Thunderbolt and Bell

What are these ritual objects?

The vajra (Tibetan: Dorjie) and bell (Sanskrit: ghanta; Tibetan: drilbu) are the most important ritual objects of Tibetan Buddhism. Most every lama has a pair and knows how to use them. They represent “method” (vajra) and “wisdom” (bell). Combined together they symbolize enlightenment as they embody the union of all dualities: bliss and emptiness, compassion and wisdom, appearance and reality, conventional truth and ultimate truth, and male and female, etc.

What is meant by method and wisdom?

Method indicates the compassionate activities of the bodhisattva that relieve living beings of their miseries. It is the skillful means that brings about the elimination of ignorance, greed, cruelty, etc. in living beings and causes them to follow the path to enlightenment. Wisdom is the direct insight into ultimate reality; it is the wisdom that realizes emptiness. By combining method and wisdom, the bodhisattva accumulates merit and insight and eventually attains Buddhahood.

What is the symbolism of the Vajra and bell?

Most vajras have five prongs that symbolize the five wisdoms that are attained through the transcendance of five kleshas (greed, anger, delusion, pride and envy). The hub between them signifies emptiness. This one has eight prongs plus the central hub. Vajra is a Sanskrit word, in Tibetan it is called a dorje. It is related to the word for diamond, and appears to be similar to the thunderbolt weapon carried by the Vedic god Indra, and the Olympian Zeus. As a thunderbolt weapon it destroys both internal and external enemies. As a diamond it symbolizes the indestructible and all-penetrating mind of enlightenment.

The sound of the bell calls to mind the empty nature of all things. That is, according to the Buddha, nothing whatsoever can exist independently, all phenomena are empty of true or inherent existence. By being profoundly aware of the empty nature of all things, we become free of attachment and aversion, and are liberated from the painful cycle of birth and death (samsara). The bell is also a musical instrument Its sound, together with other sacred instruments such as the hand-drum (damaru), are played in rituals as musical offerings to the Buddhas and other gods.

How are they used?

The vajra and bell are often seen represented in the hands of deities in art, and in practice are held in the hands of the monks during rituals, the vajra in the right hand, the bell in the left. They are moved in prescribed movements. When the arms are crossed this symbolizes that the two are united—representing enlightenment. The sound of the bell is considered by Tibetan Buddhists as the most beautiful music. This music is presented as one of eight offerings to the deity that is invoked during the ritual.

What are the eight offerings presented in rituals?

When Tibetans Buddhist begin meditation, they will invoke the presence of the deity, bow, and make offerings. For peaceful deities, the offerings are as follows:

- pure water for the deity to drink

- water for the deity to wash with

- scented oil for the deity to be anointed with

- flowers

- incense

- butter lamps

- food

- music, played on the ghanta (bell) and the damaru, a small two-faced drum with clappers attached by string, played by twisting back and forth in the hand

This thunderbolt and bell were cast for the Chinese Emperor Yongle (1403–1424) as a gift for a distinguished lama of Tibet. The Emperor possibly wished to gain merit for the commission. This and other gifts like it show the relationship between the Tibetan lamas and the emperors of China. Known as the priest-patron relationship, this was one way that ideas and artistic styles spread between China and Tibet. Artists working in China in imperial workshops were ordered to make Tibetan style objects for either the personal use of the emperor or to send to important lamas in Tibet, who were often considered to be their spiritual teachers.

Tibetan Drum (Damaru)

The Tibetan drum, or Damaru, might seem a little familiar. That’s probably because of the way in which you play this instrument. You take the drum and roll it from side to side, whilst small beads on the end of strings will ‘bang’ the leather drum heads. Estimates guess that this instrument reached the Himalayas in around the 8th century, and this wood and leather object has been a staple in the Buddhist faith ever since. Within Buddhism, these Tibetan ritual items hold immense significance during tantric practices.

There are actually three different types of Damaru, each one holding its own properties and purpose. The most widely used is the Chöd Damaru. This tends to be made from wood and covered with leather skins for the drum surface. Usually, they are 8 to 12 inches in diameter, although in rare cases this has been known to vary. The purpose of the Chöd Damaru is to be used during the tantric practice of Chöd, where a believer tries to ‘cut through’ the problems that face them and hinder their quest for enlightenment.

A slightly more grotesque Damaru is that of the Skull Damaru. This is certainly one of the more unusual Tibetan ritual items, and takes the form of a human skull, shaped into that of a drum. This version tends to be used in temples and large festivals, so keep an eye out when visiting Tibetan religious festivals. It’s a unique sight and usually coated in rare and precious stones

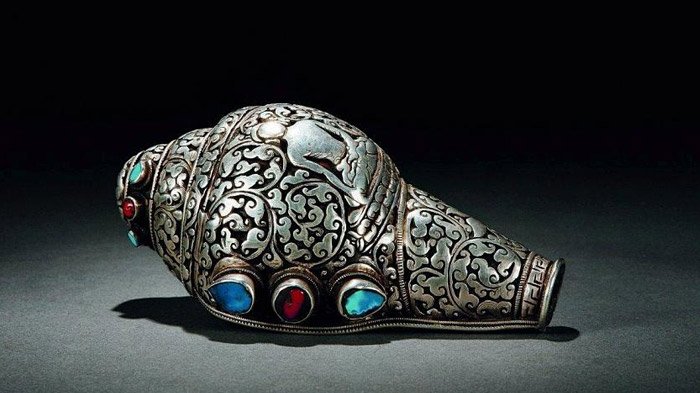

Tibetan Buddhist right-turning conch shell (Shankha)

The Shankha looks like an ornate snail shell. The outside is usually decorated with patterns regarding the Buddhist faith, and is usually painted in light, white colors. The shell is one of the eight auspicious symbols of Buddhism (the Ashtamangala), and represents water and Buddhism’s pervasiveness.

If you want to see one of the conches in person, it tends to be used to bring together and call on followers to meet. During rituals, it is sometimes used as a musical instrument, but can also be used to carry holy water from one place to another.

Tibetan prayer beads (malas)

The Malas is probably one of the most well know Tibetan ritual items. These Tibetan prayer beads are composed of 108 beads, each of which signifies the mortal sins of humanity. The beads themselves tend to be made from the wood of a special tree, known as the Ficus religiosa. Sometimes, bodhi seeds are also used, or rattan seeds. The different materials generally signify different uses, with the wooden beads being seen as generally ‘all-purpose’.

A visit to any Buddhist temple will usually allow you to see the Tibetan prayer beads both on sale, and being used by the monks themselves. Monks will usually count the beads whilst praying.

Gawu box

The Gawu box is an amulet usually made from silver, which is used to hold an image of the Buddha made from metal or clay. The outside is usually decorated with expensive and rare stone, with ornate designs and patterns you’ll find on other Tibetan ritual items as well. Usually, the Gawu is used during prayer to ward off evil spirits and bring about the Buddha’s blessing.

Whilst travelling to Tibetan temples, keep an eye out for the differences you’ll see. One of the most striking is that males tend to wear a square shaped amulet, whilst women will adorn a more rounded one.

Tibetan prayer wheel

The Tibetan prayer wheel is a cylindrical wheel which comes in many different shapes, sizes, and materials. Whilst small, personal ones can be found, there are also those which are much larger and must be held up by (usually) wooden structures. One thing they tend to have in common, though, is that they usually come in gold. The Prayer wheels also tend to be decorated with the 8 auspicious symbols of Ashtamangala.

Larger, stationary prayer wheels tend to be located in most monasteries. Visitors can usually move the wheels themselves by running their hands over them as they walk past.

Tibetan butter lamp

The Tibetan Butter Lamp is found in almost all Tibetan temples and sanctuaries. The (usually) golden cup tends to burn Yak Butter, which represents the illumination of Wisdom. If you head to the temples early in the morning, you’ll find monks taking part in their morning ritual, which consists of an offering of the Tibetan butter lamp, along with seven other bowls containing other symbolic offerings. Pilgrims, whilst travelling between temples, tend to supply oil for these lamps to gain favor.

Reference

- Thunderbolt and bell, Khan Academy, by …No author given…no date given, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/himalayas/tibet/a/thunderbolt-and-bell\

- Top & Holy Ritual Items of Tibetan Buddhism, Tibet Teavel, by KHAM sang, November 26 2019 https://www.tibettravel.org/tibetan-buddhism/ritual-items-of-tibet-buddhism.html

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/MonasteryinTibet-5b5b9dacc9e77c004fc68ce5.jpg)