The dance scene owes much to gay culture…

Earlier this year, Lithuanian producer Ten Walls was riding on a wave of global love with his big-room smasher ‘Walking With Elephants’. Then, in a strange move, which in the future will be seen as a case study for career sabotage, he wrote a homophobic rant on his Facebook page.

The post compared homosexuals to paedophiles and referred to the LGBT community as “another breed”. His bigotry sent chills down the spine of anyone with an open mind and memories of less liberal times.

For many, reading such hateful views can be frightening.

While the UK’s an apparent bastion of tolerance, Stonewall’s national figures suggest eight in 10 LGBT people have been verbally abused or harassed and one in 10 has been physically assaulted. There might be gay characters in Hollyoaks, but it’s not all rainbows out there. LGBT acceptance is still fairly fragile and far from certain outside city centres.

TAPESTRY

Ten Walls’ comments revealed an embarrassing lack of historical perspective. House music (and all its subsequent forms) wouldn’t be the phenomenon it is today if it wasn’t for the major contribution from an underground scene on both sides of the Atlantic that was black, queer and fabulous.

Frat boys, R&B stars and TOWIE types are fist-pumping to EDM with a gusto that’s cheering, but also quite depressing. The musical narrative that led us to where we are today began over thirty years ago. Electronic music emerged from a scene that was alternative, diverse and mostly, very, very gay. Ten Walls? You listening at the back?

As with any cultural phenomenon, there are many threads which merge to make a fine tapestry. The LGBT contribution to the dawn of house isn’t the whole story, but it’s the backbone, glitter and colour that often gets overlooked. The unsung influence of gay culture may not stem from conscious discrimination, but when a major contribution isn’t celebrated, that oversight can allow homophobia to flourish.

The roots of today’s dance music are definitely disco — be that EDM, dubstep, house or trance. Disco spawned the driving kick-drum and epitomised the escapism, abandon and release that should be at the heart of any decent dance tune.

David Mancuso’s parties at The Loft in NYC were the ground zero of the disco movement. In 1973 Vince Aletti wrote a piece for Rolling Stone documenting the covert scene of, “After-hours clubs and private lofts open on weekends to members only — a hard-core dance crowd — blacks, Latins, gays.”

The much missed DJ Tallulah (1948-2008) span at Studio 54 in New York, but in 1974 took London by storm as the resident DJ at Bang on Charing Cross Road. When asked about dance music culture, he sniffed: “The rave lifestyle of Ibiza in the late ‘80s was just a vanilla version of the New York gay lifestyle of the ‘70s.”

NON STOP ECSTATIC DANCING

In 1981, when ‘house’ was something you might shout while playing bingo, but certainly wasn’t a ‘feeling’ or a genre, Marc Almond from Soft Cell pioneered a poetic take on queer sex, low life and ecstasy. Yes, you read that right — 1981.

The band mortified middle England with ‘Non Stop Erotic Cabaret’, then in ’82 forged electronic mixes and MDMA approval with ‘Non Stop Ecstatic Dancing’, a remix album that featured a rap from Cyndi Ecstasy, a notorious New York MDMA dealer.

Almond is a deserving national treasure now, but back then, he attracted vicious savaging from both the press and public. The mainstream may have been hating on him, but Marc was ‘loved up’ long before Ibiza became a byword for Mediterranean indulgence.

DISCO DECADENCE

Marc Almond wasn’t the only one to enjoy chemical hedonism in NYC and bring back the vibes (and drugs) to the grey shores of England. Promoter Steve Swindells recalls visiting Paradise Garage and Studio 54: “I got to visit the ultimate VIP room, the manager’s office, and yes *sniff*, it’s all true!

What many people don’t know is that there was a heaving, largely gay orgy in the capacious basement every night! Paradise Garage, however, was something else entirely. That vast space with its incredible soundsystem! The largely gay, black and Hispanic crowd were totally off-their-tits — mostly on Quaaludes (known as ‘Ludes).”

Inspired by Paradise Garage, Swindells returned to London in ’82 and opened The Lift at the Gargoyle club. Susan Sarandon attended the opening bash and the club was immortalised as ‘The Shaft’ by Booker Prize winner Alan Hollinghurst in his first novel The Swimming Pool Library.

The Lift nodded towards New York’s disco palaces, but its roots were in South London’s largely black, illegal, gay house parties (or ‘Blues’ as they were known). Lift resident DJ Mel, of the KCC Sound System, found his feet at those illicit Blues parties and is regularly cited as one of London’s foremost black and proud DJs.

GIVE ME SOME MOORE

In 1983 Philip Sallon opened the Mud Club, a Friday nighter, with DJs Tasty Tim and Jay Strongman. Mark Moore launched his DJ career at the club, when he was promoted from carrying Tim’s records to stepping in when she took a night off.

The club’s clientele were a mix of queens, b-boys and fashionistas. The music was equally eclectic, ranging from hip-hop to show tunes and ‘trash’ — such as the theme tune from kids TV fave Rupert The Bear. The more leftfield and cheesy the tunes were, the crazier the crowd went.

Jeremy Norman opened Heaven in 1979 and by the early ‘80s, it was at the top of its game, giving gay London an epic club that rivalled anything New York (or the world) had to offer. Thursday nights were Asylum, run by Kevin Millins and hosted by Laurence Malice (the infamous Trade supremo).

Asylum and its successor, Pyramid, may get overlooked as acid house incubators, possibly because the crowd didn’t look like the smiley-faced, baggy-togged ravers that came to define the Second Summer Of Love. At Pyramid, die-hard leather clones inhaled amyl nitrate with nuclear goths and industrial transvestites. It was dark, cruisey and very weird. Heaven on any night could be unhinged and alarming, but it really climbed the walls midweek.

Mark Moore became resident on the main floor and as the mid ‘80s approached, he was characteristically experimental: “We were playing a lot of alternative electronic stuff; Cabaret Voltaire, Yello, DAF, New Order. They slotted in with the imports that were coming from Chicago and Detroit. We didn’t know what they were. It was just an extension of the electronic stuff I was already playing. Nobody settled on ‘house music’ for quite a while.”

BLACK, QUEER AND ACID

Those imports from Chicago were largely produced by and made for the city’s queer and black clubs, such as The Warehouse and The Music Box — where DJs like the late Frankie Knuckles were making a name for themselves. Initially, the tunes were a fusion of Italo, Euro-pop and funk. When producers started dabbling with the Roland TR-303 synthesiser, a style emerged that was sparser, spacier and was later dubbed ‘acid house’.

At Pyramid, the freaks ruled and nervy straight boys grudgingly gave respect to the cutting-edge sounds, with their backs firmly against the wall. It was a twitching, bitching melting pot, but it wasn’t loved by everyone. The commercial LGBT scene wasn’t entirely enamoured by the club’s electro beats and Dadaist fashions. Mark Moore regrets mentioning this schism.

“The mistake I made was recounting how the mainstream gay scene kind of rejected it — calling us the ‘black sheep’. In the eyes of most journalists, that makes it seem like it wasn’t that important. But everyone who went to those clubs has told me off for that. Of course it was important. It was JUST as important as the 30 people who saw the Sex Pistols in Manchester. It was MORE than 30 people. It was over 1,000 people, packing out at Heaven, midweek.”

As someone who attended Pyramid religiously, I can confirm that it was both seminal and heaving. My heroic 90-minute nightbus journey home, followed by a half-hour stagger through sleeping suburbia, was always worth the pain of crawling into bed at dawn, covered in glitter, fag-ash and saliva.

Attracting a much smaller clique, but equally wacky, was Leigh Bowery’s Taboo at Maximus in Leicester Square, launched in 1985. Immortalised in Boy George’s musical of the same name and hailed by the style crowd, there’s a chemical aspect of the club that’s often forgotten.

“It was very hi-energy and Italo,” remembers Mark Moore. “But what made it beautiful were Jeffery Hinton’s mix tapes. They were completely druggy and amazing. It was definitely the first place in London where there was mass ecstasy taking.”

Regulars at Taboo, such as Hot Gossip’s Mark Tyme and DJ Mark Lawrence (RIP) would spend hours at home perfecting synchronised dance routines to perform at the club. There was also a fad for formation ‘falling down’.

Basically, all those on the dancefloor would collapse in unison, often as a response to the floorshow. Taboo was demented, messy, short-lived and quite elite, but people have said the same of Danny Rampling’s Shoom. And that was two years later.

PROTO-RAVERS

Luke Howard is resident DJ at Horse Meat Disco and played Queer Nation for 14 years. He agrees that the gays were raving long before it had a name.

“Pre acid house/rave culture, you’d hear house music in many gay clubs in London. The DJ at the Prince Of Wales in Brixton would play house tracks like ‘House Nation’, and the first time I heard ‘House Music Anthem’ by Marshall Jefferson was at a venue called Traffic on York Way [in Kings Cross].

I went straight to Groove Records and bought a copy on import the next day. The biggest night that played loads of house music was Pyramid at Heaven where Mark Moore and Colin Faver were residents.”

On a less alternative tip, but fiercely serving the LGBT black community, was Jungle at Busby’s on Charing Cross Road.

The Monday nighter ran from ’83-86 and again, Steve Swindells was at the helm. He ponders its influence: “The DJs were Colin Faver (Kiss FM) and Fat Tony (his first regular DJ gig — I think he was 15!). In ‘86 they started drip-feeding a new genre of US imports in with the otherwise largely black music they were playing. Jungle hosted, I believe, the first-ever house music PA in London. That was Darryl Pandy singing Farley Jackmaster Funk’s ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’. The crowd went crazy.”

MY HOUSE IS YOUR HOUSE

Mark Moore became quite militant in his refusal to play anything BUT house. This took shape in ’87 at Planet Love at The Fridge, run by Nicky Trax.

Moore declared a musical war: “We put a sign on the door saying, ‘We play house music — if you don’t like it, please don’t come in’. There were a lot of locals who wanted to hear rare groove and we used to worry they’d come in and shoot us. So we put that warning on the door. And two years later those records DID become classics.”

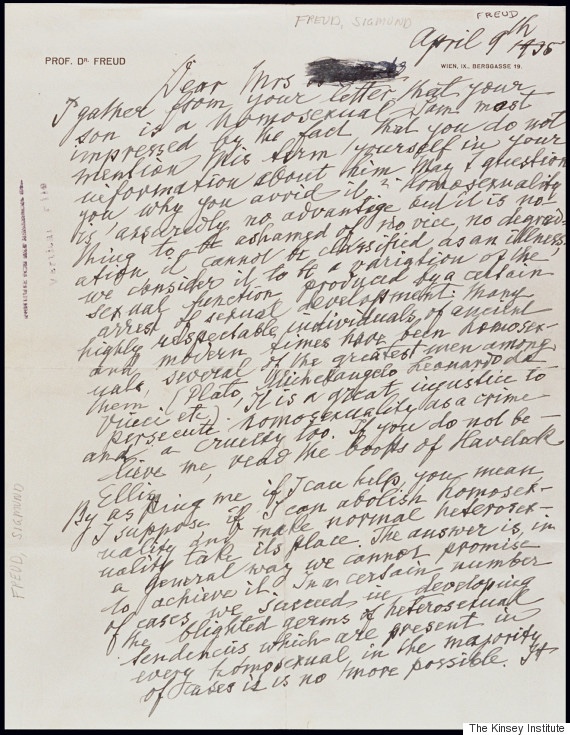

There’s another aspect to this story that may explain why the LGBT contribution to UK house isn’t documented in a detailed fashion. As the Second Summer Of Love dawned in ’88, the UK gay scene was in major crisis and London was the epicentre of this battle. HIV/AIDS was cutting a swathe through our community, instilling tabloid panic, a rise in homophobia and widespread fear.

In 1988, we were nursing loved ones, fighting bigotry, attending floods of funerals and trying to stay alive and chipper. The edgiest innovators from a wild period of creativity were dying, or had turned to activism in response to a grim pandemic and a ruthless Tory government.

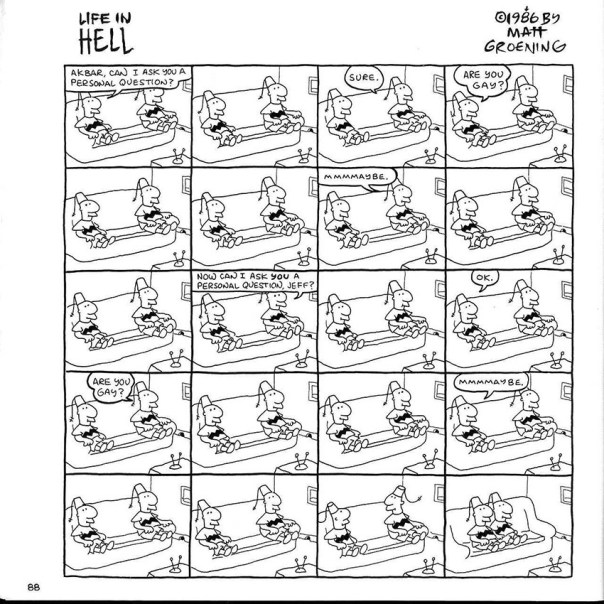

The age of consent for same-sex sexual activity was 21, so at this time, I was effectively jail bait. My boyfriends faced prison if we were caught together. The absurd laws didn’t stop passion, or inhibit love, but it was far from agreeable.

Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 prohibited local authorities in England and Wales from “promoting” homosexuality. It also labelled gay family relationships as “pretend”. The Second Summer Of Love emerged against this background of oppression and prejudice.

The gays had been integral to getting the house party started, but by late ‘88, the community’s focus had switched from MDMA to AZT and HIV. Quite frankly, we were busy.

We lost a lot of people. AIDS savaged clubland like a rusty scythe. DJs, drag stars, artists, designers and go-go boys either died or went below the radar.

Of course, HIV didn’t single out creatives, but the clubs were fuelled and populated by that crowd. The club kids and older gay men who’d ruled discos in the ‘70s suddenly became thin on the ground. Between ’88 and ’93, I was either raving or grieving.

Or both. I should have been studying, but I spent more time lost in dry ice than in the books on the syllabus. On more than one occasion, I dropped ecstasy while attending a funeral wake. It wasn’t disrespectful. On the contrary, the common refrain, as we gurned over yet another coffin, was: ‘It’s what they would have wanted’.

SECOND SUMMER OF LOVE

The party continued. It always does, but it was really picking up on the illegal rave scene. The energy that sparked the flames of house music in subversive gay clubs exploded elsewhere as the Second Summer Of Love (1988-’89). If you weren’t dead or too sad to pop pills, you threw yourself into the cultural phenomenon that was loved-up, initially optimistic but totally anti-establishment.

James Horrocks, co-creator of React Records, remembers the shift in thinking. “More young gay people were looking for something new and more vibrant, and had already frequented fashion-orientated clubs that embraced the mixed message,” he recalls.

“This was fully realised with the arrival of acid house and E-culture. Vast swathes of the scene migrated to warehouses to join the raving masses. It was such a sweeping change for the LGBT scene, it was forced to throw out the rule-book.”

My personal party habits in ’88 reflected the uncertain mood of the times. My straight mates (God love ‘em) were cracking AIDS jokes, dissing ‘bum bandits’ and dropping acid while dancing on the forecourt at Heston Services. We were a gang of sorts, our catchphrase being, ‘We put the E into Ealing’.

This much was true. We were regulars at a club called Haven Stables in Ealing (where Brandon Block got started). When the club threw us out, we’d dance on the green outside, to the bemusement of daytime shoppers and commuters. Despite all the pill-fuelled love and empathy, I still didn’t feel happy ‘coming out’ to them. In fact, I was terrified they’d find out.

With my straight mates, we’d go to Nicky Holloway’s Trip at The Astoria, Paul Oakenfold’s Spectrum at Heaven and the RiP raves in Clink Street. On the sly and on my own, I’d let my hair down at the queer parties, such as Jimmy Fox’s Daisy Chain (The Fridge, Brixton), Troll (The Soundshaft) and Pyramid. It was a dual life of double-dropping and downlow habits. Occasionally, the two lives would collide under the lasers. When I saw queens at the big, straight raves, I’d steer clear and spurn recognition — the dancing gay Judas with dilated pupils.

MADCHESTER

My dwindling studies took me to Liverpool in ‘89 and much to my southern surprise, the north was embracing rave culture with characteristic passion. Liverpool took to rave in a big way, but Manchester pipped it to the post and became the darling of the music press. ‘Madchester’ was thrilling.

The city buzzed off its renaissance, but it wasn’t just the scallies and the wide-boys getting ‘on one’. Manchester boasted a booming gay scene that was cocky, hip and ready to ‘ave it ‘til dawn. As it was a short drive from Liverpool, that’s where yours truly spent most weekends.

DJ Dave Kendricks explains the city’s LGBT heritage: “Manchester’s musical history is full of gay signifiers, from Pete Shelley singing ‘Ever fallen in love with someone you shouldn’t have?’ to New Order openly imitating the sound of Bobby O on ‘Blue Monday’.”

The No.1 Club on Central Street was a small carpet-and-chrome club that became THE queer rave destination in Manchester. Tim Lennox played feel-good piano house on a quadrophonic sound system, to a rocking clan of devotees.

Previously scared to come out to my straight mates, the cat was now out of the bag and the No.1 was where I took the boys. One night, a bunch of them cheered when I snogged a drug-dealing gangster. I couldn’t have been happier. Not only had they accepted my sexuality, they were applauding it. Times were a-changing and E was fuelling the evolution.

I paid £25 for an acid tab at Mike Pickering’s Nude at The Haçienda and while it was a boss night, when Paul Cons opened Flesh at The Haçienda in 1991, THAT was mind-blowing.

Resident DJ at Flesh, Dave Kendricks also remembers it fondly.

“That monthly gay night at The Haçienda was the greatest night I ever played. It was raucous, hedonistic, totally Northern and felt like a city turning its back on prejudice, towards acceptance, in the most thrilling way.

Just a few years before, Manchester’s chief of police James Anderton said the gay community was ‘swimming in a cesspit of its own making’ after he raided the gay club, Rockies. It was a direct reference to AIDS. Flesh was the biggest fight-back to that.”

I used to get so excited at the prospect of going to Flesh, I couldn’t eat for two days prior to the event. The club ran a coach from Liverpool to Flesh and back again. It was a demented mess on wheels. God-knows what the driver made of the transvestites in K-holes and topless lesbians dancing on the seats.

As a fledgling DJ, I’d set up decks and a soundsystem at home, in Toxteth. On more than one occasion, when the coach returned from Flesh, it would stop outside my home on Elwy Street and the tripping, screaming contents of the bus would pile into my cottage and the party would continue for days.

The epic post-Flesh socials in my Liverpool latty were known as Club Lovestretch. We painted the house in UV graffiti, installed black lights and removed the bannisters, so people could rave on the stairs. I was living in Liverpool, partying in Manchester and returning to London at every opportunity. I was very busy.

QUEER NATION

In 1990, Patrick Lilley opened Queer Nation at Covent Garden’s Gardening Club. “I’d run the first soulful house and garage club in the UK, High On Hope at Dingwalls,” Lilley tells DJ Mag. “Queer Nation was just the mutated gay version. For the authentic black heritage of house (the music that sees no colour), there’s no comparison or competition for QN. We came straight from the founding fathers.”

The brilliant Luke Howard and Princess Julia were the resident DJs at Queer Nation and I spent many a Sunday night in Patrick’s VIP ‘cupboard’ with his hash pipe and secret booze stash. Due to the Sunday trading laws, there was no alcohol served after 10pm, but where there’s a will…

While Queer Nation kept it funky, other London LGBT clubs were picking up the pace and breaking ground with tougher sounds. “React (myself and Thomas Foley and later Steven React) took over promoting Garage at Heaven and Troll at The Soundshaft in the summer of 1990,” James Horrocks tells DJ Mag.

“The New York house and Detroit techno we played at Garage and Troll had morphed into a much harder sound — a mix of techno and new beat. It immediately found popularity on the scene and along with the soulful house and garage sound of New York, became the soundtrack of our lives.”

Blu Peter, resident DJ at Garage, enjoyed success as both a DJ and a producer. “Garage integrated gay and straight crowds and became more about the music and less about the sex at the end of the night!” he tells DJ Mag.

“The ‘Reactivate’ series produced tunes that were tried and tested there. Mrs Wood and I were the first international DJs to play South Africa after Apartheid, and also after the hand-over in Hong Kong. Both gigs were massive honours.”

ALL-NIGHT BENDER

In 1990, another club launched in London that made the debauchery of Studio 54 appear tame and a bit lightweight. Laurence Malice (and Tim Stabler) launched Trade at Turnmills and unlike any club before, it started at 4am on a Sunday morning.

Plugged as the ‘original all-night bender’, the club stayed open ‘til way past Sunday lunchtime and was a deranged cocktail of sex, drugs and house music. Trans beauties, supermodels, international DJs, muscle boys, East End gangsters and A-list celebrities rubbed shoulders and partied en masse, every week, like their lives depended on it. It was full tilt at 8am.

It’s impossible to convey both the lunacy of the club and the obsessive allegiance of its regulars. Entry wasn’t guaranteed, even if you were gay. The door policy was vague, but sturdy: “You don’t have to be gay or a member to get in, but your attitude and look will count.”

Me and my mates used to party at The Curzon, Jody’s or Quadrant Park in Liverpool, then drive all the way to Farringdon as dawn approached. We’d stagger out of Trade at 2pm, then drive all the way back to Liverpool. Some of those journeys, swerving along the motorway, were a little bit scary.

Trade launched the DJ careers of a number of big players who’re still rocking it today. The original line-up was Martin Confusion, Daz Saund, Trevor Rockliffe, Smokin’ Jo and Malcolm Duffy. This stellar cast was later joined by ‘Tall’ Paul Newman, Alan Thompson, Steve Thomas, Pete Wardman, Ian M, The Sharp Boys, Fat Tony and Fergie.

The most celebrated Trade DJ remains the late, great Tony De Vit (1957 –1998). Tony’s mixing skills and ability to spin an overwhelming symphony of hard house led to him being venerated like a god.

Tragically, Tony died at 40, due to AIDS-related bronchial failure. One only has to listen to his single ‘Burning Up’, or his remix of ‘Hooked’ by 99th Floor Elevators to get an idea of his sound. However, to really understand De Vit’s magic, you had to be there, under the lasers, as his galloping wall of sound inspired joy, disbelief and amazement.

I moved back to London after (barely) completing my studies, and after a chance encounter with Laurence Malice, wound up working on the door of Trade for five years. I’d already decided it was the greatest queer club in the world, long before I became part of its rude family.

My enthusiasm for Trade’s hedonistic spirit never waned. I’d finish on the door at 10am, then get on the dancefloor ‘til the club shut that afternoon. Like Ice-T says in the NRG classic, which became a Trade anthem, ‘He Never Lost His Hardcore’.

DTPM

Lee Freeman’s Sunday afternoon party started in ’93, as a post-Trade knees-up, at an Italian restaurant in Holborn called Villa Stefano. In order to get round the Sunday licensing laws, an enormous buffet would greet the still-buzzing gay ravers as they trooped in from Turnmills. I never saw anybody eat anything, except for the odd pill.

Over the years, it moved, first to Bar Rumba, then The End, and finally, it did a major eight-year stint at Fabric on Sunday nights. Many of DT’s residents, such as Smokin’ Jo, Alan Thompson and Steve Thomas, were regular Trade DJs, but DTPM honed a funkier, deeper groove which helped establish the club’s unique brand.

I had my very own pillar at The End (in between the two dancefloors, next to the toilets), where you could find me, every Sunday, grinning and clinging onto it for dear life.

WOMEN IN THE HOUSE

The Fridge in Brixton hosted the first huge, women-only club night Eve’s Revenge in the ‘80s, followed by Venus Rising in the ‘90s. It regularly attracted over 1300 lesbian clubbers. A special mention must go to the awesome Vicky Edwards, who span at Jungle, Venus Rising and Bad at the Soundshaft. She’s still an excellent DJ.

DJ Smokin’ Jo used to sashay through Trade with a hunk hefting her record box, and the crowd would gawp at her sass and beauty. More importantly, she’d take to the decks and totally rock the place. “Trade gave a platform to that real US house style of music,” she tells DJ Mag. “It felt cutting edge and of course, it brought techno and harder sounds to the forefront.”

Jo was a regular in DJ Mag in its early days and her relationship with Skin from Skunk Anansie proved a powerful and gorgeous fusion of rock and house sovereignty. Hearing Skin rap over Jo’s DJ set at the DTPM tent at Gay Pride in Brockwell Park remains, for me, a gobsmacking and pivotal point in black girl power.

One could argue that female DJs suffered less sexism in LGBT clubs than elsewhere, but lesbian raving really hit a peak when clubs such as Pumpin’ Curls and Kitty Lips shook up London in the mid ‘90s. “We, Vikki Red and myself, were DJs first and foremost,” Queen Maxine tells DJ Mag. “Individually, we played to varying audiences over the world for many years.

We set out to offer something unique, yet boutique; a forward-thinking space for women (of all sexual persuasions and their gay male friends as guests) who appreciated the harder side of dance music and wanted a space without getting ‘put on’ by straight guys.

“It certainly worked. We promoted two very well attended and respected nights; Pumpin’ Curls and then Kitty Lips. These clubs ran alongside Trade at Turnmills, as the little sister club. Laurence Malice was very supportive and helped open many doors for us.

The secret to our success was keeping ahead of the pack and offering something different and daring. Because of this approach, we were able to attract a very diverse crowd, who believed they were a part of something that hadn’t been done before.”

In ’94, Suzie Kreuger arrived in London. With her NYC Clit Club experience, she launched the notorious Fist. A woman, promoting a gay fetish club, was a novelty in itself. The real revolution was that Fist welcomed S&M lesbians, who joined the leather men under one roof, all united in a passion for kink, pills and techno.

It was very queer, often shocking and musically brutal. Prior to Fist, I’d never seen lesbians having sex or watched live shows that were so graphic, punters fainted, fled or vomited on a regular basis. Lesbian techno mistress EJ Doubell span fearsome sets that only added to the demonic and highly-charged vibe.

MONDAY MORNING

Trade, Garage and Fist weren’t the only LGBT clubs serving up nu techno and ‘hardbag’. The truly wayward headed to FF at Turnmills on Sunday nights. Launched in ’89 by Mark Langthorne and Nicholas Timms, it was a dark and uncompromising night that featured Suzie Kreuger on the door and a crowd who were happy to be bang at it ‘til 5am Monday morning.

Mrs Wood and Blu Peter were the celebrated residents. Having spent my Sunday morning working at Trade, FF was where yours truly went to let off steam and feel the joy and terror of manic techno and hard trance.

The club wasn’t very welcoming to those who weren’t LGBT, and it certainly wasn’t for the faint hearted. The creative team behind FF also produced a satirical fanzine (also called FF) that was militantly gay and so near the knuckle, it eventually got shut down by a law suit.

Asked about FF, Blu Peter admits to, “Special and often bizarre memories. On the whole it was a night when you could expect anything. The audience loved to be pushed and challenged. I aspired to play there above anywhere else. The legacy is that people still talk about it, though it ended 20 years ago.”

While Peter is right, it seems that straight, white, mainstream culture prefers to tell another account when it comes to electronic music. Dave Kendrick, DJ at Flesh, isn’t surprised at the selective story telling. “Unless you’re talking about hairdressing, airline stewarding or musical theatre, the LGBT contribution is overlooked in almost all UK cultures,” he says.

“We only reached full legal equality [in the UK] last year and within that, LGBT people will always be a minority. The dialogue about what we’re due is only just beginning. You have to shout to be heard when you’re in the minority, but that doesn’t mean the amazing gay nightlife culture incubated in the British gay night-time isn’t worth shouting about. It’s an inspirational story of underground culture directly informing the mainstream.”

It’s perplexing to note that sexual diversity appears to have almost vanished from electronic music media and the wider conversation. Largely straight, white middle class crowds are embracing a genre that was birthed by working class, queer, black and Latin people over three decades ago. The young seem especially ignorant of the struggles those communities endured then and, in many parts of the world, continue to experience now.

ROOTS AND RIGHTS

For a new generation, whose first experience of house music might be Avicii or David Guetta, this seems especially pertinent as they enjoy the party, but are blind to LGBT battles being fought in places like Russia or the Middle East.

Twenty years ago in the USA, it was rare to hear house music except in black or LGBT clubs and on very few radio stations. Currently, there’s a colossal mainstreaming of dance music, not just in America, but worldwide. It’s brilliant that these newcomers, commercially defined by pumped up boys and blonde party girls, get to feel the shared joys of house music. But it’s all a bit hollow if they don’t appreciate the roots.

Strides have been made and for many in the wider LGBT community, life is less fearful than it was 30 years ago. However, if ‘Music Is the Answer’, one can’t help but wonder what the question was? One thing’s for certain, as electronic music continues to dominate popular culture, we’d do well to remind ourselves of the diversity, political struggle and sheer queerness that was so fundamental to the very DNA of dance music. Joe Smooth once sang, ‘Brother, sisters/One day we will be free/From fighting, violence/People crying in the street’.

Top tune, lovely message, but we’re not there yet.

Reference