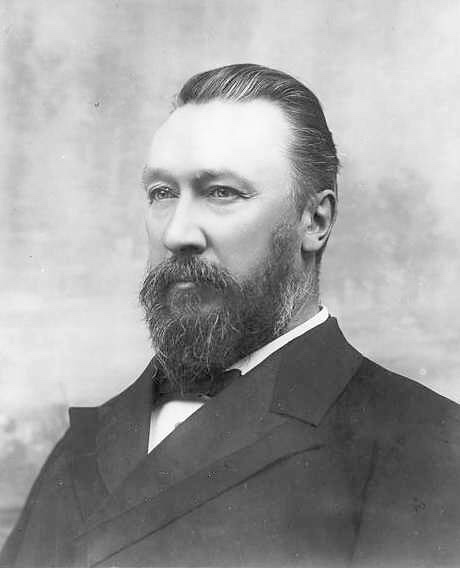

J. Edgar Hoover led a deeply repressed sexual life, living with his mother until he was 40, awkwardly rejecting the attention of women and pouring his emotional, and at times, physical attention on his handsome deputy at the FBI, according to the new movie, “J. Edgar,” directed by Clint Eastwood.

Filmgoers never see the decades-long romance between the former FBI director, and his number two, Clyde Tolson, consummated, but there’s plenty of loving glances, hand-holding and one scene with an aggressive, long, deep kiss.

So was the most powerful man in America, who died in 1972 — three years after the Stonewall riots marked the modern gay civil rights movement — homosexual?

Eastwood admits the relationship between Hoover, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, and Clyde Tolson, played by Armie Hammer, is ambiguous.

“He was a man of mystery,” he told ABC’s “Good Morning America” last week. “He might have been [gay]. I am agnostic about it. I don’t really know and nobody really knew.”

In public, Hoover waged a vendetta against homosexuals and kept “confidential and secret” files on the sex lives of congressmen and presidents. But privately, according to some biographers, he had numerous trysts with men, including a lifelong affair with Tolson.

Dissociation — denying homosexuality, but displaying sexual behavior — is “not uncommon,” according to Dr. Jack Drescher, a New York City psychiatrist who is an expert in gender and sexuality.

Men with strong attractions to other men can have different degrees of acceptance from being fully closeted to being openly gay. And even if they are homosexually self-aware, they can embrace it or reject it publicly.

“We confuse sexual orientation with sexual identity,” said Drescher. “Some men do not publicly identify as gay, regardless of their sexual behavior.”

Even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tracks a group that is not labeled “gay” but “men who have sex with men.“

Roy Cohn, the lawyer who served as chief counsel to Sen. Joseph McCarthy in his anti-communist campaign of the 1950s and who successfully convicted Julius and Ethel Rosenberg of espionage, denied he was gay, despite an attraction to men.

Cohn, who died of AIDS in 1986, was a contemporary of Hoover and according to one biography, the two attended sex parties together in New York in the 1950s.

Cohn was characterized in a scene from Tony Kuschner’s play, “Angels in America,” speaking to his doctor: “…you are hung up on words, on labels, that you believe they mean what they seem to mean. AIDS. Homosexual. Gay. Lesbian. You think these are names that tell you who someone sleeps with, but they don’t tell you that … Roy Cohn is a heterosexual man, Henry, who f****s around with guys.”

Hoover’s degree of self-awareness may have been the same as Cohn’s. Despite his same-sex dalliances, he occasionally sought a “Mrs. Hoover” and even courted — albeit uncomfortably — actress Ginger Rogers’ mother and actress Dorothy Lamour.

Hoover’s neuroses were likely rooted in childhood: He was ashamed of his mentally ill father and was dependent on his morally righteous mother, Annie, well into middle age. Until her death in 1938, Hoover had no social life outside the office.

In the film, Annie chastises her powerful son as he wilted before some of his FBI critics, telling him, “I’d rather have a dead son than a daffodil for a son.”

In a 2004 biography by Richard Hack, “Puppetmaster,” which was culled from the notes of Truman Capote, who had begun interviews on Hoover and Tolson’s relationship, the author says Hoover was not gay, but suggests the man was vicariously turned on by the smut he collected on others.

One 200-page secret document was on the extracurricular activities of Capote himself, who was openly gay.

But Anthony Summers, who exposed the secret sex life of Hoover in his 1993 book, “Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover,” said there was no ambiguity about the FBI director’s sexual proclivities.

“What does Clint Eastwood know about it?” he asked ABCNews.com. Summers collaborated with historians and conducted 800 interviews for the book, including nieces and those who were young enough at the time to have known the man personally.

“We were able to get a close view of the man as an individual and as a human being — as close as anybody who had not been afraid of him since he died,” said Summers.

With interest in the Eastwood film, publishers in the U.S. and in Britain are issuing a remake of the book.

One medical expert told Summers that Hoover was “strongly predominant homosexual orientation” and another categorized him as a “bisexual with failed heterosexuality.”

Hoover often suppressed his urges, but would break out in lapses that could have destroyed him — alleged orgies in New York City hotels and affairs with teenage boys in a limousine, according to interviews conducted by Summers.

“He was a sadly repressed individual, but most people, even J. Edgar Hoover, let go on occasion,” he said.

Hoover as a Cross-Dresser Is Controversial

One short scene in the film showed the FBI director in anguish over his mother’s death, putting on her dress and beads, a nod to Summers expose that Hoover had been a cross-dresser.

The Washington Post recently dismissed that account because of a discredited source, but Summers maintains he had two other independent sources from different periods in Hoover’s life.

Hoover often frequented New York City’s Stork Club and one observer — soap model Luisa Stuart, who was 18 or 19 at the time — told Summers she saw Hoover holding hands with Tolson as they all rode in a limo uptown to the Cotton Club in 1936.

“I didn’t really understand anything about homosexuality at the time,” said Stuart. “But I’d never seen two men holding hands. And I remember asking Art [Arthur] about it in the car on the way home that night. And he just said, ‘Oh, come on. You know,’ or something like that. And he told me they were queers or fairies — the sort of terms they used in those days.”

Hoover promoted men inclined to homosexual indiscretions, including Tolson, who had barely 18 months experience with the FBI when he became Hoover’s deputy.

The pair used to make “saucy jokes” about some of the other agents, like Melvin Purvis, who was a hero for arresting John Dillinger, according to Summers.

Purvis’s son shared his father’s 500-letter correspondence with Hoover, who teased the good-looking, blond-haired agent as “the Clark Gable of the FBI,” even though he was heterosexual.

Many were intimate and one was highly charged with innuendo, as Hoover referred to himself as the “Chairman of the Moral Uplift Squad.”

Ethel Merman, who had known Hoover since 1938, knew his sexual orientation, according to Summers. In 1978 when the actress was asked to comment on Anita Bryant’s anti-gay campaign, Merman told the reporter, “Some of my best friends are homosexual. Everybody knew about J. Edgar Hoover, but he was the best chief the FBI ever had.”

Harry Hay, founder of the Mattachine Society, one of the first gay rights organizations, confirmed that Hoover and Tolson sat in boxes owned by and used exclusively by gay men at their racing haunt Del Mar in California.

“They were nodded together as lovers,” he told Summers.

Another FBI agent who had gone on fishing trips with Hoover and Tolson revealed that the director liked to “sunbathe all day in the nude.” Even novelist William Styron told Summers that he once spotted Hoover and Tolson in a California beach house — the director painting his friends toenails.

But, according to Summers, “Nobody dared say anything, he was so powerful.”

The author interviewed the widow of respected Washington, D.C. psychiatrist Dr. Marshall de G. Ruffin, who treated Hoover in 1946 after his general practitioner had been “puzzled by a strange malaise in his patient.”

Monteen Ruffin told Summers that Hoover was “very paranoid” about anyone finding out, and he eventually stopped seeing the psychiatrist. She said her husband burned the evidence.

“He was definitely troubled by homosexuality,” she said in 1990, “and my husband’s notes would have proved that … I might stir a kettle of worms by making that statement, but everybody then understood that he was a homosexual, not just the doctors.”

As the movie depicts, after Hoover’s death, his loyal secretary Helen Gandy destroys the “official and confidential” files.

When Hoover died in 1972, President Richard Nixon ordered his “dirty tricks man” Gordon Liddy to scour the FBI director’s office for files. But when they arrived, someone had taken “drastic action,” said Summers. Nothing but tables and chairs remained.

Summers said he is often asked, but rarely answers the question about what he personally thought of Hoover as a human being.

“Yes, I had sympathy for somebody who has to bury their real preferences through a long life in the public eye,” he said. “But not sympathy for the way in which he was dictatorial, the way he behaved politically and personally to people right from the beginning in his late teens and early 20s.

“He was totally self-serving and the way in which he was a repressed homosexual didn’t require him to abuse individual rights and human liberties the way he did,” said Summers. “It does not begin to justify his behavior toward blacks and concoct an anonymous letter to Martin Luther King and suggest he end it all and kill himself.”

Psychiatrists have concluded that Hoover “no doubt” had a narcissistic personality disorder, perhaps because of his dependency on a forceful mother who had “great expectations for her son,” he said.

“Studies suggest that people with such backgrounds block their feelings and cut meaningful relationships,” according to Summers, who said Hoover would have been a “perfect high-level Nazi.”

However, Eastwood, who is a Republican, contends that J. Edgar Hoover was “probably good for the country,” and whether he was homosexual or not makes no difference.

“I don’t really know and nobody really knew,” he told ABC. “It’s definitely a love story. You can love a person and whether it goes into the realm of being gay or not, is here nor there.”

A younger generation of gays was moved by the film precisely because it portrayed such an iconic figure’s struggle with his sexuality.

“The audience I was in clearly rooted for Hoover to be gay and to have happiness in his sex and love life,” said Ben Ryan, a 33-year-old novelist from New York City. “In a pivotal scene between DiCaprio and Hammer in which the two men engage in the classic brawl-leads-to-furious-kiss, everyone got so excited when they finally locked lips.”

“Anyone in their right mind would see this movie and say, ‘Oh, well, of course Hoover was gay,'” he said. “The more suspicious among us might think that the filmmakers were still afraid of Hoover’s ghost suing them for libel if they just put it right out there that he was gay.”

Still, he said, the film is a “tragic story that should hopefully teach society lessons about how dangerous sexual repression is.”

Reference

- J. Edgar Hoover: Gay or Just a Man Who Has Sex With Men?, ABC News, 15 November 2011, by Susan Donaldson James https://abcnews.go.com/Health/edgar-hoover-sex-men-homosexual/story?id=14948447