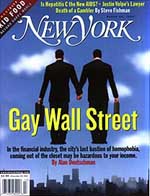

Joe Daniel’s salary had broken the six-figure mark, and he had just received a promotion to vice-president. But something was about to sink his career on Wall Street: He couldn’t bring himself to lie.

It was a Monday in late June, and Daniel had reported for work at the securities division of Dresdner Bank, Germany’s second-largest. When a colleague remarked on his suntan, Daniel explained that he had spent the weekend at his beach house. Where’s your rental? asked his co-worker.

For most of his colleagues, the question would have been an innocuous one. For Daniel, it posed a dangerous dilemma.

A quiet, button-down executive with master’s degrees from both Harvard and Yale, Daniel was hardly an activist.

Like most other gays on Wall Street, he had lived a strictly closeted existence at work. In the past, he would have constructed a plausible cover: a particular Hampton that he could bluff some knowledge about, the name of a fashionable restaurant or two. But after four years at the firm, he was tiring of the charade.

His beach house was on Fire Island, he replied. At the Pines. His colleague looked stunned. Daniel had just outed himself.

Until then, Daniel’s career had been proceeding according to plan. His boss complimented him regularly on his work and, Daniel says, rewarded him with a big promotion a few days earlier. The firm had printed new business cards and stationery and even fabricated a new signboard for the door of his office. A memo announcing his new position was distributed to all departments.

But according to Daniel, gossip about the Fire Island remark quickly reverberated through the office and soon reached his boss, George Fugelsang. In the past, says Daniel, Fugelsang, a gruff, fiftyish executive who heads Dresdner’s North American division, had made crude anti-gay jokes. Suddenly he seemed more careful about his language. But beyond the superficial correctness, something was very wrong. Though Daniel had assumed the duties of a vice-president, Fugelsang never got around to signing the papers that would make the promotion official. Instead, Daniel says, he was relegated to a kind of purgatory, shunned by his boss and many of his colleagues.

The situation festered for nearly a year, until the following April, when Daniel, emboldened, decided to force the issue. He approached Dresdner’s personnel department, asking whether the firm could extend the same health benefits to the domestic partners of gay employees that it provided to the spouses of straight ones. A few days later, he was laid off in an abrupt “downsizing” of his department. Daniel was the only person fired.

Unemployed for nearly a year, Daniel is now suing Dresdner Bank for $75 million under a New York City statute that outlaws bias based on sexual orientation. It is a landmark case, Wall Street’s first gay-discrimination lawsuit ever, although other clashes have been secretly settled in arbitration. In order to avoid unwanted publicity, brokerage firms require new hires to sign an agreement stipulating that employment disputes will be resolved by a Wall Street arbitration panel rather than by the courts. Intent on proving a point, Daniel’s lawyer, Madeline Lee Bryer, circumvented this agreement by suing the foreign bank that owned his firm, not the New York securities outfit he worked for.

Attorneys for Dresdner insist that Daniel’s promotion was not official and that sexual orientation played no role in his “restructuring.” The case is currently in pretrial discovery, and after a flurry of publicity, the presiding judge issued a gag order on both litigants. Nonetheless, it has drawn serious attention to a rarely discussed issue, spurring anxiety not only among Wall Street firms suddenly worried about lawsuits but also among their largely closeted gay and lesbian employees.

How many gays and lesbians are there on Wall Street? James J. Cramer, the seemingly omnipresent and omniscient hedge-fund manager, can’t name any. Jessica Reif Cohen, the top-ranked analyst of entertainment and media stocks, doesn’t know any gays at her firm, Merrill Lynch, which has nearly 10,000 employees in New York City alone. Within the broader community of research analysts, “there’s only one person I even think is gay,” she adds: a middle-aged guy who supposedly lives with his mother, a fact that has provoked gossip at his firm because “almost everyone else is married with children.” Elizabeth Goldstein, who recently left Bankers Trust after six years as a star on the trading desk, says, “I can’t think of anyone. I’m sure they exist, but it’s very, very, very, very quiet.” When a trader talked about attending a lesbian wedding, she recalls, “People’s mouths were wide open. It was totally foreign to their experience.”

Welcome to turn-of-the-century Wall Street. In a city where openly gay professionals are commonplace in such industries as media, advertising, and law, Wall Street remains a notable exception – one where the prevailing mind-set seems more characteristic of 1959 than of 1999. Like the military, the financial world promulgates an unwritten policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” which affords gays and lesbians a chance to prosper, and even rise to prominence, but only if they deliberately obscure their personal lives.

“Living in a liberal, diverse environment like Manhattan, you realize that banking isn’t really part of that,” says one closeted banker. “It’s a different world. My boss and my boss’s bosses live in very sheltered communities in Westchester and Connecticut. They don’t live in the Village or the Upper West Side. They find it very difficult to manage sexual diversity.”

For young gay Wall Streeters, he says, “it’s very common to have gay friends, party on the weekend, live in Chelsea, then put on a suit and take the subway to work on Monday. No one needs to know you spent Saturday night at the Roxy.”

This enforced invisibility is all the more remarkable given the fact that gays are actually all over the Street, working as traders, brokers, securities analysts, money managers, and investment bankers at such major houses as Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, CS First Boston, and Salomon Smith Barney as well as at a slew of smaller private-investment firms. Many hold positions of considerable stature. Two of the street’s best-known firms, Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette and Drexel, Burnham Lambert, were founded in part by gay men; three others include gays at their very top levels.

Walter Schubert, the founder of the Gay Financial Network (gfn.com) and the only openly gay member of the 1,365-member New York Stock Exchange, estimates that there are thousands of gay financial professionals in New York and perhaps tens of thousands nationwide. A gay Wall Street organization called New York Bankers’ Group boasts 300 members; more than 100 were on hand for a Christmas party last December. Still, the membership list is kept strictly secret, and six of the group’s eight board members are not out at work.

For many gays and lesbians, Wall Street is a not-so-quaint throwback – a testosterone-drenched frat house complete with ritual hazing. One man came to work to discover the word faggot Magic Markered on his office wall; another found nude pictures from a gay magazine glued to his computer. For most, however, the pressure is more subtle. “It’s like high school all over again,” says one mid-level trader. “You hear people talking and joking and whispering, and you’re sure it must be about you.”

One gay banker recalls a group meeting with his boss (who was a managing director) and another vice-president to discuss a prospective client. Paging through the company’s annual report, his boss opened it to the photo of the company’s president. “God, this guy looks like such a faggot!” he exclaimed in disgust, looking directly at the employee, who wasn’t out at work. “No offense,” he added sarcastically. An investment banker says she was told she was being passed over for a promotion because “the firm wanted to uphold a family-values image.”

Not surprisingly, fear and paranoia persuade all but the boldest gays and lesbians to conceal their private lives. Some count on a stable of attractive “girlfriends” and “boyfriends” to escort them to business dinners and company functions. One investment banker asked a woman friend to leave a breathless outgoing message on the answering machine he shared with his male lover. Another decorates his desk with portraits of friends’ children that he passes off as his own.

In some ways, gay white males on the Street have enjoyed an advantage over other minorities – blacks and women – because they can pass as straight white males. In the fifties and early sixties, when Wall Street was a less macho place, gay men in particular found it easy to hide in open sight. These men were perceived by their clients – conservative, midwestern CEOs – not as New York queers but as cultured, urbane gentlemen.

The code of silence was so strict that in 1983, an executive named Robert Hudson co-owned a brokerage firm with a gay partner, and neither realized that the other was also gay. But as the culture of Wall Street turned increasingly rabid during the late eighties, the Gentleman Bankers of an earlier generation were shoved aside by Swinging Dicks so big they made even Tom of Finland’s look modest.

AIDS further changed the equation. Like every other industry in the city, Wall Street suffered a number of aids deaths, the majority of which were disguised as pneumonia or cancer in death notices. Among the epidemic’s earliest casualties was Leon Lambert, a name partner at then-mighty Drexel Burnham Lambert and a familiar figure on the city’s gay circuit. Activist Larry Kramer, who was invited to attend Lambert’s funeral, remembers that Henry Kissinger and David Rockefeller delivered eloquent eulogies – but neither mentioned that the financier was a closeted homosexual or that the real cause of his death, according to Kramer and others, was aids.

The epidemic also pitted gay activists against their more conservative Wall Street counterparts. Up until the eighties, most activists were willing to grant closeted tycoons their privacy, but as the gay movement took a radical turn, Kramer and his cohorts dispensed with the rules. Magazines like Outweek began outing closeted titans like David Geffen and Malcolm Forbes. In a much-talked-about speech in 1982, later published in his book Report From the Holocaust, Kramer took aim at one of the Street’s most celebrated figures, Richard Jenrette, for not taking a more public stance during the epidemic.

At the age of 30, Jenrette co-founded, with two of his Harvard Business School classmates, the investment-banking firm Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, which now grosses more than $5.4 billion a year. In the late sixties, Jenrette launched Alliance Capital, which became one of the world’s largest money-management firms, and he went on to head the Equitable, leading a stunning turnaround at the struggling insurance giant. Now retired at 69, he remains the courtly southern gentleman, favoring conservative Brooks Brothers suits. An avid art collector and an antiques buff, he spends most of his time restoring old mansions. He currently owns six, including an 1840 plantation in South Carolina, an 1838 house in Charleston, and a spectacular 1820 house on the Hudson River.

Though scrupulously low-key about his sexuality, he has lived with the same partner for nearly two decades and occupies a position on the periphery of the Gay Establishment. Kramer says that when Gay Men’s Health Crisis was founded in the early eighties, Jenrette was among the first to write a check, but the financier spurned subsequent requests to donate more or to serve on the GMHC board.

“The fact is, Jenrette has benefited a lot from the strides of the gay movement,” argues Kramer. “We, in turn, need visible people like him to self-identify. Why are gays on Wall Street living by the fears of a previous generation?

“If Dick Jenrette had been a real hero and honest about his sexuality, maybe the current generation would be bolder,” Kramer adds. “At this point, he has absolutely nothing to lose.”

Jenrette is just as vehement in response. “I’ve always thought a person’s sex life is their own business,” he bristles when asked about criticisms such as Kramer’s. “I don’t see why I have to declare my sexuality. I don’t need to have a confessional. I think it’s terrible: Are you gay or straight? People are everything. I think it sets a worse example if everyone declares how they do it. Orally, anally, with the family dog? One’s personal life is a very private thing. I think my personal life is my own.”

While many younger Wall Street gays cite Jenrette’s unwillingness to take the lead as a disappointment, Andrew Tobias, the best-selling financial writer and gay memoirist, believes the reticence of people in Jenrette’s generation is understandable. “They came of age at a time when to be gay was an abomination, like cheating on your wife,” he says. “The younger, more junior gay people on Wall Street are proud, but they say, Why jeopardize the chance of making big money?”

In fact, for younger gays, many of whom came out in the liberal atmosphere of college only to find themselves pushed back into the closet at work, the transition can be especially difficult. “The anti-gay jokes are common, accepted, and almost encouraged,” says Robert Fenyk, a young Merrill Lynch broker who left the firm in disgust in 1994. “When traders make anti-gay jokes, they really do it because they are anti-gay, versus just ‘busting’ on a Brooklyn guy because he has an Italian accent. I don’t think the straight community on Wall Street wants to know you’re gay. They don’t want to learn how to deal with gay men. I don’t see full acceptance in my lifetime, and I’m 31.”

While there are no particular fiefdoms at the big financial firms that are uncommonly tolerant of homosexuality, some institutions and divisions are reportedly more tolerant than others. Most gays and lesbians take pains to avoid the trading floors – raucous boys’ clubs that one gay trader compares to “a holding pen at Rikers – but less refined.”

Nevertheless, there are exceptions. One trader began his career in mergers and acquisitions but transferred after just two years, partly because he figured that the trading floor would be easier to take than the suburban-country-club socializing expected of investment bankers: “Sure, there’s an awful lot of machismo on the trading floor. There are guys who smash phones. There’s a lot of shouting, talking about football, going out for beers after work. But I don’t find that particularly problematic. I always thought that M&A was a more difficult environment to be out in, especially at a senior level, when you’re forced to take clients and their wives to golf events.”

While Wall Street may talk up the meritocratic ideal, its entrenched culture is still socially conservative. Wall Street firms do keep very close tabs on who produces what profits, but they don’t always pay the individuals in direct proportion to their performance.

This discrepancy is particularly pronounced when it comes to bonuses, which often constitute the biggest part of a professional’s pay. Elizabeth Goldstein, the former Bankers Trust trader, says that married guys with children are usually able to plead rather effectively for the largest bonuses, claiming they need the money for things like private-school tuition.

Their supervisors – often family men with financial burdens – empathize with them and pay up. Single women and gay men tend to be shortchanged at bonus time, because they can’t make as effective a case for higher compensation. Since the system rewards married providers with children, it’s not surprising that many Wall Streeters seem to have unusually large families and traditional, stay-at-home wives. In this environment, a single gay man with no children – and a partner whose existence he doesn’t dare discuss – seems conspicuously out of place.

In fact, some find it especially hard to maintain relationships in the atmosphere of Wall Street. “Every time I’d find a relationship, my company would move me to another continent,” sighs one trader. “If you’re straight, the firm will make provisions to move your wife or girlfriend along. Because you can’t be open, they move you around at will.”

James Pepper, an openly gay managing director at Brundage, Story and Rose, a money-management firm, describes the dilemma of a closeted investment banker currently under consideration for a lucrative partnership at one of the Street’s most prestigious houses. “If he were out, they might not feel comfortable having him as a partner. Yes, they will shut their eyes if he makes a strong economic contribution. But if there are five partnerships available and six people who make equal money, then they won’t choose him.”

There are exceptions, of course. When Joe Cherner was trading 30-year Treasury bonds at Kidder, Peabody in the eighties, his lover accompanied him to Christmas parties and social events. “My sexuality had very little to do with my job,” says Cherner, who was president of his class at Columbia Business School. “I don’t see where sexuality is or should be an issue. In my specific instance, I didn’t have a problem being accepted.” But Cherner left Wall Street after seven years.

Though gay bankers and traders may know one another by reputation, they by and large take pains to avoid one another at work. A loose social network of gay financial types sometimes hooks up at private homes and parties, but “when you run into someone that’s gay during the day, you’re not gonna ask them how their boyfriend is or anything,” says one banker. It’s not something you want to bring up.” At Goldman Sachs, two partners in a long-term relationship were so worried that their secret would be exposed that they didn’t speak to each other at Goldman’s offices.

In 1983, a group of gay financiers at J.P. Morgan and Bankers Trust founded a professional association they called the New York Bankers’ Group, with the idea that it would allow them to share experiences and contacts. In the group’s early days, meetings were held at private homes, and many of the addresses on their mailing list read “Mr. and Mrs.” because members were pretending to be married.

Today, NYBG has more than 300 members, 70 percent of them male, ranging from traders in their mid-twenties to retirees, who meet monthly at various Manhattan locales. The majority are in commercial banking, but there is a large investment-banking contingent as well. Ironically, even the president of the organization, a 27-year-old working for a foreign bank, declines to be identified.

“We provide a way to network with other people in your institution,” he says. “Many people meet their boss’s boss or a close co-worker who they didn’t know was gay.”

Though the group’s president says NYBG members include senior executives at J.P. Morgan, Standard & Poor’s, Bank of America, Bear Stearns, and Bankers Trust, the group’s membership list is kept strictly confidential: NYBG internally publishes a networking directory that’s available only to members.

Last December, 106 members attended the group’s Christmas party at Flute, a swank champagne bar in an old speakeasy. NYBG events like this are “not cruisey,” says one NYBG member who met his first boyfriend through the group, “but a lot of business cards are exchanged. There are a lot of good-looking guys, professional and well-off – very high dating-and-relationship potential.”

More important, he says, he has found the Bankers’ Group to be a great way to find mentors – though for the most part, their experience has convinced him that it wouldn’t be advisable to be out at work.

Judging from their representation in groups like NYBG, Wall Street’s lesbians are even less visible and organized than their gay male counterparts. “There so much competition that most of us feel fortunate just to be here,” says “Gina,” who works in the securities operation of a major firm. “Plenty of people with strong credentials would like to sit in my chair right now.” A trader in her thirties, Gina is out to her family, friends, and neighbors but not to her co-workers, with the exception of her closest colleague, whom she told only after they worked together for years.

Personal lives are usually left alone, she says: “I wouldn’t lie ever, but nobody has ever asked me, Do you have a boyfriend? or Are you married?” But since the firm sent around an announcement saying that it was beginning to extend health benefits to domestic partners, Gina has pondered whether to participate: “I’m not worried about being fired, but I have no doubt that I’d be treated differently given the quite blatant, openly homophobic culture in sales and trading.

“When I’m on the desk, I hear not-nice things about people who are suspected of being gay: ‘Get me that faggot on the line.’… I’ve never heard any racial slurs on the trading desk, and though you hear things about women, they never say anything when I’m around. People have been trained to know better.

“There is progress,” she adds. “You don’t see strippers on the trading floor anymore as ‘birthday presents’ for traders, as there were in the early nineties. But the culture of the swashbuckling trader is definitely still there.”

Personally, she admits, she has little incentive to push for lasting change at the firm, since she isn’t committed to spending her entire career there, as most of her straight colleagues are.

“I don’t foresee a career on Wall Street,” she says. “I took the job to pay off my student loans. The money’s been great for a while, but it’s too oppressive an environment for me to stay here.” Instead, she hopes to start a second career, related to public service.

That’s not an uncommon ambition: In a field where it’s possible to earn enough in a few years to retire in your forties, Wall Street gays often pack up their windfalls and start new lives in philanthropic or political causes. aids organizations and gay-rights groups like the Washington-based Human Rights Campaign and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force are also supported by large pools of Wall Street money.

In recent years, in part because of the threat of lawsuits like Joe Daniel’s, dozens of firms have taken steps to officially ban discrimination against gays and lesbians. According to the Human Rights Campaign, New York-based firms that officially ban discrimination include the Equitable, Citigroup (which includes Travelers and Salomon Smith Barney), Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, and PaineWebber.

American Express, Bankers Trust, Chase Manhattan, J.P. Morgan, Merrill Lynch, and Scudder Kemper also offer domestic-partnership benefits for the partners of gay employees.

In 1998, a gay financial writer named Grant Lukenbill helped start a service called the Equality Project, which surveys financial firms and Fortune 500 companies on their workplace policies toward gay and lesbian employees. The group’s Website (www.equalityproject.org) lists companies that meet its seven requirements, which include diversity training as well as domestic-partner benefits and explicit anti-gay-discrimination policies.

Of the New York-based financial firms, only four make the list: American Express, J.P. Morgan, Merrill Lynch, and Bankers Trust. (Out-of-town firms on the list: BankAmerica in Charlotte, Charles Schwab in San Francisco, and BankBoston.) In any case, even Lukenbill admits that stated policies sometimes don’t make much of a difference. “Some of the companies with the best policies,” he says, “have people with the worst anecdotal examples to the contrary.”

While Bear Stearns does have an official anti-discrimination policy, its existence is news to chairman Alan “Ace” Greenberg. “I don’t think we need one,” he says. “I think it’s clear that we wouldn’t tolerate that kind of thing. All we look for is smart, hungry people who want to be rich. I don’t give a damn what they do at home. We don’t discriminate against anybody,” he jokes. “We even hire Jews!”

Despite official advances, most gay Wall Streeters feel it’s still too risky to venture out. “My manager doesn’t have a problem with gays, but what about my next manager?” asks an experienced broker at one of the biggest firms, who believes his bosses could fire him at will without worrying about discrimination charges. They could simply claim that he didn’t meet performance goals, since every year he’s required to agree to new accounts and greater assets – incredibly high targets that only a tiny percentage of brokers actually attain. “They’ve always got that over you,” he explains. “I’m constantly seeing people fired.”

Those who are openly gay outside work worry about colleagues’ finding out. One broker at a small, stuffy, conservative firm agreed to be filmed for a documentary about a gay march, but he was wary when the producers said they wanted to show the film in a city where he had clients. After much prodding, they agreed to run it only in regions where he had no clients, so the identification of his homosexuality wouldn’t hurt his business. “My clientele is 99 percent heterosexual,” he explains. “They’re high-net-worth individuals, very well-off, and a lot of them are conservative in their political views.”

Sometimes, even the most careful precautions misfire: In a scene out of a Paul Rudnick comedy, “Keith,” an executive at a major investment bank, agreed to an after-work date with his boyfriend at a bar near his office. The boyfriend suggested the location, which he thought was a “gay lounge.” It was, but just one night a week. That evening, it drew a mixed crowd.

When Keith arrived early for the rendezvous, the scene was set for a farce. He immediately ran into a straight associate who asked Keith to join him and a friend for a drink. As the trio talked, Keith noticed his boyfriend enter the bar and move quickly toward him.

Keith knew what would happen next. “It suddenly occurred to me that he was going to give me a kiss,” Keith recalls. “I wanted to put up my arms to block him. My reaction was horror, which is appalling.” Sure enough, the boyfriend kissed him on the lips. It was a chaste, closed-mouth “hello” kiss, but nonetheless, the straight financiers appeared shocked. On cue, they began talking about women, as if to prove their heterosexuality bona fides.

“It was a very awkward moment, and I was just happy to get out of there,” recalls Keith, who points out that he faced no repercussions. “The bottom line is, I don’t have a problem being myself. The danger in this business is being myself too loudly.”

For a long time, walter schubert felt the same way. Now 42, Schubert grew up in a conservative, Republican, Irish Catholic family in West Orange, New Jersey, where “it was just not okay to be gay,” he says. “I lived for many years with an inordinate amount of shame and guilt.” He hadn’t planned to follow his grandfather and father to the floor of the exchange. He really wanted to be a diplomat in the foreign service. But in 1977, when Schubert was a sophomore at Skidmore, his father was told by doctors that he had only six months to live. Walter, then 20 and the oldest of six children, quit school to learn the family business at the Big Board.

“My role was to be the provider for my mother, brother, and sisters,” he recalls. “I didn’t hesitate.” A year after his father’s death in 1979, Schubert became the youngest member of the New York Stock Exchange. He was 23.

“I knew from the start that I was going to have to face this, but I couldn’t construct a successful career being an openly gay man on the floor of the exchange. In 1980, it was a very conservative, conformist place that didn’t like anyone who was challenging to the status quo. To step out, to be even slightly different – people weren’t going to go for that.”

Trying to fit in, Schubert dated many women and was even engaged to be married – twice. But the pretense wore him down. “I was becoming unhappy, self-destructive. I started to sabotage my success. By the mid-nineties, after fifteen years of taking care of my family, I thought it was time to live my life.”

In 1993, he began coming out privately to friends and relatives, though he remained closeted at work. But by 1994, the rumors of his homosexuality were spreading wildly. “It was becoming an open secret on the trading floor. It was pretty uncomfortable,” he says. Finally, a colleague confronted Walter directly. “When I was asked on the floor, rather than being sheepish, I said yes. Twenty-four hours later, I was ‘the gay guy.’ Since then, I’ve been trying to get back my whole identity. It’s been a hard journey.”

When he came out, he held a meeting with his employees, many of whom feared that the firm would lose its customers. Schubert himself had the same fear. He told his people he’d understand if they wanted to leave. None did.

Others who have found mainstream firms too stifling have struck out on their own. In 1994, Robert Fenyk, who spent two unhappy years as a broker at Merrill Lynch, switched from Merrill to Christopher Street Financial, which promotes itself as the only gay-owned-and-operated brokerage and financial-advisory firm in the nation. At Christopher Street (actually located on Wall Street), clients and brokers can talk freely about financial-planning issues specific to homosexuals – tax laws, pension benefits, and how to pass estates on to partners. Founded in 1981, the company was recently taken over by a group of investors including Jennifer Hatch, a 38-year-old veteran of J.P. Morgan and Bear Stearns. It recently opened an office in Fire Island Pines and is planning other branches in Short Hills, New Jersey; Los Angeles; and four to six other cities in the next eighteen months.

Although Christopher Street had the gay market to itself for most of two decades, major firms such as Merrill Lynch and American Express Financial Advisors are also getting into the act. AmEx, in particular, has a reputation for fostering a socially active and politically vocal group of gay employees. Its efforts began five years ago, when an employee named James Law realized that he was the company’s only financial adviser in New York who was openly gay. Noting that the major firms had forfeited the lucrative gay market to boutique firms like Christopher Financial, he and a group of colleagues argued that AmEx should broaden its reach into the community.

The company responded by advertising in national gay magazines such as Out and pouring money into gay charities and organizations. “We’ve found that if we make a commitment to community relations, that’s how we get most of our clients,” Law says. Today, almost 300 of AmEx’s 10,000 financial advisers nationwide, including 30 in New York, are involved in its gay-and-lesbian network, although Law admits that a majority of these advisers are straight, not gay.

Dana Giacchetto, who runs the successful investment-advisory firm the Cassandra Group, says his company has also benefited by hiring openly gay employees and maintaining a welcoming attitude toward gay clients. “Because we focus on the entertainment business, we have a more open, creative client base,” he says. “We serve many, many gay people, and I think they find it easier to do business with us than with buttoned-up firms. For us, it’s not an issue at all.”

Ironically, even as their straight colleagues wake up to the potential of the gay market, many gay brokers remain ambivalent about marketing to other homosexuals. A salesman at a top New York brokerage watched quietly as a straight colleague asked for and received funding from the firm to run a promotional booth at a gay-and-lesbian convention. He realized that he wouldn’t be comfortable making the same request for fear of outing himself at the firm.

Why, in the end, if Wall Street is so inhospitable, do so many gays stay on? Perhaps because, like many of their straight counterparts, they accept that sacrifice is part of the bargain: Staying quiet, playing the game, ignoring the faggot jokes, getting a lap dance – this is the price they pay for a career that offers such lavish material rewards. “It’s a deal with the devil,” says one banker. “No one can say they didn’t know what they were getting into.”

One top gay bond trader relishes the conflict. “Lets face it,” he says, “there’s no place in the world you can make so much money so quickly. Wall Street is the ultimate boys’ club, and like all boys, they get off by pushing each other around and earn special points by bashing the fags. But it’s a culture that rewards performance and aggression. If you earn enough, and you’re mean enough, and you go with the flow, no one can hurt you. You just need to remember that every time they fuck with you, you fuck with them twice as hard.”

On the worst days at work, they can comfort themselves with Rolex watches, Aspen ski weekends, Gramercy Park apartments, orchestra seats, and the other perks of their profession. At a recent party attended by gay financial-world types, the payoff was palpable. Well-dressed men chattered happily as a handsome server walked around with trays of hors d’oeuvre. They discussed plans for their Hamptons summer houses and Fire Island retreats, trips to South Beach, safaris in Kenya.

One man, a tanned, dapper banker in his forties, talked cheerfully, if a tad defensively, about his life. Working on Wall Street, he said, had allowed him to see the world, meet famous people, generously donate to the causes he found important. Yes, it was true that he had to be discreet at work, but in the end, what a small price to pay.

After his third glass of champagne, he settled into the plush leather couch, and for a moment his brimming confidence seemed to shrink. He acknowledged that he had not had a relationship in more than five years, and that sometimes all the posturing and hiding made him sick. He talked about moving out of New York, cashing out, settling down. “I guess it’s true that in the end they buy you,” he said. “They buy your dignity. And the worst thing is, you happily sell it to them.” Thinking it through, he remained silent for about a minute, until a thought seemed to perk him up again. “I guess,” he said, smiling, “people have sold their self-respect for a lot less than $3 million a year.”

Reference