhvaja on the left). A smaller victory banner fashioned on a beaten copper frame, hung with black silk, and surmounted by a flaming “trident” (Sanskrit: trishula) is also commonly displayed on roofs (see the dhvaja on the roof of the Potala Palace below.

References

▪ Bass, Catriona. 1990. Inside the Treasure House: A Time in Tibet. Victor Gollancz, London. Paperback reprint: Rupa & Co., India, 1993

▪ Dowman, Keith. 1988. The Power-places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim’s Guide. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London and New York. ISBN 0-7102-1370-0

▪ Palin, Michael (2009). Himalaya. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7538-1990-6.

▪ Seth, Vikram (1990). From Heaven Lake: Travels through Sinkiang and Tibet. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-013919-2.

▪ Tibet: A Fascinating Look at the Roof of the World, Its People and Culture. Passport Books. 1988. p. 71.

▪ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Lhasa”. Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 529–532. (See p. 530.)

▪Beckwith, Christopher I. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 0-691-02469-3.

▪ “Reading the Potala”. Peter Bishop. In: Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places In Tibetan Culture: A Collection of Essays. (1999) Edited by Toni Huber, pp. 367–388. The Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, H.P., India. ISBN 81-86470-22-0.

▪ Das, Sarat Chandra. Lhasa and Central Tibet. (1902). Edited by W. W. Rockhill. Reprint: Mehra Offset Press, Delhi (1988), pp. 145–146; 166-169; 262-263 and illustration opposite p. 154.

▪ Larsen and Sinding-Larsen (2001). The Lhasa Atlas: Traditional Tibetan Architecture and Landscape, Knud Larsen and Amund Sinding-Larsen. Shambhala Books, Boston. ISBN 1-57062-867-X.

▪Richardson, Hugh E. (1984) Tibet & Its History. 1st edition 1962. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. Shambhala Publications. Boston ISBN 0-87773-376-7.

▪ Richardson, Hugh E. (1985). A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions. Royal Asiatic Society. ISBN 0-94759300-4.

▪ Snellgrove, David & Hugh Richardson. (1995). A Cultural History of Tibet. 1st edition 1968. 1995 edition with new material. Shambhala. Boston & London. ISBN 1-57062-102-0.

▪ von Schroeder, Ulrich. (1981). Indo-Tibetan Bronzes. (608 pages, 1244 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-01-8

▪ von Schroeder, Ulrich. (2001). Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Vol. One: India & Nepal; Vol. Two: Tibet & China. (Volume One: 655 pages with 766 illustrations; Volume Two: 675 pages with 987 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-07-7

▪ von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2008. 108 Buddhist Statues in Tibet. (212 p., 112 colour illustrations) (DVD with 527 digital photographs). Chicago: Serindia Publications. ISBN 962-7049-08-5

▪ An, Caidan (2003). Tibet China: Travel Guide. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 978-7-5085-0374-5.

▪ Barnett, Robert (2010). Lhasa: Streets with Memories. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13681-5.

▪ Barron, Richard (10 February 2003). The Autobiography of Jamgon Kongtrul: A Gem of Many Colors. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 978-1-55939-970-8.

▪ Brockman, Norbert C. (13 September 2011). Encyclopedia of Sacred Places. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-655-3.

▪ Buckley, Michael (2012). Tibet. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-382-5.

▪ Dalton, Robert H. (2004). Sacred Places of the World: A Religious Journey Across the Globe. Abhishek. ISBN 978-81-8247-051-4.

▪ Davidson, Linda Kay; Gitlitz, David Martin (2002). Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland : an Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-004-8.

▪ Dorje, Gyurme (2010). Jokhang: Tibet’s Most Sacred Buddhist Temple. Edition Hansjorg Mayer. ISBN 978-5-00-097692-0.

▪ Huber, Toni (15 September 2008). The Holy Land Reborn: Pilgrimage and the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-35650-1.

▪ Jabb, Lama (10 June 2015). Oral and Literary Continuities in Modern Tibetan Literature: The Inescapable Nation. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-0334-1.

▪ Klimczuk, Stephen; Warner, Gerald (2009). Secret Places, Hidden Sanctuaries: Uncovering Mysterious Sites, Symbols, and Societies. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4027-6207-9.

▪ Laird, Thomas (10 October 2007). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-4327-3.

▪ Mayhew, Bradley; Kelly, Robert; Bellezza, John Vincent (2008). Tibet. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-569-7.

▪ McCue, Gary (1 March 2011). Trekking Tibet. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-1-59485-411-8.

▪ Perkins, Dorothy (19 November 2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-93569-6.

▪ Powers, John (25 December 2007). Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 978-1-55939-835-0.

▪ Representatives, Australia. Parliament. House of (1994). Parliamentary Debates Australia: House of Representatives. Commonwealth Government Printer.

▪ Service, United States. Foreign Broadcast Information (1983). Daily Report: People’s Republic of China. National Technical Information Service.

▪ von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2001. Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Vol. One: India & Nepal; Vol. Two: Tibet & China. (Volume One: 655 pages with 766 illustrations; Volume Two: 675 pages with 987 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-07-7

▪ von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2008. 108 Buddhist Statues in Tibet. (212 p., 112 colour illustrations) (DVD with 527 digital photographs mostly of Jokhang Bronzes). Chicago: Serindia Publications. ISBN 962-7049-08-5

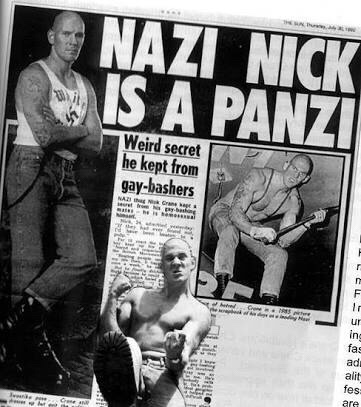

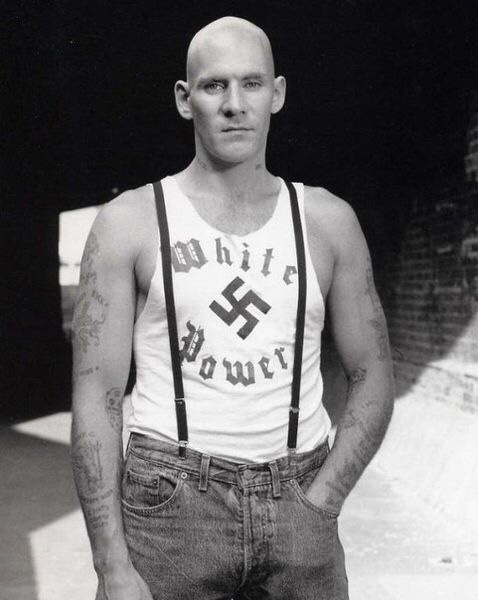

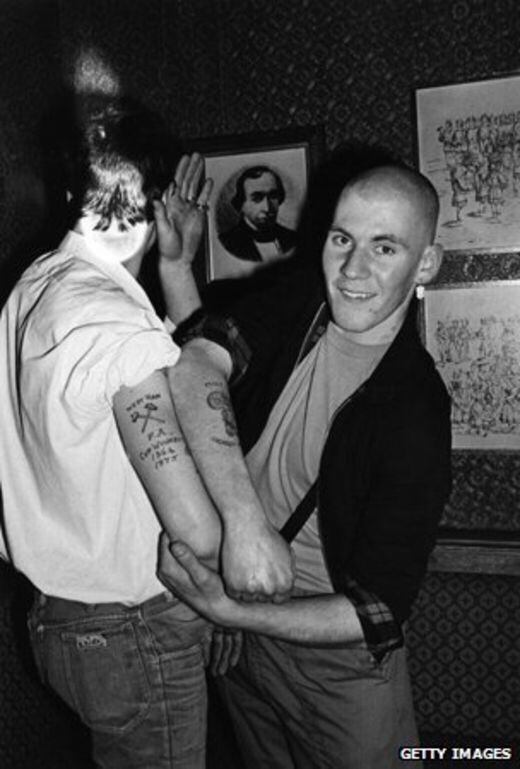

A young Crane shows off his tattoos with another skinhead

A young Crane shows off his tattoos with another skinhead