How the Germans invented gay rights—more than a century ago.

How the Germans invented gay rights—more than a century ago.

Magnus Hirschfeld and two cross-dressers, outside the Institute for Sexual Science.Courtesy Photo Hirschfeld / Voilà / Gallimard

On August 29, 1867, a forty-two-year-old lawyer named Karl Heinrich Ulrichs went before the Sixth Congress of German Jurists, in Munich, to urge the repeal of laws forbidding sex between men. He faced an audience of more than five hundred distinguished legal figures, and as he walked to the lectern he felt a pang of fear. “There is still time to keep silent,” he later remembered telling himself. “Then there will be an end to all your heart-pounding.” But Ulrichs, who had earlier disclosed his same-sex desires in letters to relatives, did not stop. He told the assembly that people with a “sexual nature opposed to common custom” were being persecuted for impulses that “nature, mysteriously governing and creating, had implanted in them.” Pandemonium erupted, and Ulrichs was forced to cut short his remarks. Still, he had an effect: a few liberal-minded colleagues accepted his notion of an innate gay identity, and a Bavarian official privately confessed to similar yearnings. In a pamphlet titled “Gladius furens,” or “Raging Sword,” Ulrichs wrote, “I am proud that I found the strength to thrust the first lance into the flank of the hydra of public contempt.”

The first chapter of Robert Beachy’s “Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity” (Knopf) begins with an account of Ulrichs’s audacious act. The title of the chapter, “The German Invention of Homosexuality,” telegraphs a principal argument of the book: although same-sex love is as old as love itself, the public discourse around it, and the political movement to win rights for it, arose in Germany in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This message may surprise those who believe that gay identity came of age in London and New York, sometime between the Oscar Wilde trials and the Stonewall riots. The brutal repression of gay people during the Nazi period largely erased German gay history from international consciousness, and even from German memory. Beachy, a historian who teaches at Yonsei University, in Seoul, ends his book by noting that Germans hold gay-pride celebrations each June on what is known as Christopher Street Day, in honor of the street where the Stonewall protest unfolded. Gayness is cast as an American import.

Ulrichs, essentially the first gay activist, encountered censorship and ended up going into exile, but his ideas very gradually took hold. In 1869, an Austrian littérateur named Karl Maria Kertbeny, who was also opposed to sodomy laws, coined the term “homosexuality.” In the eighteen-eighties, a Berlin police commissioner gave up prosecuting gay bars and instead instituted a policy of bemused tolerance, going so far as to lead tours of a growing demimonde. In 1896, Der Eigene (“The Self-Owning”), the first gay magazine, began publication. The next year, the physician Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, the first gay-rights organization. By the beginning of the twentieth century, a canon of gay literature had emerged (one early advocate used the phrase “Staying silent is death,” nearly a century before aids activists coined the slogan “Silence = Death”); activists were bemoaning negative depictions of homosexuality (Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice” was one target); there were debates over the ethics of outing; and a schism opened between an inclusive, mainstream faction and a more riotous, anarchistic wing. In the nineteen-twenties, with gay films and pop songs in circulation, a mass movement seemed at hand. In 1929, the Reichstag moved toward the decriminalization of homosexuality, although the chaos caused by that fall’s stock-market crash prevented a final vote.

Why did all this happen in Germany? And why is the story not better known? Beachy, focussing on Berlin’s social fabric, doesn’t delve too deeply into larger philosophical questions, but the answers are hardly elusive. The inclination to read German history as an extended prelude to Nazism—the “heading for Hitler” narrative—has tended to exclude countervailing progressive forces, especially those of the Wilhelmine period, from 1871 to 1918. The towering legacy of German idealism and Romanticism, which helps to explain why the gay-rights movement took root in Germany, has itself become somewhat obscure, especially outside the German school system. And so we are surprised by the almost inevitable. Nowhere else could a figure like Ulrichs have made his speech, and nowhere else would cries of “Stop!” have been answered by shouts of “No, no! Continue, continue!”

In Leontine Sagan’s 1931 film “Mädchen in Uniform,” the first sympathetic portrayal of lesbians onscreen, a boarding-school pupil named Manuela plays the title role in a school production of Friedrich Schiller’s 1787 play “Don Carlos,” an emblematic Romantic tale of forbidden love and resistance to tyranny. “A moment passed in paradise is not too dearly bought with death,” Manuela declaims onstage, conveying Don Carlos’s love for his stepmother. Afterward, fortified by punch, Manuela announces her love for one of her teachers, precipitating a scandal. The episode suggests the degree to which the German cultural and intellectual tradition, particularly in the Romantic age, which stretched from Goethe and Schiller to Schopenhauer and Wagner, emboldened those who came to identify themselves as gay and lesbian. (“Schiller sometimes writes very freely,” an elderly woman worriedly observes in Sagan’s film.

Close to the heart of the Romantic ethos was the idea that heroic individuals could attain the freedom to make their own laws, in defiance of society. Literary figures pursued a cult of friendship that bordered on the homoerotic, although most of the time the fervid talk of embraces and kisses remained just talk. But the poet August von Platen’s paeans to soldiers and gondoliers had a more specific import: “Youth, come! Walk with me, and arm in arm / Lay your dark cheek on your / Bosom friend’s blond head!” Platen’s leanings attracted an unwelcome spotlight in 1829, when the acidly silver-tongued poet Heinrich Heine, insulted by anti-Semitic remarks that Platen had lobbed at him, satirized his rival as a womanly man, a lover of “passive, Pythagorean character,” referring to the freed slave Pythagoras, one of Nero’s male favorites. Heine’s tone is merrily vicious, but he inserts one note of compassion: had Platen lived in Roman times, “it may be that he would have expressed these feelings more openly, and perhaps have passed for a true poet.” In other words, repression had stifled Platen’s sexuality and, thus, his creativity.

Gay urges welled up across Europe during the Romantic era; France, in particular, became a haven, since statutes forbidding sodomy had disappeared from its books during the Revolutionary period, reflecting a distaste for law based on religious belief. The Germans, though, were singularly ready to utter the unspeakable. Schopenhauer took a special interest in the complexities of sexuality; in a commentary added in 1859 to the third edition of “The World as Will and Representation,” he offered a notably mellow view of what he called “pederasty,” saying that it was present in every culture. “It arises in some way from human nature itself,” he said, and there was no point in opposing it. (He cited Horace: “Expel nature with a pitchfork, she still comes back.”) Schopenhauer proceeded to expound the dubious theory that nature promoted homosexuality in older men as a way of discouraging them from continuing to procreate.

Not surprisingly, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs seized on Schopenhauer’s curious piece of advocacy when he began his campaign; he quoted the philosopher in one of his coming-out letters to his relatives. Ulrichs might also have mentioned Wagner, who, in “Die Walküre” and “Tristan und Isolde,” depicted illicit passions that many late-nineteenth-century homosexuals saw as allegories for their own experience. Magnus Hirschfeld, in his 1914 book “The Homosexuality of Men and Women,” noted that the Wagner festival in Bayreuth had become a “favorite meeting place” for homosexuals, and quoted a classified ad, from 1894, in which a young man had sought a handsome companion for a Tyrolean bicycling expedition; it was signed “Numa 77, general delivery, Bayreuth.” Ulrichs had published his early pamphlets under the pseudonym Numa Numantius.

Encouraging signals from cultural giants were one thing, legal protections another. The most revelatory chapter of Beachy’s book concerns Leopold von Meerscheidt-Hüllessem, a Berlin police commissioner in the Wilhelmine period, who, perhaps more than any other figure, enabled “gay Berlin” to blossom. Meerscheidt-Hüllessem’s motivations remain unclear. He was of a “scheming nature,” a colleague noted, and liked nothing better than to gather masses of data on the citizenry, like a less malignant J. Edgar Hoover. His Department of Homosexuals, founded in 1885, maintained a carefully annotated catalogue of Berliners who conformed to the type. He evidently was not gay, although his superior, Bernhard von Richthofen, the police department’s president, is said to have had a taste for young soldiers. Meerscheidt-Hüllessem might have reasoned that it was better to domesticate this new movement than to let it become politically radicalized or overtaken by criminal elements.

For whatever reason, Meerscheidt-Hüllessem took a fairly benevolent attitude toward Berlin’s same-sex bars and dance halls, at least in the better-heeled parts of the city. He was on cordial terms with many regulars, as none other than August Strindberg attested in his autobiographical novel “The Cloister” (1898), which evokes a same-sex costume ball at the Café National: “The Police Inspector and his guests had seated themselves at a table in the centre of one end of the room, close to which all the couples had to pass. . . . The Inspector called them by their Christian names and summoned some of the most interesting among them to his table.” Meerscheidt-Hüllessem and his associates also showed solicitude for gay victims of blackmail, and went so far as to offer counselling. In 1900, the commissioner wrote to Hirschfeld expressing pride that he had saved people from “shame and death”: blackmail and suicide. A week later, in a grim irony, this enigmatic protector killed himself—not on account of his homosexual associations but because he was exposed as having taken bribes from a millionaire banker accused of statutory rape.

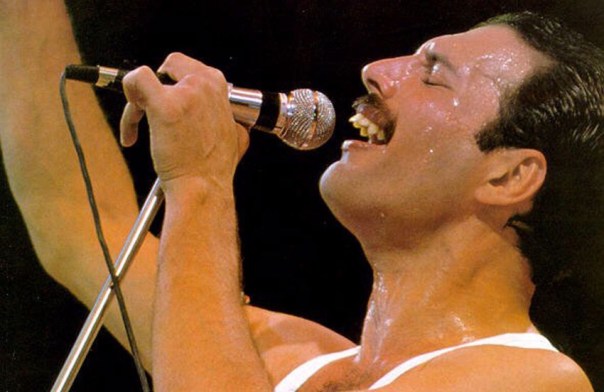

Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Committee probably could not have existed without Meerscheidt-Hüllessem’s tacit approval. (The commissioner was invited to the organization’s first meeting, although he probably did not attend.) Hirschfeld, who was born in 1868, a year after Ulrichs’s speech in Munich, began his radical activities in 1896, publishing a pamphlet titled “Sappho and Socrates,” which told of the suicide of a gay man who felt coerced into marriage. The next year, Hirschfeld launched the Committee, and soon afterward reprinted Ulrichs’s writings. Building on Ulrichs’s insight that same-sex desire was a congenital trait, Hirschfeld developed a minutely variegated conception of human sexuality, with a spectrum of “sexual intermediaries” appearing between the poles of the purely male and the purely female. He felt certain that if homosexuality were understood as a biological inevitability then the prejudice against it would disappear. “Through Science to Justice” was his group’s motto.

Beachy is candid about Hirschfeld’s limitations. His scientific work blended research and advocacy to an uncomfortable degree, and some of his confederates employed suspect methodologies. (One associate’s study of male prostitution in Berlin involved sleeping with at least one hustler.) But Hirschfeld’s knowledge of sexuality was vast, and Beachy has several incisive pages comparing him favorably to Sigmund Freud, whose influence was, of course, far greater. Freud rejected the congenital hypothesis, believing homosexuality to be a mutation of childhood development. Although Freud professed sympathy for gay people, American psychoanalysts later fostered the destructive notion that homosexuality could be cured through therapy. Freud was grandly systematic in his thinking; Hirschfeld was messily empirical. The latter got closer to the intricate reality of human sexuality.

Hirschfeld had enemies in Berlin’s gay scene. His interest in effeminacy among homosexual men, his attention to lesbianism, and his fascination with cross-dressing among both gay and straight populations (he coined the word “transvestism”) offended men who believed that their lust for fellow-males, especially for younger ones, made them more virile than the rest of the population. Being married to a woman was not seen as incompatible with such proclivities. In 1903, the malcontents, led by the writers Adolf Brand and Benedict Friedlaender, formed a group called Gemeinschaft der Eigenen, or Society of Self-Owners, the name referencing a concept from the anarchist philosophy of Max Stirner. Der Eigene, Brand’s magazine, became their mouthpiece, mixing literary-philosophical musings with mildly pornographic photographs of boys throwing javelins. In the same camp was the writer Hans Blüher, who argued that eroticism was a bonding force in male communities; Blüher made a particular study of the Wandervogel movement, a band of nature-hiking youth. Nationalism, misogyny, and anti-Semitism were rampant in these masculinity-obsessed circles, and Hirschfeld’s Jewishness became a point of contention. He was deemed too worldly, too womanly, insufficiently devoted to the glistening Aryan male.

Beachy celebrates the inclusivity of Hirschfeld, who welcomed feminists into his coalition. Unfortunately, women are largely absent from “Gay Berlin.” There is no mention, for example, of the theatre and music critic Theo Anna Sprüngli, who, in 1904, spoke to the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee on the subject of “Homosexuality and the Women’s Movement,” helping to inaugurate a parallel movement of lesbian activism. Sex between women was never explicitly outlawed in imperial Germany—Paragraph 175, the anti-sodomy law, applied only to men—but lesbians found it no easier to live an open life. Employing the alias Anna Rüling, Sprüngli proposed that the gay-rights and feminist movements “aid each other reciprocally”; the principles at stake in both struggles, she wrote, were freedom, equality, and “self-determination.” References to George Sand and Clara Schumann in her speech betray an essentially Romantic vision.

This story has a melancholy epilogue, as the historian Christiane Leidinger has discovered. After Sprüngli gave her historic speech—one that may have exacerbated the split between the “masculinist” and the “sexological” factions of the gay movement, as Beachy calls them—she said nothing more about lesbianism. Instead, she fell into a conventional, even conservative, journalistic career, adopting a jingoistic tone during the First World War and concealing her radical past in the Nazi era. Perhaps she remained as openly lesbian as circumstances permitted; almost nothing is known of her later life. Yet her sudden silence suggests how quickly gains can slip away.

During the golden years of the Weimar Republic, which occupy the last chapters of “Gay Berlin,” gays and lesbians achieved an almost dizzying degree of visibility in popular culture. They could see themselves onscreen in films like “Mädchen in Uniform” and “Different from the Others”—a tale of a gay violinist driven to suicide, with Hirschfeld featured in the supporting role of a wise sexologist. Disdainful representations of gay life were not only lamented but also protested; Beachy points out that when a 1927 Komische Oper revue called “Strictly Forbidden” mocked gay men as effeminate, a demonstration at the theatre prompted the Komische Oper to remove the offending skit. The openness of Berlin’s gay scene attracted visitors from more benighted lands; Christopher Isherwood lived in the city from 1929 to 1933, enjoying the easy availability of hustlers, who, in Beachy’s book, have a somewhat exhausting chapter to themselves.

Within the gay community, the masculinist-sexological split persisted. Hirschfeld was now at the helm of the Institute for Sexual Science: a museum, clinic, and research center, housed in a handsome villa in the Tiergarten district. Widening his sphere of interests, Hirschfeld offered sex advice to straight couples, advocated more liberal divorce laws and birth control, collaborated on the first primitive sex-change operations, and generally acquired a reputation as the “Einstein of sex,” as he was called on an American lecture tour. To the masculinists, Hirschfeld appeared to be running a sexual freak show. Adolf Brand published crude anti-Semitic attacks on Hirschfeld in the pages of Der Eigene. Some of Brand’s associates were flirting with Nazism, and not just in a metaphorical sense; one of them later became the lover of Ernst Röhm, the head of the Brown Shirts.

After the First World War, a new figure entered the fray: Friedrich Radszuweit, an entrepreneur who established a network of gay publications, including the first lesbian magazine, Die Freundin. Radszuweit hoped to heal divisions and establish a true mass movement—one from which he stood to make a great deal of money. In 1923, he took the lead in forming the Human Rights League, a consortium of gay groups. Distancing himself both from Hirschfeld’s emphasis on gender ambiguity and from Brand’s predatory focus on boys, Radszuweit purveyed a vision of “homosexual bourgeois respectability,” in Beachy’s words. Fearful of displaying political bias, Radszuweit attempted to placate the Nazis, believing that they, too, would see the light.

In fact, the driving force behind the Brown Shirts was a member of the Human Rights League, as Radszuweit must have known. Röhm never made a secret of his homosexuality, and Hitler chose to overlook it; although the Nazi leader had denounced Hirschfeld and the gay movement as early as 1920, he was too dependent on Röhm’s army of thugs to reject him. In the early thirties, German leftists tried to tarnish the Nazis by publicizing Röhm’s affiliations and affairs. Brand, having finally grasped the ruthlessness of Hitler’s methods, joined the assault. “The most dangerous enemies of our fight are often homosexuals themselves,” he sagely observed. Hirschfeld, though, disliked the campaign against Röhm, and the conflation of homosexuality and Fascism that it implied. The practice of outing political figures had surfaced before—notably, during a prewar scandal surrounding Kaiser Wilhelm II’s adviser Prince Philipp zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld—and Hirschfeld had criticized the tactic, which was known as the “path over corpses.”

Nazism brought Berlin’s gay idyll to a swift, savage end. Hirschfeld had left Germany in 1930, to undertake a worldwide lecture tour; wisely, he never returned. In May, 1933, a little more than three months after Hitler became Reich Chancellor, the Institute for Sexual Science was ransacked, and much of its library went up in flames during Joseph Goebbels’s infamous book-burning in the Opernplatz. Röhm, who became less indispensable once Hitler took power, was slaughtered in 1934, during the Night of the Long Knives, the first great orgy of Nazi bloodlust. Hirschfeld, who had watched the destruction of his life’s work on a newsreel in Paris, died the next year. Brand somehow survived until 1945, when he fell victim to Allied bombs. Vestiges of Paragraph 175 lingered in the German legal code until 1994.

In the decades after the Second World War, German historiography fell under the sway of the Sonderweg, or “special path,” school, which held that the country was all but doomed to Nazism, because of the perennial weakness of its bourgeois liberal factions. Since then, many historians have turned against that deterministic way of thinking, and “Gay Berlin” follows suit: Germany here emerges as a chaotic laboratory of liberal experiment. Beachy’s cultivation of the “other” Germany, heterogeneous and progressive, is especially welcome, because the Anglophone literary marketplace fetishizes all things Nazi. Appearing in the same month as “Gay Berlin,” last fall, were “Artists Under Hitler,” “Hitler’s Europe Ablaze,” “Atatürk in the Nazi Imagination,” “The Jew Who Defeated Hitler,” “Islam and Nazi Germany’s War,” “Nazi Germany and the Arab World,” and—an Amazon Kindle special—“The Adolf Hitler Cookbook.”

At the same time, Beachy enlarges our understanding of how the international gay-rights movement eventually prospered, despite the catastrophic setbacks that it experienced not only in Nazi Germany but also in mid-century America. Significantly, it was a German immigrant, Henry Gerber, who first brought the fight for gay rights to America, in the nineteen-twenties; Gerber’s short-lived Society for Human Rights, in Chicago, took inspiration from Hirschfeld and perhaps lifted its name from Radszuweit’s group. The Human Rights Campaign, a powerhouse of contemporary gay politics, which was first formed as a political action committee, in 1980, also echoes the German nomenclature, intentionally or not. Furthermore, Radszuweit’s determination to project a well-behaved, middle-class image anticipated the strategy that has allowed the H.R.C. and other organizations to achieve startling victories in recent years. German homosexuals—especially well-to-do men—began to win acceptance when they demanded equal treatment and otherwise conformed to prevailing mores. In this respect, Germany in the period from 1867 to 1933 bears a striking, perhaps unsettling, resemblance to twenty-first-century America.

I closed “Gay Berlin” with a deepened fondness for Hirschfeld, that prolix and imprecise thinker who liked to pose in a white lab coat and acquired the nickname Aunt Magnesia. The good doctor had a vision that went far beyond the victory of gay rights, narrowly defined; he preached the gorgeousness of difference, of deviations from the norm. From the beginning, he insisted on the idiosyncrasy of sexual identity, resisting any attempt to press men and women into fixed categories. To Hirschfeld, gender was an unstable, fluctuating entity; the male and the female were “abstractions, invented extremes.” He once calculated that there were 43,046,721 possible combinations of sexual characteristics, then indicated that the number was probably too small. He remains ahead of his time. ♦

This article appears in the print edition of the January 26, 2015, issue.

References

- The Berlin Story, The New Yorker, 26 January 2015, by Alex Ross https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/01/26/berlin-story