Here’s to the Sunday afternoon Tea Dance phenomenon, a gay tradition which is slowly disappearing.

Many gay men under the age of 30 today are totally clueless of almost lost tradition of the Sunday Tea Dance. (A tradition that really must be brought back.) So here’s a little history primer on the tradition of the “Sunday T-dance” and how and why we embraced it in the LGBT culture.

Historically, tea was served in the afternoon, either with snacks (“low tea”) or with a full meal (“high tea” or “meat tea”). High Tea eventually moved earlier in the day, sometimes replacing the midday “luncheon” and settled around 11 o’clock, becoming the forerunner of what we know as “brunch”.

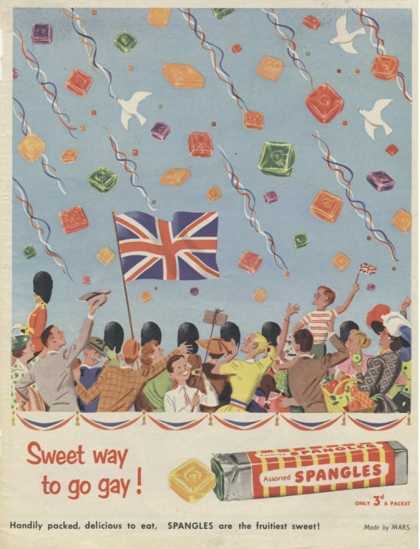

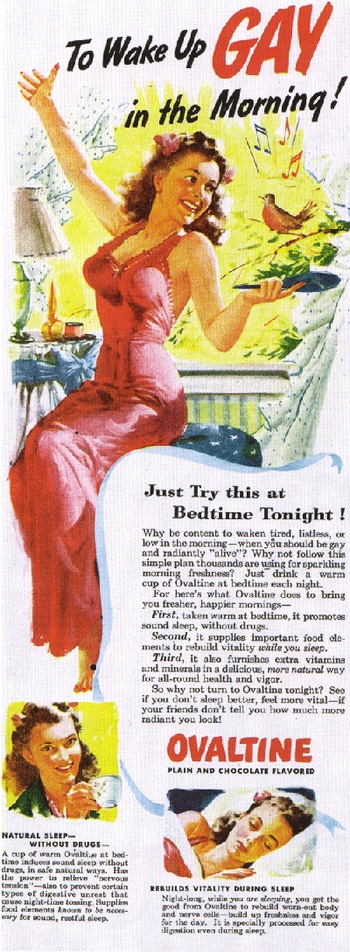

From the late 1800’s to well into the pre-WWI era in both America and England, late afternoon (low) tea service became the highlight of society life. As dance crazes swept both countries, tea dances became increasingly popular as places where single women and their gentlemen friends could meet — the singles scene of the age.

While tea dances enjoyed a revival in America after the Great War, The Great Depression of the 30’s wiped them out. Tea consumption was in steady decline in America anyways and by the 50’s, tea was largely thought of as something “your grandmother drinks”. Also, nightlife was moving later and younger. Working men and women were too busy building the American Dream to socialize so it was left to their teenaged children in the age of sockhops and the jukebox diner. Rock and roll was dark and dangerous — something you sneaked out for after dinner, not took part in before dinner.

Gay people, of course, were still largely underground in the 50s, but it was in these discreet speakeasies that social (nonpartnered) dancing was evolving. It was illegal for men to dance with men, or for women to dance with women. In the event of a raid, gay men and lesbian women would quickly change partners to mixed-couples. Eventually, this led to everyone sort of dancing on their own.

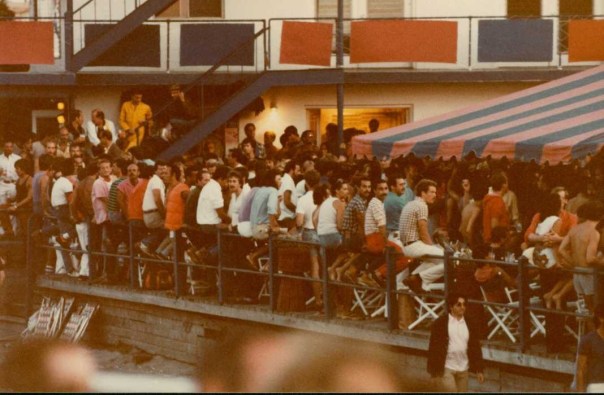

By the late 60s, gay men had established the Fire Island Cherry Grove and also the more subdued and “closeted” Pines (off of Long Island, in New York) as a summer resort of sorts. It was illegal at that time for bars to knowingly sell alcohol to homosexuals and besides many of the venues there were not licensed as ‘night clubs’ or to sell alcohol. To avoid attracting attention, afternoon tea dances were promoted. Holding them in the afternoon also allowed those who needed to catch the last ferry back to the mainland to attend.

The proscription against same-sex dancing was still in effect, so organizers were forced to institute no touching rules. Since there were no lesbians around to change partners with, gay men developed the dancing apart style that club-goers everywhere now take for granted.

June 28, 1969: the Stonewall Riots mark the fiery birth of the so-called “modern gay rights movement”. Following (and in part perhaps inspired by) the death of gay icon Judy Garland, (as the urban legend goes) patrons of the Greenwich Village watering hole The Stonewall Inn fought back against another in a very long line of violent police raids, eventually barricading the police inside the bar and setting off three nights of rioting. The “snapped stiletto heel heard around the world”as some call it is commemorated today with Gay Pride celebrations held around the end of June.

Post-Stonewall, the tea dance moved from the Fire Island Pines to Greenwich Village. A newly-energized gay community around Christopher Street embraced the social dancing craze started on Fire Island. While the Fire Island gays tended to be rich upper-class preppies, the downtown gays of Christopher Street and the Village were working-class and they tended to party at night. As in the straight community, tea dances gradually moved later until they became subsumed into the night club scene.

Through the 70’s, gay men championed the uniform of the working class — t-shirts and denim — as fashion aesthetic. In part because they were affordable, and in part because it projected an appealing hypermasculinity associated with the working class. Gays in the post-Stonewall era were consciously rebelling against the effete stereotypes associated with the manicured, sweater-wearing, tea-drinking gays of the Fire Island set. Real men wore t-shirts and drank beer. Gay men still had afternoon/early evening dances — usually on Sundays, in order to make the most of one’s weekend while still being able to get up for Monday morning’s work.

The downtown gays rejected the term tea dance as being too effete and opted for the supposedly butcher t-dance, and promoted t-shirts and denim as the costume of choice. By the mid 70s, the Christopher Street Clone look (short cropped hair, mustache, plaid shirt over a tight white t-shirt, faded denim jeans that showed off your ass) had made the trans-continental trip from New York City to Los Angeles (gays in Hollywood) and, of course, to San Francisco (follow the Yellow Brick Road and it leads to Castro). It brought with it the tea dance phenomenon, which is slowly dying out and is nothing of its former self and in may places is all but gone.

So grab those fans and poppers boys and and let’s “Ohhhhha, Ooooha” like it’s 1978 again!

Let’s not let Sunday Tea become a piece of our forgotten gay history also.

Reference

- The Very Gay and Interesting History Of The Almost Lost Tradition Of The Sunday Tea Dance, OutWire757, 21 April 2017, by Eric Hause https://outwire757.com/gay-interesting-history-almost-lost-tradition-sunday-tea-dance/