McCarthy and the Mattachine Society

One of the earliest American gay movement organizations, the Mattachine Society began in Los Angeles in 1950-51. It received its name from the pioneer activist Hany Hay in commemoration of the French medieval and Renaissance Societe Mattachine, a somewhat shadowy musical masque group of which he had learned while preparing a course on the history of popular music for a workers’ education project. The name was meant to symbol- ize the fact that “gays were a masked people, unknown and anonymous,” and the word itself, also spelled matachin or matachine, has been derived from the Arabic of Moorish Spain, in which mutawajjihin, is the masculine plural of the active participle of tawajjaha, “to mask oneself.” Another, less probable, derivation is from Italian matto, “crazy.” What historical reality lay behind Hays’ choice of name remains uncertain, just as the members of the group never quite agreed on how the opaque name Mattachine should be pronounced. Such gnomic self- designations were typical of the homophile phase of the movement in which open proclamation of the purposes of the group through a revealing name was regarded as imprudent.

Political Setting.

The political situation that gave rise to the Mattachine Society was the era of McCarthyism, which began with a speech by Senator Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin at a Lincoln’s Birthday dinner of a Republican League in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 9, 1950. In it McCarthy accused the Truman Administration of harboring “loyalty and security risks” in government service. And the security risks, he told Congressional investigators, were in no small part “sex perverts.” A subcommittee of the Senate was duly formed to investigate his charges, which amounted to little more than a list of government employees who had run afoul of the Washington vice squad, but such was the mentality of the time that all seven members of the subcommittee endorsed McCarthyls accusations and called for more stringent measures to “ferret out” homosexuals in government.

The May 1959 issue of the Mattachine Review, an American LGBT magazine

Formation and Structure.

The organization founded by Hay and his associates was in fact modeled in part on the Communist Party, in which secrecy, hierarchical structures, and “democratic centralism “were the order of the day”. Following also the example of freemasonry, the founders created a pyramid of five “orders” of membership, with increasing levels of responsibility as one ascended the structure, and with each order having one or two representatives from a higher order of the organization. As the membership of the Mattachine Society grew, the orders were expected to subdivide into separate cells so that each layer of the pyramid could expand horizontally. Thus members of the same order but different cells would remain unknown to one another. A single fifth order consisting of the founders would provide the centralized leadership whose decisions would radiate downward through the lower orders.

The discussions that led to the formation of the Mattachine Society began in the fall of 1950, and in July 1951 it adopted its official designation. As Marxists the founders of the group believed that the injustice and oppression which they suffered stemmed from relationships deeply embedded in the structure of American society. These relationships they sought to analyze in terms of the status of homosexuals as an oppressed cultural minority that accepted a “mechanically …superimposed heterosexual ethic” on their own situation. The result was an existence fraught with “self-deceit, hypocrisy, and charlatanism” and a “dis- turbed, inadequate, and undesirable . . .sense of value.” Homosexuals collectively were thus a “social minority” unaware of its own status, a minority that needed to develop a group consciousness that would give it pride in it’s own identity. By promoting such a positive self-image the founders hoped to forge a unified national movement of homosexuals ready and able to fight against oppression. Given the position of the Mattachine Society in an America where the organized left was shrinking by the day, the leaders had to frame their ideas in language accessible to non-Marxists. In April 1951 they produced a one-page document settingout their goals and some of their thinking about homosexuals as a minority. By the summer of 1951 the initial crisis of the organization was surmounted as its semipublic meet- ings suddenly became popular and the number of groups proliferated. Hay himself had to sever his ties with the Communist Party so as not to burden it with the onus of his leadership of a group of homosexuals, though by that time the interest of the Communist movement in sexual reform had practically vanished.

Early Struggles and Accomplish- ments.

In February 1952 the Mattachine Society confronted its first issue: police harassment in the Los Angeles area. One of the group’s original members, Dale Jennings, was entrapped by a plain clothesman, and after being released on bail, he called his associates who hastily sum- moned a Mattachine meeting of the fifth order. As the Society was still secret, the fifth order created a front group called Citizens Committee to Outlaw Entrapment to publicize the case. Ignored by the media, they responded by distributing leaflets in areas with a high density of homosexual residents. When the trial began on June 23, Jennings forthrightly admitted that he was a homosexual but denied the charges against him. The jury, after thirty- six hours of deliberation, came out deadlocked. The district attorney’s office decided to drop the charges. The contrast with the usual timidity and hypocrisy in such cases was such that the Citizens Committee justifiably called the outcome a “great victory.”

With this victory Mattachine began to spread, and a network of groups soon extended throughout Southern California, and by May 1953 the fifth order estimated total participation in the society at more than 2,000. Groups formed in Berkeley, Oakland, and San Francisco, and the membership became more diverse as individual groups appealed t o different segments of gay society.

Emboldened by the positive response to the Citizens Committee, Hay and his associates decided to incorporate in California as a not-for-profit educational organization. The Mattachine Foundation would be an acceptable front for interacting with the larger society, especially with professionals and public officials. It could conduct research on homosexuality whose results could be incorporated in an educational campaign for homosexual rights. And the very existence of the Foundation would convince prospective members that there was nothing illegal about participation in an organization of this kind. The fifth order had modest success in obtaining professional support for the Foundation. Evelyn Hooker, a research psychologist from UCLA, declined to join the board of directors, but by keeping in close touch with Mattachine she obtained a large pool of gay men for her pioneering study on homosexual personality.

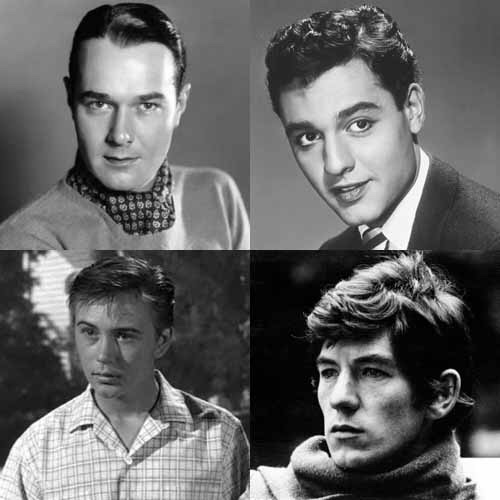

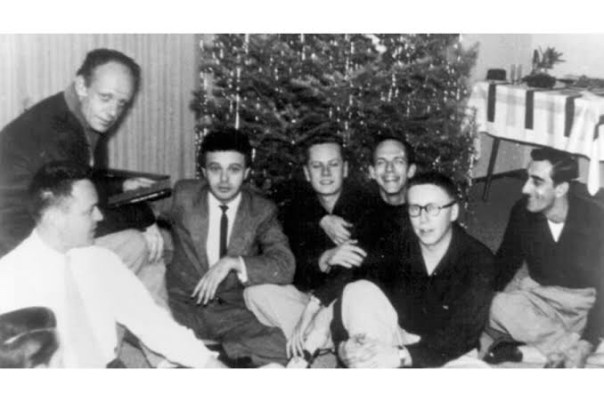

Dick Leitsch, president of Mattachine Society of New York, at its offices, December 30, 1965. Photo by Louis Liotta/New York Post. Source: NYP Holdings, Inc. via Getty Images.

Crisis.

The political background of Hay and the other founders, while it gave them the skills needed to build a movement in the midst of an intensely hostile society, also compromised them in the eyes of other Americans. An attack on the Mattachine Society by a Los Angeles newspaper writer named Paul Coates in March 1953 linked “sexual deviates” with “security risks” who were banding together to wield “tremendous political power.” To quiet the furor, the fifth order called a two-day convention in Los Angeles in April 1953 in order to restructure the Mattachine Society as an above-ground organizaion. The founders pleaded with the Mat- tachine members to defend everyone’s First Amendment rights, regardless of political affiliations, since they might easily find themselves under questioning by the dreaded House Un-American Activities Committee. Kenneth Burns, Marilyn Rieger, and Hal Call formed an alliance against the leftist leadership that was successful at a second session held in May to complete work on the society’s constitution. The results of the meeting were paradoxical in that the views of the founders prevailed on every issue, yet the anti-Communist mood of the country had so peaked that the fifth-order members agreed among themselves not to seek of- fice in the newly structured organization, and their opponents were elected instead. The convention approved a simple membership organization headed by an elected Coordinating Council with authority to establish working committees. Regional branches, called “area councils,” would elect their own officers and be represented on the main council. The unit for membership participation became the task-oriented chapter. Harry Hay emerged from the fracas crushed and despondent, and never again played a central role in the gay movement.

Mattachine Restructured.

The new leadership changed the ideology of the Mattachine Society. Rejecting the notion of a “homosexual minority,” they took the opposite view that “the sex variant is no different from anyone else except in the object of his sexual expression.” They were equally opposed to the idea of a homosexual culture and a homosexual ethic. Their program was, in effect, assimi- lationist. Instead of militant, collective action, they wanted only collaboration with the professionals – “established and recognized scientists, clinics, research, organizations and institutions – the sources of authority in American society. The discussion groups were allowed to wither and die,while the homosexual cause was to be defended by proxy, since an organization of “upstart gays . . . would have been shattered and ridiculed.” At an organization-wide convention held in Los Angeles in November 1953, the conflict between the two factions erupted in a bitter struggle in which the opponents of the original perspective failed to put through motions aimed at driving out the Communist members, but the radical, militant impulse was gone, and many of the members resigned, leaving skeleton committees that could no longer function. Over the next year and a half, the Mattachine Society continued its decline. At the annual convention in May 1954,only forty- two members were in attendance, and the presence of women fell to token representation.

An important aspect of Mattachine was the issuing of two monthly periodicals. ONE Magazine, the product of a Los Angeles/ discussion group, began in January 1953, eventually achieving a circulation of 5000 copies. Not formally part of Mattachine, in time the magazine gave rise to a completely separate organization, ONE, Inc., which still flourishes, though the periodical ceased regular publication in 1968. In January 1955 the San Francisco branch began a somewhat more scholarly journal, Mattachine Review, which lasted for ten years.

Helped by these periodicals, which reached many previously isolated individuals, Mattachine became better known nationally. Chapters functioned in a number of American cities through the 1960s, when they were also able to derive some strength from the halo effect of the civil rights movement. As service organizations they could counsel individuals who were in legal difficulties, needed psychotherapy, or asked for confidential referral to professionals in appropriate fields. However, they failed to adapt to the militant radicalismof the post-Stonewall years after 1969, and they gradually went under. The organization retains, together with its lesbian counterpart, the Daughters of Bilitis, its historical renown as the legendary symbol of the “homophile” phase of the American gay movement.

BIBLIOGUPHY. John D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making o f a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1 970, Chicago: Chicago University Press,1983.

Reference

- Mattachine Society, Williamapercy.com, by Warren Johansson http://williamapercy.com/wiki/images/Mattachine.pdf