Hell Division: Pentridge Prison’s section for the baddest and maddest

It is pretty trendy now – the development that was once Pentridge Prison.

You wonder if the customers at the coffee shop just outside the imposing bluestone walls know or care about the brutality that went on for decades in what was Victoria’s biggest jail.

Down the bottom end was H Division, reserved for the baddest, the maddest and sometimes the meekest (it was used for protection as well as punishment).

As part of the redevelopment of the prime real estate the old labour yards were recently demolished – pens open to the weather where inmates broke rocks until 1976.

The place was rebuilt so often it did not resemble the original design and the developers have promised to rebuild a section to the original 19th-century specs.

The days of breaking rocks are long gone and anyone who still advocates “old-style” brutal punishment for inmates has rocks in their head.

If animals at the Melbourne Zoo were kept in such conditions there would have been mass protests but few ever saw what went on down in Hell Division.

New inmates learnt the first lesson on the way in. It was known as the “Liquorice Mile”, where prison officers formed a guard of honour reception to beat prisoners (often naked) to the point of submission.

When Building Society bandit Greg “Doc” Smith arrived he was advised by standover man Mark “Chopper” Read to walk slowly and keep his head up to show hecould take the beating.

Strangely, both inmates became best-selling authors. Smith, also known as Gregory David Roberts, escaped and was recaptured 10 years later. His autobiographical novel Shantaram became a runaway success, much like “Doc” himself.

Another who used the suffering to create was Ray Mooney, now an acclaimed playwright.

But many who ended up there were beyond redemption or the barbaric conditions made them so. It was the chicken and egg argument – leaving most of them either stuffed or scrambled.

It was here in 1958 that police killer William O’Meally became the last man flogged with the cat-o’-nine-tails as a punishment.

Back in 1990 I went to H Division to interview long-term inmate “Chopper” Read after he complained about a critical profile I had written about him.

It was certainly nothing like the movies with a glass screen and a telephone link. We sat in a small room at the end of the division separated by a cheap table.

Read chatted and I took notes. The subsequent story amused many but not the Parole Board, which delayed his release for another six months.

A violent world

The first impression inside the bluestone and concrete complex was the sense of cold. When it rained in winter the damp would get into your bones and stay there for months.

It was bleak. A place of rape, drugs, despair and overwhelming hopelessness. To make it less grim they white washed the walls, built a swimming pool and introduced contact visits.

During one such visit an man jailed for armed robbery took the opportunity to punch his mother in the face, breaking her nose. So much for humanitarianism.

During the famed Overcoat Gang War inmates were bashed and stabbed with home-made shivs. A razor blade buried in a soap bar would slice open an inmate in the showers. Cells doors were left open to facilitate beatings of non-favoured inmates.

With no video the attacks followed a pattern. The offender would stab his victim and then cut his own hands to make it look as if he had been attacked – then plead self defence.

In most cases it worked.

One prison officer who worked there said, “It was very heavy but there were rules. They could fight among themselves but if they touched a prison officer they got hell for 48 hours.”

There are few left in the system who served time at H and they remain among the most notorious in Australia. One was an old murderer who came out of retirement to become a contract killer in the Melbourne underworld war. He was caught, proving that hitmen, boxers and country and western singers should never make comebacks.

There is Paul Steven Haigh, who had killed six people, including a nine-year-old boy, before he turned 22.

“It takes no hero to murder. The most puny man in the world can pull a trigger. The obstacle is a psychological one,” he told me inside Pentridge.

In 1991, he helped kill fellow prisoner Donald George Hatherley. Haigh assisted Hatherley to hang himself inside his cell by hanging on to his dangling legs.

But this was no mercy killing. Prison officers say he was miffed that, after Julian Knight killed seven people in Hoddle Street in 1987, he was no longer Victoria’s most prolific killer. And so he needed another victim to break even.

Pentridge staff say Haigh had a Grim Reaper costume delivered to the jail, which he intended to wear to his trial. He was told he could wear a bad brown suit like every other crook.

He is now serving six life sentences, plus 15 years for the Hatherley murder and a further 15 for armed robberies. So much for fancy dress.

Knight was another to spend time in H and was a polarising figure. Russell Street bomber Craig Minogue was a mate whereas other equally violent men hated his guts.

Minogue was a strong ally and a bad enemy. He disliked businessman-turned-killer Alex Tsakmakis and in 1988 caved his head in with a pillow case filled with weights, proving that not all exercise is good for you.

The former H officer said Tsakmakis and Peter David McEvoy, one of the men accused and acquitted of the 1988 killing of constables Steven Tynan and Damian Eyre in Walsh Street, were the worst. “They were both pure evil.”

In 1993 prison authorities discovered an escape plot involving up to 30 H Division inmates.

They found one prisoner’s diary that detailed a plan to free the 30 inmates from their cells and then attack Knight.

The four alleged ringleaders were the best escape artists in the system but the plan was foiled when the division was locked down after a prison officer was stabbed 17 times with a pair of tailor’s scissors.

The investigation found locks cut with a hacksaw blade and a fake prison officer’s uniform hidden in a cell.

It was the beginning of the end for H Division. The hard heads were slowly transferred to the new Barwon maximum-security jail and Pentridge was closed three years later.

One of the hard heads was Badness – Christopher Dean Binse. As one of Australia’s most prolific escape artists he was sent to H Division and still remains in maximum security.

Binse has spent most of his adult life in jail. He was declared a ward of the state at 13, transferred to Pentridge at 17 and moved to H Division at 18. He has tried to escape eight times and has succeeded in both Melbourne and Sydney.

Never one to believe that crooks should keep a low profile he took out a classified ad in the Herald Sun to declare “Badness is back”. He paid with stick-up money.

He bought a Queensland country property with the proceeds of bank jobs and called it “Badlands” and had personalised number plates – “Badness”.

His last arrest was after a 2012 East Keilor siege that ended after 44 hours when he was shot repeatedly by Special Operations Group police using a beanbag shot. He survived and was sentenced to another long prison stint.

Possibly the hardest of his generation was Gregory John “Bluey” Brazel now a convicted triple killer who in 1991 held a prison officer hostage during a siege by holding a knife to his throat for three hours.

Convicted 78 times he has proved to be as bad inside as outside of prison.

His jail record shows there is no chance of him changing. He has stabbed three prisoners, broken the noses of two prison officers, assaulted police, set fire to his cell, cut the tip off his left ear, threatened to kill staff, smashed a governor’s head through a plate-glass window and threatened witnesses using a jail telephone.

One prison officer said Brazel was beaten after he punched a prison officer. “He sooked all afternoon but didn’t complain. He was good as gold the next day.”

He also went on a protracted hunger strike that he cancelled only when it was discovered he was surviving on a stash of Mars Bars hidden in his cell.

But in prison there is the law of the jungle. The toughest get old and are replaced by the new bad boys.

Bluey Brazel was eventually severely beaten by Matthew “The General” Johnson, who went on to murder Carl Williams in Barwon Prison much the way Minogue killed Tsakmakis years earlier.

And so the cycle of death continues.

We have more than 6000 prisoners in the system. Nearly all will one day get out. Although it is human nature to want revenge we have to make sure jails don’t just nurture violence. Not for them but for us.

‘Nightmare like and unreal’: the letter from Pentridge

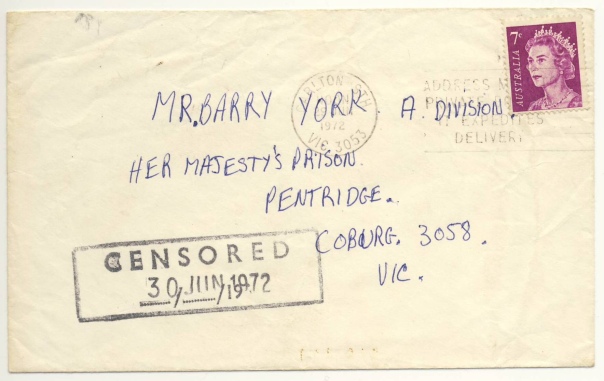

The following letter was smuggled out of Pentridge Prison in July 1972 by Barry York, when he was imprisoned in the ‘A’ Division.

A preamble – Barry York

The letter was written secretly in my cell in ‘A’ Division when I was a prisoner in Pentridge Gaol with two comrades, Brian Pola and Fergus Robinson. There was no shortage of time to write it, as we were in solitary confinement, in our separate cells, for sixteen hours each day.

In writing the letter, I was careful not to be detected by the screws. They would have been very angry about it. So, I hid it under my mattress, folding the letter narrowly so that I could hide it under the side of the mattress nearest to the wall. One day, the warders came in to do a cell inspection. They did the usual finger across the top of the door checking for dust, and then checked that the blankets were folded into perfect squares and then – to my horror – they decided to check under the mattress. They pushed it up from the bed frame but not far enough, so my letter was still hidden at the side of the bed nearest to the wall. I was very worried, I can tell you.

I forget how the letter was smuggled out – possibly by Ted Hill, chairman of the CPA(ML), on one of his visits as our ‘legal adviser’. I recall that Ted used to smuggle the newspaper Vanguard into the gaol by rolling it up and putting it under his trouser leg. He would then give it to me, during a ‘legal visit’, and I’d do the same and carry it in my sock and trouser leg to ‘A’ Division.

Vanguard, the newspaper of the Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist), published the letter on 17 August 1972, after we were released (on 4 August). They knew not to publish it while we were still inside. Thank heavens.

We were gaoled for contempt of the Supreme Court of Victoria in 1972.

We had been leaders of the militant student movement at La Trobe University and prohibited from entering the campus under an injunction taken out by the University authorities. We defied the injunction, seeing it as an encroachment on free speech and an attempt to quell campus militancy. For ‘stepping foot upon the premises known as La Trobe University’, we were gaoled without trial, without sentence (i.e., indefinitely), without rights of bail or appeal.

Fergus was captured first and did four months. Brian Pola next, did three months. I was caught last, and served six weeks. Rodney Taylor, the fourth named in the injunction, avoided capture. We were released when the University authorities surrendered to the mass campaign against the gaolings and approached the Supreme Court for the abandonment of the injunctions.

*

When I read my letter today – forty-five years on – I stand by its description of prison life. However, I would moderate some of my language. For instance, I wouldn’t refer to the gaol as a concentration camp; though technically it was similar. But, ‘concentration camp’ brings to mind the Nazi rule of terror in Germany in the 1930s and Pentridge was nothing like that. (Did I even have to say that?)

Also, the analysis that concluded that ‘all prisoners are political prisoners’ because they were victims of the class war was manifestly wrong. There was, and is, a big difference between people who are imprisoned for their political activities or beliefs and those who rob banks and steal cars. I’m not sure now why I would have gone along with that anarchist slogan. I identified as a communist, after all.

*In 1973, Fergus and Brian and I, and others, revived the Victorian Prisoners’ Action Committee (PAC). I became its spokesman for three or four years. The PAC fought for prison reform but tried to connect the issue to the bigger question of capitalism and its overthrow. We supported the rebellion that was taking place inside Pentridge and other gaols, led by inmates with whom we had become friendly, and perhaps influenced, on the inside. (We used to hide works by Marx, Lenin and Mao on the very top of the bookcase in the prison library, laying them flat and out of view of the prison officers. We were able to receive such books from the outside, after a La Trobe academic comrade assured the prison authorities they were ‘for educational purposes’! Sympathetic prisoners knew of this secret stash of subversive material that was allowed in only for the ‘La Trobe Three’).

In campaigning for prison reform, we were able to assist individuals on their release. This experience was double-edged, and some negative experiences led me to better understand that there is such a thing as personal responsibility and agency, not just victimhood. Even the most oppressed individuals can make choices for the better within the confines of socio-economic limitation. Too many didn’t. Bad culture perpetuates oppression.

*This year, I came across the letter as published in Vanguard while sorting and culling folders of old paperwork. It reminded me of how genuine we were in our commitment to revolutionary change back then, and how lucky I was to have been active in those years of global solidarity from 1967 to 1972. We really believed we were approaching a revolutionary situation. Perhaps the State had similar feelings, and that may explain why they came down so heavily on those who went beyond reformism and challenged the system itself.

Of course, the revolution didn’t materialise but the broader social movement, of which we were part, won changes that cannot be reversed.

And, perhaps best of all: we certainly gave some bad reactionaries a very hard time!

The letter from Pentridge, July 1972

As I write this letter from my cell in ‘A’ Division, two very significant occurrences are taking place.

Firstly a radio announcement from the Prison Committee’s prisoners’ representative has called for prisoners in remand to submit affidavits to Mr. Kelly, a solicitor on the Government Prison Inquiry, regarding a vicious attack by about 30 screws (N.B. prison slang for warders) on 4 Bendigo escapees and about 6 other prisoners. Pentridge is buzzing with the news. The escapees, according to eye witness reports, were beaten with 3 ft. long night sticks. Apparently, one had his head forced through a railing on a staircase. The scalp split wide open and he lost much blood.

Other prisoners in remand who objected to the screws’ violent attack were also bashed. One of the prisoners who received a bashing has identified [name removed] not only as one of those most active in the baton attack, but also as one who laid in the boot after some of the prisoners were beaten unconscious!! The escapees, still without medical aid, have been placed in Pentridge’s ‘maximum security’ division, ‘H’ Division.

HELL DIVISION

‘H’ Division stands for ‘Hell’ Division. And this leads me to the second significant occurrence taking place as I write.

From his cell in ‘H’, Paul Hertzell [correct spelling is Hetzel] is screaming out the following statement:–

‘Hey all you toffs (N.B. prison slang for ‘good blokes’) out there! You’re doing a terrific job! We’ve got to get rid of this incompetent government!’, ‘Down with the imperial government!’, ‘This is Paul Hertzell in ‘H’. All ‘H’ prisoners are political prisoners – a result of the government’s incompetency!’, ‘Free all political prisoners!’, ‘Abolish ‘H’!’, ‘Hey you toffs out there! This is Paul Hertzell in ‘H’…’

I have an almost uncontrollable urge to climb up to my window and scream back my complete support, but unfortunately, I lack the courage of Paul Hertzell. Confronted in an isolated prison cell by overpowering violence, Hertzell’s protests prove conclusively what we already know to be true – namely, that where there is repression there is resistance.

SYMBOL OF IMPERIALISM

Pentridge was born out of the domination of Australia by British imperialism in the 19th Century. Today it serves as a monument to the fascist bestiality of the U.S., British and Japanese imperialists and the local quislings who dominate Australia economically, politically, and culturally. This statement may seem rhetorical and emotional but the situation in Pentridge, with its emphasis on psychological as well as physical punishment, is similar to a concentration camp. It is an institution of fascism in the sense that it is an institution based on overt reactionary violence. Its existence and present function and nature proves that the state is a machine for the oppression of one class by another, and, that under capitalism this means the oppression of the working class by the capitalist class.

Let me elaborate by relating my own personal experiences and some of the experiences of other prisoners, in the form of a brief description of the divisions which constitute Pentridge.

‘A’ DIVISION

We are currently located in ‘A’ Division. Relatively speaking, ‘A’ is the ‘best’ Division in Pentridge. The prisoners throughout Pentridge have waged heroic struggles which have improved conditions in ‘A’ Division and led to a reduction in the use of violence against the prisoners by the screws. Applying the old colonial principle of ‘divide and rule’, one very small section of ‘A’ Division is reserved for the elite of prisoners; the ‘aristocracy of prisoners’ if you like. This section (consisting of about ten out of 160 cells) is used as a public relations centre. Any visiting magistrates of government inquiry teams are promptly directed to this section. The prisoners there are the ‘good boys’ who earn $2.50 a week in positions as head librarian and the like. The real ‘A’ Division is the ‘A’ in which the vast majority of prisoners exist. No T.V. sets, record players or heaters for these prisoners on $1.30 a week – just mental and psychological anguish, pre-planned long term physical destruction, and cruel, sadistic humiliation. This is the real ‘A’ Division, the ‘A’ Division in which the vast majority exist.

‘B’ DIVISION

‘B’ Division lacks the relative freedom of life in ‘A’. Conditions are far worse and the intensity of manual labour and degradation by the authorities are far more extreme. ‘B’ is organised on the basis of strict regimented discipline. One prisoner who spent some years in ‘B’ has informed me that the discipline in ‘B’ reminded him of the discipline enforced upon him in ‘H’ Division. Unlike in ‘A’ where you are permitted to occasionally forget to address the screws as ‘sir’ in ‘B’ any such omission is sometimes met with physical assault, but more typically, verbal abuse. A report received from another prisoner who had just ‘graduated’ from ‘B’ to ‘A’ claims that ‘the tense atmosphere in ‘B’ can be sliced with a knife’. Again, I could not help but recall those words of Chairman Mao’s ‘Where there is repression there is resistance’.

‘C’ DIVISION

‘C’ Division looks like a scene from a ghost town in one of those old cowboy movies. The cells are literally iron bolted stables. Even the government declared ‘C’ Division a ‘condemned’ division some years ago but still nothing has been done about it. ‘C’ is renowned throughout Pentridge for its rat problem. Huge gaps exist in the cell doors which allow the rats to enter each cell. Naturally, there is a much higher rate of disease in ‘C’ than in ‘A’. ‘C’ remains unsewered. Prisoners must contend with only a small night pan. One old prisoner who spent several years in ‘C’, explained to me that during summer he used to sleep on the floor of his cell with his face near the gap below the door because the general stench of ‘C’ and the specific smell of his cell used to become unbearable.

‘D’ DIVISION

‘D’ Division or ‘Remand’ is second only to ‘H’ Division. I spent some time in remand. The cells in ‘D’ are basically toilets equipped with a bed. The entire cell smells of semi-sewered toilet. Even by the lowly standards of bourgeois morality the conditions are appalling. The ‘D’ prisoners spend all day long pacing up and down the remand yard. This yard consists of a small triangular concrete yard surrounded by three huge blue-stone walls which block out any sunlight. One shower, one open toilet, and one clothes hoist allegedly make the yard suitable for fifty men. One prisoner I met had spent 12 months in remand awaiting trial. In this sense, remand is a sort of ‘limbo’. It represents an in-between world between the courts and prison.

‘E’ DIVISION

Any prisoner may see the prison doctor at ‘E’ Division and receive medical or dental attention. ‘E’ is basically a dormitory for sick prisoners. It is apparently based on very strict discipline and I have been told some prisoners are sent to ‘E’ as a form of punishment. There is only one doctor to cater for Pentridge’s 1,200 prisoners.

‘F’ DIVISION

‘F’ is simply a dormitory for about 30 prisoners from the remand yard. The rest of the remand prisoners retire in ‘D’ Division cells which I have already described.

‘G’ DIVISION

‘G’ is the Prison Psychiatric Centre. Not all prisoners who need psychiatric care get it though. In ‘A’ at the moment, for one example, is a prisoner who just sits in the sun trembling all day. He studies his hands as though inspecting each intricate part of the mechanics of a clock, for hours on end. He showers each day but can never remember where the shower room is located. He clearly requires urgent psychiatric attention.

‘J’ DIVISION

Before describing the notorious ‘H’ Division, let me say something about ‘J’ Division. Presumably ‘J’ stands for ‘Junior’ as the prisoners here are aged between 18 and 21. Some of these lads are beaten and humiliated by the senior authorities and their lackeys, the screws. All sorts of sexually perverted acts are launched against some of these basically decent young Australians. Looking down into the ‘J’ Division Labour Yard and seeing these tired, ragged, illiterate, scruffy uniformed young prisoners, I could not help but recollect some of the apt descriptions of the Pentridges of yesteryear as reported by Charles Dickens in ‘Little Dorrit’.

‘THE SLOT’, ‘H’ DIVISION

The maximum security Division is ‘H’ Division or, to use the prison slang, the ‘Slot’. The ‘H’ stands for ‘Hell’. I have interviewed ex-’H’ prisoners who have informed me of the heinous sadistic crimes launched against them by the screws in ‘H’. I entered ‘H’ two days ago to collect some laundry. It would not be an exaggeration if I were to describe the effect ‘H’ had on me as ‘spine chilling’. The ‘Slot’ is a small building guarded at the front entrance by two huge brutal looking screws. The first thing I noticed on entering the front doors with my laundry trolley was a large mirror (used to observe anyone approaching) with a long horizontal crack in it. I later discovered that a prisoner had been thrown onto the mirror. The whole situation struck me as nightmare like and unreal. It was very macabre, like something out of Luna Park’s Chamber of Horrors, only extremely serious. The two screws reminded me of ‘heavies’ from a Boris Karloff movie. They abused me and attempted to humiliate me. Why? Simply because I dared enter the ‘Slot’ and leave with my trolley full of laundry. ‘H’ prisoners are put to work in the ‘Labour Yard’ where they spend hours each day breaking up rocks. They are marched around the yard with military discipline. Most of these men have been sent to ‘H’ for breaches of internal discipline. Many of those who have visited ‘H’ still have the signs to prove it: scars, broken noses, etc. Conditions are so bad that two ‘H’ prisoners have hung themselves during the past few years. Others cut their wrists or throat in order to be removed from ‘H’ and sent to hospital. One ‘H’ prisoner swallowed a 12 inch long metal towel rack. He was sent to hospital and the rack was removed by surgical operation. He was then returned to ‘H’ and promptly swallowed the metal towel rack once more.

‘H’ from what I can fathom, rightly deserves the title: ‘Hell’. You have probably heard about the infamous ‘Bash’, or at least seen the slogans painted on factory walls around North Melbourne, ‘Ban the Bash’. The ‘Bash’ has recently been abolished as a result of the prisoner’s rebellion and the government’s inquiry. I met one 26 year-old prisoner who had just been released from ‘H’ after 3 and a half years! Snowy white hair, badly injured eyes, and sickly yellow skin, this once dark haired, normal, healthy young Australian has been subjected to one of capitalism’s ‘rehabilitation’ programmes. He related to me his experiences in ‘H’ when the ‘Bash’ was a formal daily occurrence. The screws would order individual ‘H’ prisoners to jump into the air. When the prisoner landed after having jumped into the air, he would be told: ‘You were ordered to jump into the air, you were not told to land’ and promptly given a bashing. On other occasions prisoners in ‘H’ would be directed to march into cell walls and keep marching until badly bruised and bleeding. Others would be humiliated and forced to imitate animals.

All this in the name of ‘rehabilitation’!!

A few days ago a riot broke out in ‘H’. I saw the smoke, heard the screams, and saw the screws frantically running hither and thither. Again I recalled those wise and correct words, ‘Where there is repression there is resistance’.

THE PRISONERS AND THE SCREWS

Now I would like to give you my general impressions of my fellow prisoners and the screws.

My fellow prisoners are, generally speaking, courageous and kind-hearted men. Most have an instinctive hatred of the capitalist class. They are all political prisoners in the sense that their alleged crimes are socially induced. No murderer is born a murderer, no rapist born a rapist. The various types of social pressures exerted on decent working people by the corrupt and exploitative capitalist class force some people to resort to crime. But what do we mean by ‘crime’? Is the man who steals food (or money to buy food) for his family really a criminal? And what of the unemployed or unemployable, the so called ‘vagrant’? Ah, but, you will ask, what of the man who murdered and raped his sister? Surely, I reply, he needs help and pity, not sadist-based punishment. He should be, to coin the popular stereotyped expression, ‘rehabilitated’. But the notion of ‘rehabilitation’ is by no means a neutral concept. The fundamental question remains ‘rehabilitated’ to what sort of social system and to what sort of value system? The capitalist class can be so hypocritical! They maintain and profit from the social system based on exploitation in the form of private appropriation and the value system based on selfishness and yet they seek to ‘rehabilitate’ the convicted criminal to re-accept those very same social conditions and values which engender crime in the first place!!

This is the same capitalist class which gives out-and-out ‘Sanctity of Law’ to mass destruction of property and people in Indo-China and to the foreign plunder of Australia, yet send basically decent working people to the Pentridge concentration camp for alleged ‘crimes against private property’. Of course there are criminals and there are criminals. But getting to the root cause of the problem, the real criminals are the very same hypocrites who uphold the present penal system. I refer of course to the criminal capitalist class which, like a lowly parasitic thief, thrives off the labour of others.

‘PRISON POLICE’

Now let me comment on the screws, the prison police. Just as it is often claimed that there are ‘good’ as well as ‘bad’ police, so it is said there are the ‘good’ screws and the ‘bad’ screws. The role of the screws is really indefensible. They maintain ‘law-n-order’ within the concentration camp. Some do it with a smile, others don’t give a damn, others take great pride in their work. This latter type is the most prominent, active, and vocal within Pentridge. All the screws are armed with either batons, guns, or .303 rifles. The latter type of screw is sadistic and gains pleasure from humiliating the prisoners. They abuse and try to humiliate us. In ‘H’ Division for example, prisoners are forced to lie on their stomachs naked on their beds and hold the cheeks of their back-sides wide apart for the screws to examine. In ‘A’ Division, one cold frosty morning I was ordered by a clenched fisted screw to ‘Get you f…… hands out of your f…… pockets’. (They are very foul-mouthed creatures.) However, in trying so desperately to humiliate others, they really only humiliate themselves.

The screws and prison authorities fear the prisoners’ rebellion. Like all reactionaries they are superficially strong but essentially weak. Like the vast majority of prisoners I hate the screws and prison authorities with an intense class hatred.

The day is not far off when justice will be dealt to the screws, the prison authorities, and the entire ruling class!

Barry, Brian and Fergus outside Pentridge in 2012

Pentridge Prison’s history of horror

THE crumbling prison walls of Pentridge will soon take on a new role and it couldn’t be further from it’s bloody past.

CRIMINALS could probably hear the faint torturous screams of their inmates echoing through cold, crumbling prison walls as they were hung among the cells.

Pentridge Prison, which closed in 1997, housed some of Victoria’s most notorious criminals, including Melbourne underworld figure Carl Williams and members of the Kelly Gang.

But now the prison’s D Division, the execution wing and the place many sadistic criminals took their last breaths, will be turned into a new dining hotspot.

The dining precinct is part of developer, Future Estate’s $1 billion ‘Coburg Quarter’ project and some of the site’s key heritage features such as laundry machinery and solitary confinement cells will be restored and showcased as a feature within the venue.

The restaurant, bar, brewery and laneway precinct should be complete in October and will have an ambience that couldn’t be further from chained prisoners and bloody brutality.

Graeme Alford, a former Pentridge inmate, told the Herald Sun it wasn’t an area for the faint-hearted.

“The first couple of weeks I was in Pentridge were really unnerving,” he said.

“D Division wasn’t a great place because people were on remand, so they hadn’t been sentenced, and you had a lot of people who couldn’t handle it.”

“At night you would often hear guys yelling and screaming, maybe withdrawing from drugs or whatever,” the former embezzler and armed robber said.

When parts of Pentridge were turned into luxury apartments just over a decade ago, it was feared the history would be demolished along with some of the bluestone walls.

The D Division, in the heritage-listed jail, was a place where Ronald Ryan and Mark ‘Chopper’ Read served parts of their sentences.

Ryan was found guilty of murdering prison guard George Hodson and was the last person to be legally executed in Australia in 1967.

He became a notorious criminal after he planned a great escape from the prison when he discovered his wife was seeking a divorce.

In December 1965, Ryan and a fellow prisoner, Peter Walker, scaled a 5m wall with help from two wooden benches, a blanket and a hook.

They were then caught by prison warder Helmut Lange but the pair overpowered him, stuck a rifle into his back and demanded he open the prison gate.

While on the run the prisoners robbed a bank in Ormond.

They were recaptured 19 days after escaping, when police received a tip-off about their whereabouts.

In the hours before Ryan was executed, he scribed a noted on some toilet roll, one to authorities protesting his innocence and one to his daughter saying his conscience was clear.

Pentridge Prison walls also smothered Gregory John “Bluey” Brazel, described as one of the prison’s most vicious and manipulative inmates.

He is serving three life sentences for murdering prostitutes Sharon Taylor and Roslyn Hayward 26 years ago and gift store owner Mildred Hanmer in 1982.

He will be eligible for parole in just four years time.

The cruel crim also conned an old lady into depositing $30,000 into a TAB telephone betting account, stabbed three prisoners and assaulted police and prison officers.

Prisoners were kept in their cells 23 hours a day and the Herald Sun reported the shocking tales of former chaplain Peter Norden.

“One of the first experiences I had when I visited in 1976 was meeting a 17-year-old who had been raped the night before in one of the dormitories. Now that was a very significant experience, a shocking experience, for me,” he said.

“In many ways the chaplain was the only person in the place that could be trusted because the prisoners did not trust one another, they didn’t trust staff and they didn’t trust those employed by the prison service because everything would be used against them.”

Pentridge Prison is one of the most haunted in Australia, with the “ghost” of Chopper Read said to be lurking in the prison shadows.

During a 2014 ghost tour, a group of Pentridge Prison visitors claimed they heard the voice of Mark ‘Chopper’ Read tormenting them.

Read was depraved, beyond robbing drug dealers and tormenting underworld figures, he also convinced a fellow inmate to cut off both his ears to help Read escape the H Division, which protected high security prisoners and disciplined them.

It is also believed the brutal crim used bolt cutters and blowtorches to amputate the toes of his victims.

He died from liver cancer in a Melbourne hospital just three years ago.

Jeremy Kewley, who has led ghost tours throughout the prison, told the Today showthere was a loud bellow coming from Read’s cell in the D Division.

“We had a group of lawyers on the tour and suddenly from the dark end of the cell we heard an incredibly loud and aggressive voice yell ‘get out’,” Mr Kewley said.

“It echoed through the entire building and we just sort of froze, it was just such a shock to me.”

Some of the lawyers on the tour smirked and Mr Kewley had to assure them it had never happened before and they weren’t being conned.

They even called police and security to search the D Division, where 11 prisoners were hanged.

“It’s a sad and scary place,” he said.

Pentridge: Infamous prison’s ‘extreme’ transformation into luxury village

Its towering bluestone walls have housed some of Australia’s most notorious criminals, but now the infamous Pentridge Prison is shedding its image of convicts and cutthroats in favour of cafes and cinemas.

After being decommissioned in 1997, and trading hands between private developers for more than a decade, the sprawling grounds, guard towers and cell blocks of Pentridge Prison are now being turned into a luxury development.

The site will include apartments, boutique shops, cafes and a 15-screen cinema in what developers say will be a “well-designed urban village that invigorates an important historical asset.”

So is this a necessary modernisation, or papering over our history in search of a dollar?

‘Where the bad people go’

Author and photographer Rupert Mann has spent years documenting the site and interviewing former prisoners and staff who called the prison home.

Mann has compiled his findings in a new book, Pentridge: Voices From The Other Side, and said like many Australians, his fascination with the place began at an early age.

“I remember Pentridge when I was much younger, maybe six years old, going past the walls with my father and asking him ‘What’s that place?’,” he told News Breakfast.

“He told me, ‘That’s where the bad people go.’ I kind of had this fascination from then with Pentridge.”

The name alone is part of Australia’s folklore and the infamy is well deserved.

Between 1850 and 1997 it bore witness to scenes of great violence and depravity, including the last legal execution in Australia, held in 1967. And it housed the likes of Ned Kelly and Chopper Read.

As Mann notes in his book, there were 75 deaths at the prison between 1973 and 1997 — of which only 13 were by natural causes.

And when the Jesuit social services opened it up for public tours only a few months after the last prisoners departed, they had to invest $100,000 to bring it in line with basic health and safety standards.

Back in 1978 former governor Bob Gill made headlines when he remarked to a journalist that the facilities were so bad “if I put my dogs in conditions like this, I’m sure I’d be reported to the RSPCA.”

Mr Gill is one of 15 people to offer their account of Pentridge in Mann’s book, saying some “bloody crazy crap” went on there.

“Morale in that bloody place was at rock bottom. It had an effect on the staff, working in there,” he said.

Indigenous actor Jack Charles also offers his story, detailing how he spent time in and out of jail in his younger days, including arriving at Pentridge about the age of 18

“I saw really nasty things. Pentridge was a violent place,” he said.

“I remember thinking sometimes that the screws (guards) could come in to your cell at any time and kill you … It was a young man’s paranoia, I suppose.”

‘Don’t sweep history under the carpet’

Mann doesn’t romanticise the stories of Pentridge Prison, but he does seek to preserve them.

He worries the redevelopment will disconnect Australians from the past and the lessons it can teach us.

“By physically demolishing the more recent layers of the prison, a chasm is placed between us and the events that happened there,” Mann wrote.

He hopes his book can bridge that chasm.

The Shayher Group bought the land in 2013 and is in the process of developing it.

Public events are already held at the site — both cultural and historical — and this week a guest criminologist will give a talk on the way crime has changed over the years.

Mann said more than half of the former prison inmates and staff he approached didn’t feel comfortable talking or revisiting the site, and many had mixed feelings about the development.

History of Pentridge Prison

- Pentridge was built in 1850 in Coburg in Melbourne’s north

- H-Division was for high security, discipline and protection of prisoners

- Jika Jika or K-Division housed the maximum-security-risk inmates

- Ned Kelly, Julian Knight, Chopper Read and Squizzy Taylor all served time there

- Ronald Ryan, the last man executed in Australia, was hanged at Pentridge

- It closed in 1997

“Many people said raze the place, demolish it, make it into a park, and forget it,” he said.

“But many people do feel that the development is too extreme and too much has been lost at Pentridge and it really can’t tell its story any more, not in the way it could when I did the book.

“I think that’s why a lot of people, a lot of these guys got into the book because they could see that their personal history, their personal story that they lived was being swept under the carpet in order to make the place palatable and sellable.”

Blending the old with the new

“What we’ve realised over the years is that this site needs to be activated in terms of the public,” spokesman Anthony Goh said.

“We’re really trying to create an open space where you can come have lunch, dinner, breakfast as well.

“It’s a place where you come and meet people [and] go to the fancy Palace Cinemas.

“The majority is supporting us and unfortunately the majority, when they support something, don’t say that much.”

It’s estimated the redevelopment will cost about $1 billion and take up to 10 years to complete.

Heritage Victoria guidelines mean Shayher Group must preserve the exterior of certain buildings of significance, but the developers have plans to repurpose the insides.

This could mean turning cell blocks into an art gallery, or turning four small cells into one large hotel room.

“There’s a line of thought which says that in preserving heritage, ok preserve what is old, but then we need to offset it with the new,” Mr Goh said.

“We’re trying to get the message across that we’re not destroying heritage here. Everything has gone through Heritage Victoria.

“And secondly, there is some balance here in making the site economic in order for it to go forward by itself in the future.”

Reference

- Hell Division: Pentridge Prison’s section for the baddest and maddest, The Age, 1 April 2015, by John Silvester https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/hell-division-pentridge-prisons-section-for-the-baddest-and-maddest-20150401-1mcgg4.html

- ‘Nightmare like and unreal’: the letter from Pentridge, Overland, 25 January 2018, by Barry York https://overland.org.au/2018/01/nightmare-like-and-unreal-the-letter-from-pentridge/

- Pentridge Prison’s history of horror, News. Com, by Olive Lambert https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/real-life/true-stories/pentridge-prisons-history-of-horror/news-story/a041aecccc4e5c1761235dc75818fecd

- Pentridge: Infamous prison’s ‘extreme’ transformation into luxury village, ABC News, 30 November 2017, by Patrick Wood https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-30/pentridge-from-infamous-prison-to-luxury-penthouses/9200756