“Adolf Hitler was my God. He was sort of like my Fuhrer, my leader. And everything I done was, like, for Adolf Hitler.”

NICKY CRANE

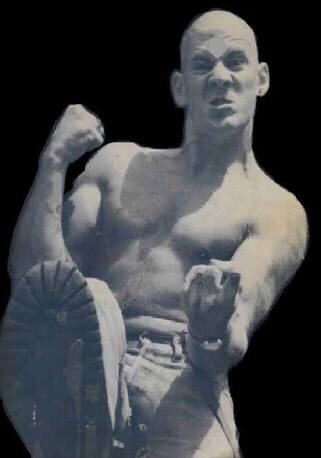

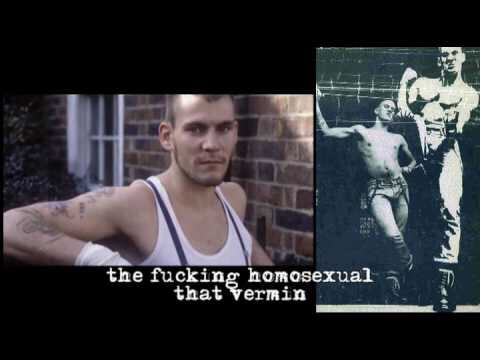

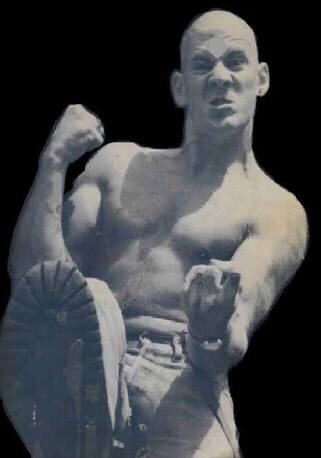

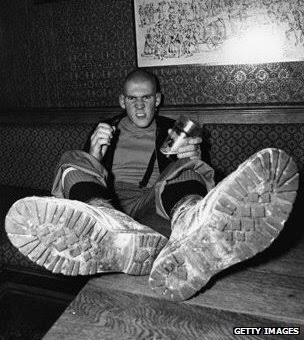

As part of my writing degree from the University of Technology in Sydney (2001) I studied a subject called Contemporary Cultures. Subsequently, I find the study of sub-cultures and “aberrations” within the Gay and Lesbian community a fascinating subject. However, occasionally a subject comes along that I find particularly disconcerting, and gay neo-nazi’s is one that confounds me! How a gay man could attach himself to the insidious writings and philosophies of one of the twentieth centuries greatest tyrants – especially one who condemned thousands of gay men and women to the ovens of the concentration camps – leaves me confused, and wondering…have they really studied what this movement was all about, and if they did, how could they be so dispassionate about it! Perhaps we can be reconciled to them by the fact that even they realised the contradiction, and gave up this somewhat insidious belief. However, the question remains – why? To be honest, and to be contradictory myself, I find the photo below a bit of a turn-on! Not the singlet…that is just wrong…but the man himself – oh yeah! There is an ultra-masculinity about him that is very sexy…and perhaps we should just leave it at that! The photo, and the man himself, are two different things!

Nicola Vincenzo Crane was born on 21 May 1958 in a semi-detached house on a leafy street in Bexley, south-east London. One of 10 siblings, he grew up in nearby Crayford, Kent.

As his name suggests, he had an unlikely background for a British nationalist and Aryan warrior. He was of Italian heritage through his mother Dorothy, whose maiden name was D’Ambrosio. His father worked as a structural draughtsman.

But from an early age Crane found a surrogate family in the south-east London skinhead scene. He was the British extreme right’s most feared streetfighter. But almost right up to his death, Nicky Crane led a precarious dual existence – until it fell dramatically apart.

“ I hate the fact that’s cool to be black these days. I hate this hip-pop fuckin’ influence on white-fuckin’ suburbia.”

“You think I’m gonna sit here and smile while some fuckin’ kike tries to fuck my mother? […] fuckin’ forget it, not on my watch, not while I’m in this family. I will fuckin’ cut your Shylock nose off and stick it up your ass before I let that happen.” Derek Vinyard, American ing movie X

The similarity in thinking between Derek Vinyard in the above aggressive, frightening movie, and Nicky Crane has one major difference – the former is scripted.

The skinhead gang marched in military formation down the High Street clutching iron bars, knives, staves, pickaxe handles and clubs.

There were at least 100 of them. They had spent two days planning their attack. The date was 28 March 1980.

Soon they reached their target – a queue of mostly black filmgoers outside the Odeon cinema in Woolwich, south-east London.

Then the skinheads charged.

Most of them belonged to an extreme far-right group called the British Movement (BM).

This particular “unit” had already acquired a reputation for brutal racist violence thanks to its charismatic young local organiser. Many victims had learned to fear the sight of his 6ft 2in frame, which was adorned with Nazi tattoos. His name was Nicky Crane.

But as he led the ambush, Crane was concealing a secret from his enemies and his fascist comrades alike. Crane knew he was gay, but hadn’t acted on it. Not yet.

A boy stands in front of a poster featuring Nicky Crane

“When you’ve come from a tough background, when you get that identity, it’s a powerful thing to have,” says Gavin Watson, a former skinhead who later got to know Crane.

The south-east London skins also had close connections to the far right. Whereas the original skinheads in the late 1960s had borrowed the fashion of Caribbean immigrants and shared their love of ska and reggae music, a highly visible minority of skins during the movement’s revival in the late 1970s were attaching themselves to groups like the resurgent National Front (NF).

In particular the openly neo-Nazi BM, under the leadership of Michael McLaughlin, was actively targeting young, disaffected working-class men from football terraces as well as the punk and skinhead scenes for recruitment.

Crane was an enthusiastic convert to the ideology of National Socialism.

“Adolf Hitler was my God,” he said in a 1992 television interview. “He was sort of like my Fuhrer, my leader. And everything I done was, like, for Adolf Hitler.”

Within six months of joining the BM, Crane had been made the Kent organiser, responsible for signing up new members and organising attacks on political opponents and minority groups.

He was also inducted into the Leader Guard, which served both as McLaughlin’s personal corps of bodyguards and as the party’s top fighters. Members wore black uniforms adorned with neo-Nazi symbols and were drilled at paramilitary-style armed training weekends in the countryside.

“By appearance and reputation he (Nicky Crane) was the epitome of right-wing idealism – fascist icon and poster boy,” writes Sean Birchall in his book “Beating the Fascists”, a history of AFA.

They were also required to have a Leader Guard tattoo. Each featured the letters L and G on either side of a Celtic cross, the British Movement’s answer to the swastika. Crane dutifully had his inked on to his flesh alongside various racist slogans.

By now working as a binman and living in Plumstead, Crane quickly acquired a reputation, even among the ranks of the far right, for exceptionally brutal violence.

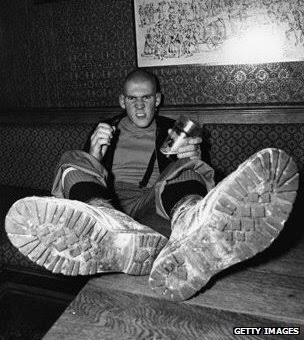

A young Crane shows off his tattoos with another skinhead

A young Crane shows off his tattoos with another skinhead

In May 1978, following a BM meeting, he took part in an assault on a black family at a bus stop in Bishopsgate, east London, using broken bottles and shouting racist slogans. An Old Bailey judge described Crane as “worse than an animal”.

The following year he led a mob of 200 skinheads in an attack on Asians in nearby Brick Lane. Crane later told a newspaper how “we rampaged down the Lane turning over stalls, kicking and punching Pakistanis”.

The Woolwich Odeon attack of 1980 was described by a prosecutor at the Old Bailey as a “serious, organised and premeditated riot”. After their intended victims fled inside, the skinheads drilled by Crane began smashing the cinema’s doors and windows, the court was told. A Pakistani man was knocked unconscious in the melee and the windows of a nearby pub were shattered with a pickaxe handle.

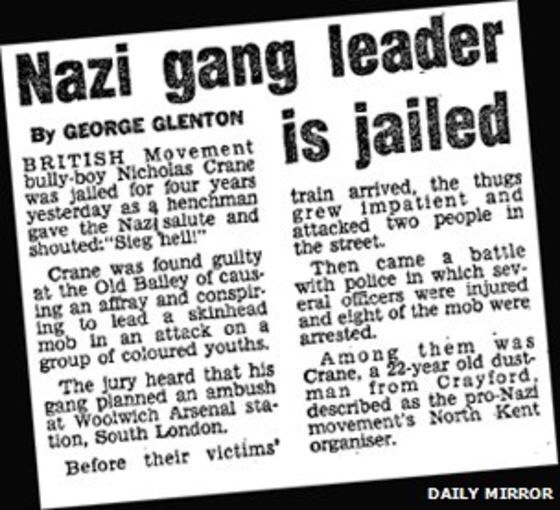

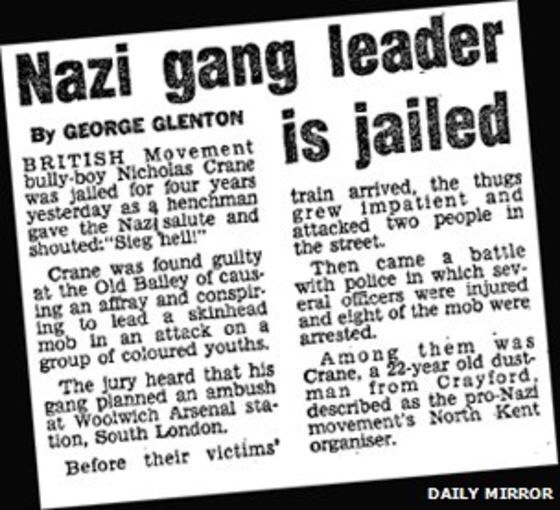

In 1981 Crane was jailed for his part in an ambush on black youths at Woolwich Arsenal station. As the judge handed down a four-year sentence, an acolyte standing alongside Crane stiffened his arm into a Nazi salute and shouted “sieg heil” from the dock.

Crane’s three jail terms failed to temper his violence. During one stretch, he launched an attack on several prison officers with a metal tray. A six-month sentence following a fracas on a London Tube train was served entirely at the top-security Isle of Wight prison – a sign of just how dangerous he was regarded by the authorities.

Nicky Crane’s legendary status escalated even more when he was featured in the cover of the album Strength Thru Oi! (1981), a compilation of crude songs of a popular punk sub-genre among skinheads. He appears grumbling, kicking to the camera’s direction. His violent attitude became an insignia of British Fascist movements. His image was printed on posters and t-shirts that were particularly popular among Neo-nazi followers.

In addition to his prominent membership in the brutal Nazi world, Crane was also a head of security of the band Skrewdriver, whose lyrics and music clearly evidenced their Fascist ideology. Craned developed a bond with Skrewdriver’s vocalist, Ian Stuart Donaldson, and together they founded the skinhead racist organization Blood & Honor.

Skrewdriver was founded in 1976 in Poulton-le-Fylde, a small town in Lancashire, England, by frontman Ian Stuart, who’d previously fronted a Rolling Stones cover band called Tumbling Dice. Skrewdriver began as a punk outfit, but quickly adopted the skinhead uniform: Bic-ed heads, white T-shirts, Levi’s, and “boots and braces” (steel-toe Doc Martens and suspenders). They weren’t overtly political at the outset, but they soon drew a strain of rabid fans sympathetic to radical politics, and drifted ever rightward. In the late 1970s, the group was dropped by their label, Chiswick Records, once their message became overtly violent; clubs throughout Britain refused to let them play.

But, though marginal, there was support for Skrewdriver and their ilk. The National Front, a far-right political party which was experiencing sharp growth throughout the 1970s, saw in Skrewdriver an opportunity for propaganda, and started its own record label, the cleverly named White Noise, on which the band released five early singles. Skrewdriver maintained an allegiance to a range of far-right groups and causes in the UK, including the National Front and the British Movement (BM), a neo-Nazi group founded in the late 60s and known for violence. BM wasn’t just lip service, either. The group had a trained elite, the Leader Guard, who spent weekends doing armed, paramilitary-style drills in the countryside. They regularly attacked members of racial minorities with broken bottles, clubs, or simply their fists.

Nicky began roadie-ing for Skrewdriver in 1983, and his association with the group boosted their reputation for brutality. Crane and Ian Stuart started Blood & Honour, a still-active, neo-Nazi political and social club, together in 1987. Crane, known for his temper and for leading ambushes against unsuspecting minorities (one judge called him “worse than an animal”) was living a double life, however. He was outed as gay after it was reported that he frequented Heaven, a London nightclub.

The outside world continued on without the presence of Crane. Groups against Fascism began to emerge, such as the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) and Anti-Fascist Action (AFA). Without their leader, Neo-Nazis could not counteract the destabilizing attacks of these new clicks. They also weren’t prepared to learn the truth about their hero. The possibility that Crane was homosexual would have never never crossed their minds, even though he secretly frequented London gay bars. Given his savage behavior and hatred towards groups that went against Fascist ideologies, no one was prepared to accept Crane’s sexual orientation.

Unbeknown to his comrades, however, a very different side to Nicky Crane was emerging.

Crane was aware of the contradictions that he embodied and was burdened by his status as one of the most prestigious icons of Fascism. To preserve his reputation, he would make public appearances with skinhead girls who pretended to be his girlfriends. Nonetheless, Crane attended a gay pride rally on 1986 and appeared in gay amateur pornography videos.

The anti-fascist magazine Searchlight was, despite its political leanings, required reading for activists on the extreme right. Each month the publication would run gossip about the neo-Nazi scene, and fascists would furtively buy it to see whether they had earned a mention.

In April 1985 it ran a feature on Crane. It mentioned the GLC concert, the south London attacks and the jail sentences he had served. The magazine revealed it had received a Christmas card from him during his time on the Isle of Wight in which he proclaimed his continued allegiance to “the British Movement tradition” – that is, violence.

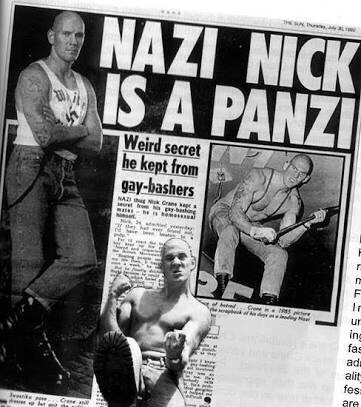

The Searchlight report ended its description of Crane with the line: “On Thursday nights he can be found at the Heaven disco in Charing Cross.”

Even a neo-Nazi audience might have been aware that Heaven was at this point London’s premier gay club. Nicky Crane had been outed. And homosexuality was anathema to neo-Nazis.

But the response of Crane’s comrades to the revelation was to ignore it.

A number of factors allowed Crane to brush off the report, Pearce says. Firstly, homosexuality was indelibly associated with effeminacy by the far right, and Crane was the very opposite of effeminate.

Secondly, no-one wanted to be seen to believe Searchlight above the word of a committed soldier for the Aryan cause.

Thirdly, on the most basic level, everyone was afraid of being beaten up by Crane if they challenged him.

“I remember it was just sort of furtive whispering,” adds Pearce. “I’m not aware that anyone confronted Nicky. People were happy for things to remain under the carpet.”

Sightings at gay clubs were dismissed by Crane.

Donaldson claimed Crane told him that he was obliged to take jobs at places like Heaven because the security firm he was employed by sent him there.

“I accepted him at face value, as he was a nationalist,” Donaldson told a fanzine years later.

For his part, Heaven’s then-owner, Jeremy Norman, says he does not recall Crane working on the door: “I would imagine that the door staff would have been supplied by a security contractor and that he would have been their employee but it is all a long time ago.”

Rumours circulated that a prominent football hooligan and far-right activist had hurled a homophobic slur at Crane, who in response had inflicted a severe beating which the victim was lucky to survive.

Word of this spread among the skinhead fraternity, too.

“My mate had a shop in Soho,” recalls Watson. “People would come in to say, ‘Have you heard Nicky’s gay?’ He would say, he works around the corner, why don’t you go and ask him? Of course they never did.”

Just as some in the gay community refused to believe that a gay man could be a neo-Nazi, others on the extreme right were unable to acknowledge that a neo-Nazi could be a gay man.

Searchlight reported in October 1987 that “Crane, the right’s finest example of a clinical psychopath, is also engaged in building a ‘gay skins’ movement, which meets on Friday nights” at a pub in east London.

Crane’s sexuality might by now have been obvious to any interested onlooker, but the neo-Nazi scene remained in denial.

While his right-wing colleagues studiously ignored the report, AFA took an interest. Its activists put the pub under surveillance.

The anti-fascists didn’t care about Crane’s sexuality, but were concerned that the gatherings might have a political objective. “Here were gay skinheads wearing Nazi regalia,” says Gary. “We could never get to the bottom of it – whether it was purely a sexual fetish.”

The gay community had, by this stage, begun to take notice of Crane, too. He was confronted by anti-fascists attending a Pride rally in Kennington, south London, in 1986.

The campaigner Peter Tatchell recalls a row erupting after it emerged Crane had been allowed to steward a gay rights march. The organisers had not been aware who Crane was or what his political affiliations were.

But now they were, and Crane must have realised he would no longer be welcome in much of gay London. The gay skinhead night may simply have been an attempt to carve out a space for himself where he would not be challenged either for his sexuality or his politics.

While his status in the far right was secure, he was being pushed to the fringes of the gay community. The double life he had been maintaining was beginning to erode.

After the Bloody Sunday march, there is no record of Crane taking part in any further political activity. He had begun drifting away from the extreme right.

Friends say he had begun spending an increasing amount of time in Thailand, where his past was not known and he could, for the first time since Strength Thru Oi! was released, be anonymous.

It was until 1992 that the ruthless Neo-nazi leader publicly accepted his homosexuality in a TV documentary called Skin Complex.

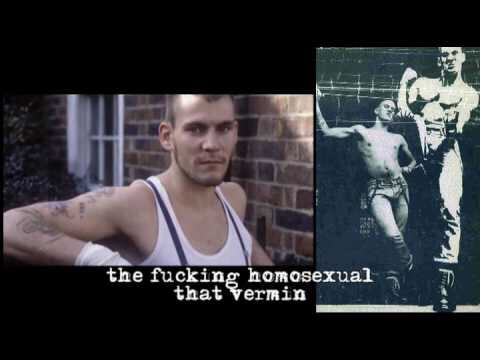

The Channel 4 programme was called Out. It featured a series of documentaries about lesbian and gay life in the UK. The episode broadcast on 27 July 1992 was about the gay skinhead subculture. Its star attraction was Nicky Crane.

First the programme showed recorded interviews with an unwitting Donaldson, who sounded baffled that such a thing as gay skinheads existed, and NF leader Patrick Harrington.

And then the camera cut to Crane, in camouflage gear and Dr Martens boots, in his Soho bedsit.

He told the interviewer how he’d known he was gay back in his early BM days. He described how his worship of Hitler had given way to unease about the far right’s homophobia.

He had started to feel like a hypocrite because the Nazi movement was so anti-gay, he said. “So I just, like, couldn’t stay in it.” Crane said he was “ashamed” of his political past and insisted he had changed.

“The views I’ve got now is, I believe in individualism and I don’t care if anyone’s black, Jewish or anything,” he added. “I either like or dislike a person as an individual, not what their colour is or anything.”

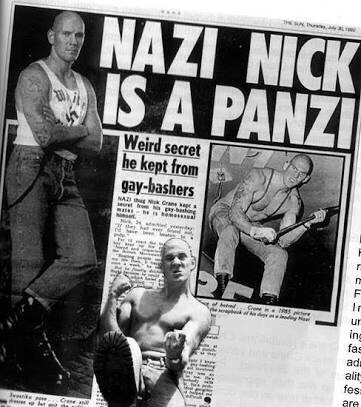

The aim of the program was to explore homosexuality in different subcultures like the skinhead movement. The revelation attracted considerable press attention. The Sun ran a story with the headline “NAZI NICK IS A PANZI”. Below it described the “Weird secret he kept from gay-bashers”.

Crane reiterated that he had abandoned Nazi ideology. “It is all in the past,” he told the paper. “I’ve made a dramatic change in my life.”

The reaction from his erstwhile comrades was one of horror and fury. Donaldson issued a blood-curdling death threat on stage at a Skrewdriver gig.His appearance turned him into the object of scorn of various Fascist groups and also people who once were his friends, like Ian Stuart Donaldson, who declared with frustration:

“He’s dug his own grave as far as I’m concern. I was fooled the same as everybody else. Perhaps more than everybody else. I felt I was betrayed by him and I want nothing to do with him whatsoever.”

But according to Pearce – who by this stage had made his own break with the NF – it was Crane’s disavowal of National Socialism, rather than the admission of his sexuality, that proved particularly painful for Donaldson.

“I think that Ian would have been very shocked,” says Pearce. “He was deeply hurt. But it had more to do with the fact that he switched sides politically.

“Nicky didn’t just come out as a homosexual, he became militantly opposed to what he previously believed in.”

British Nazism had lost its street-fighting poster boy. For the first time in his adult life, however, Crane was able to be himself.

Watson recalls catching a glimpse of Crane – by then working as a bicycle courier – shortly after he came out. “I saw him riding around Soho in Day-Glo Lycra shorts,” remembers Watson. “I thought, good for you.”

Certainly, after coming out, Crane always described himself as gay rather than bisexual.

Nonetheless, his relationships with women, coupled with rumours that he had fathered a son, allayed any initial suspicions his comrades might have had. So too did his propensity for racist violence.

On 8 December 1993, Byrne took the train to London. He had arranged to meet his friend Nicky Crane at Berwick Street market, just a few yards from his Rupert Street bedsit.

Byrne was looking forward to having “a good old chat” about skinheads they both knew. But Crane didn’t turn up.

When Byrne got home, he found out why. Crane had died the day before. He was 35. The cause of death was given on his death certificate as bronchopneumonia, a fatal inflammation of the air passages to the lungs.

He was a victim of the disease that had killed so many other young gay men of his generation.

“He didn’t tell me about his problems with Aids,” says Byrne. “He didn’t talk much about it really. I thought it was a shame.”

Word had got around that Crane was ill, however. Gary recalls his shock at seeing his one-time foe looking deeply emaciated, waiting on a platform at Baker Street Tube station. Crane’s stature was such, however, that even at this point fellow passengers were careful to keep their distance.

Those who suffered as a result of his rampages may have breathed a sigh of relief that he was no longer able to terrorise them.

But his death marked more than just the end of Nicky Crane.

It also coincided with the passing of an era in which the extreme right hoped to win power by controlling the street with boots and fists.

In 1993, Crane was dead, Donaldson died in a car crash and the British National Party (BNP) won its first council seat in Millwall, east London. The various factions of the NF had by now all but withered.

The following year, BNP strategist Tony Lecomber announced there would be “no more meetings, marches, punch-ups” – instead, the intention now was to win seats in town halls. The party would try to rebrand itself as respectable and peaceful – a strategy continued, with varying success, under the leadership of Nick Griffin. Streetfighters like Nicky Crane were supposedly consigned to the past.

The broader skinhead movement was changing, too.

Watson, like many other former skins, had by the time of Crane’s death, abandoned boots and braces for the rave scene. His skinhead days already felt like a different age.

“The skinhead stuff was washed away by rave and it’s, ‘Oh yes, Nicky’s out of the closet,'” Watson says. “It’s the story of that side of skinheads, isn’t it?”

By contrast, the presence of skinheads in gay clubs and bars was no longer controversial. Shorn of its political associations, the look was by now, if anything, more popular in London’s Old Compton Street or Manchester’s Canal Street than on football terraces or far-right rallies.

Two decades after Crane’s death, says Healy, the skinhead is “recognised as a gay man unambiguously in London and Manchester”. He adds: “If the Village People reformed today there would be a skinhead in the group.”

He may be an extreme case, but Crane reflects an era in which people’s expectations of what a gay man looked and behave d like began to shift.

d like began to shift.

“Everybody always knew gay people, but they just didn’t know it,” says Max Schaefer, whose 2010 novel “Children of the Sun” features a character fascinated by Crane. “The neo-Nazis were no different from everyone else.”

It’s unlikely Crane reflected on his place at this intersection between all these late 20th Century subcultures. He was a man of action, not ideology – a doer who left the thinking to others, and this may be what led a confused, angry young man to fascism in the first place.

As he lingered in St Mary’s hospital in Paddington, west London, waiting to die, a young man named Craig was at his side. Craig was “one of Nicky’s closest friends”, says Byrne.

According to Crane’s death certificate, Craig was with him at the end.

References

A young Crane shows off his tattoos with another skinhead

A young Crane shows off his tattoos with another skinhead

d like began to shift.

d like began to shift.