I was an 80s Clone…many would have said an arch-Clone! I lived the life, and the look. Levi’s jeans, “Bonds” tee-shirts and singlets, plaid flannelette shirts, “Blundstone” boots (Blunnies), or Doc Martins, huge handlebar moustache, a transient beard in any of a number of styles, short or buzz-cut hair, an “Akubra” cowboy hat. I lived in pubs like The Oxford, and danced…half naked…in nightclubs like “Mandate” (Melbourne), and “Midnight Shift” or “Stronghold” in Sydney. I sniffed Amyl, blew whistles, banged tambourines, ingested LSD & Speed when the mood took me, sprinkled talc on dancefloors, and danced in a jockstrap on occasion. Leather vests, belts, armbands and cockrings. Pierced ears, pierced nipples, tattoos. I loved it…though many other gay men, especially older “dinner party” gays, hated it and thought we leaned too heavily on straight stereotypes for our look. What they couldn’t see was that this extreme stereotyping WAS gay! That at THAT time, THEY were the stereotype…along with the effeminate, lisping, limp-wristed stereotype that was the general impression of gay men…was what we were trying to move away from, by presenting a more “macho” type of gay men…that we wanted to be seen as men, not as a parody of! The Clone look, along with Hi NRG dance music became looks and sounds that very much defined the 80s.

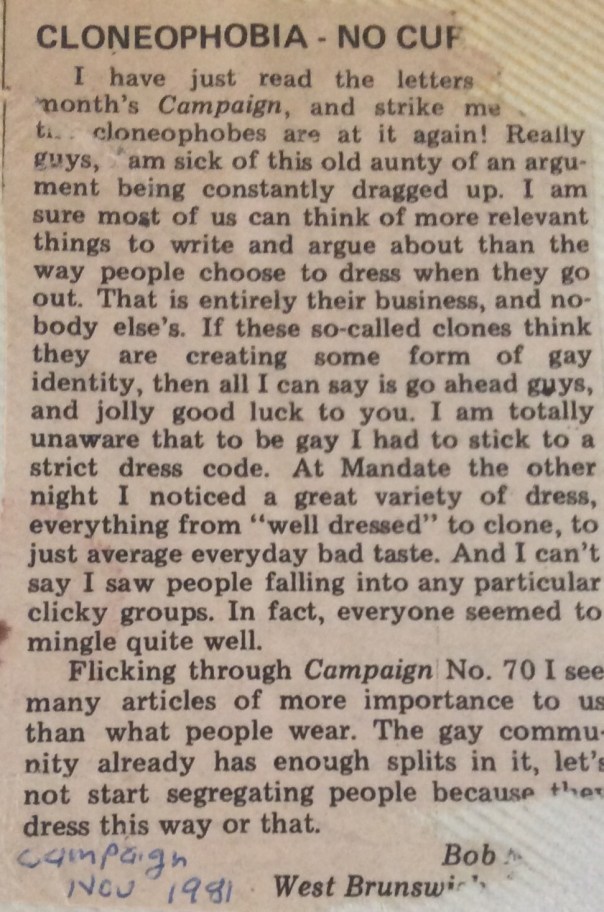

Don’t ask me why it started, but by the beginning of the 80’s ‘the clone’ was beginning to become a universal phenomenon (and I don’t mean Dolly the sheep!).

Some commentators suggest the first clones appeared in San Francisco’s Castro Street; others that they came from New York’s ‘Village’. Either way, by the 80’s the look had been adopted by gay men around the world.

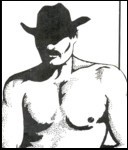

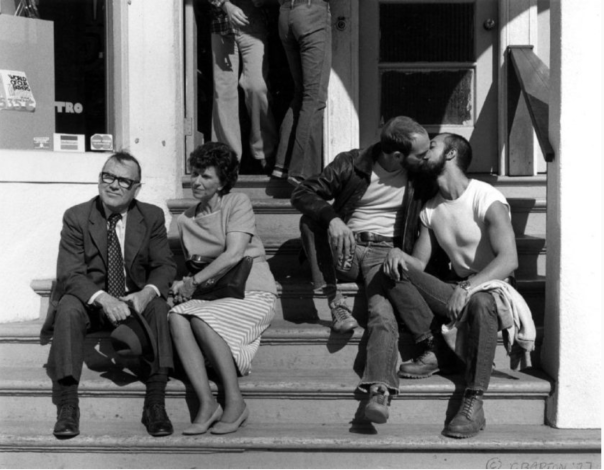

The most obvious elements were the (obligatory) moustache and ‘the uniform’. Depending on where you lived, the latter would be based on a Lacoste sports shirt, chinos and ‘loafers’ (USA) or checked shirt, jeans and trainers (UK). These minor national differences notwithstanding, the overall look was an overt and unambiguous statement – not just about dress sense but also masculinity and sexuality.

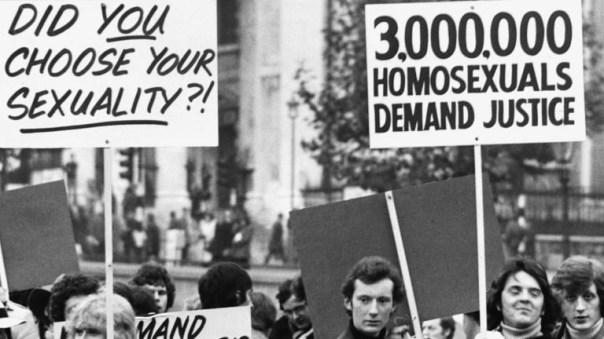

This was an extremely significant act for that time – not least because gay men were, on the whole, still largely closetted. Yet, in spite of this, here were large groups of gay men choosing an image – and a highly sexualised one at that – for themselves. Prior to this, the only ‘sexualised’ images of gay men were as predators – of ‘defenceless’ straight men and, of course, children since we were all paedophiles. And, needless to say, they weren’t images of our choosing.

Within the UK this was also another indication of the Americanisation of gay men or, perhaps more accurately, the gay identity. In a sense, it was almost inevitable, given the sustained hostility to all things gay in the UK (e.g. Mary Whitehouse’s attacks on Gay News, the raiding of Gay’s the Word and other bookshops). The USA was the principal source of many gay resources – from porn to political material. (I shall cover this in more detail in a later blog.)

It could be argued that it was the clones who started to put the sex into homosexual: there are certainly some commentators who believe that they paved the way for other groups such as leather men and bears. Certainly, the collective visibility of so many self-defined gay clones can only have helped put us on the map as a population that was much larger – and a lot less apologetic – than many people had imagined.

Of course, there were always some queens who took it all a bit too seriously. Thankfully, there were others who managed to combine the playful and political elements of the clone. No one in the UK did this more successfully than the artist David Shenton, through his character ‘Stanley’, who appeared regularly in Gay News and then Capital Gay.

I’m not sure if the clone has totally disappeared from the gay scene or simply merged into one of the other diverse ‘identities’ our community now has. But it would be a shame if we were to forget what was our first, ‘home-grown’ positive gay stereotype.

Remaking the Castro Clone

Levis 501 jeans. Skin tight. Sanded down at the knees and crotch for that perfectly worn-in look. Third button unbuttoned to create a bit of allure. T-shirt, also skin tight. A Levis snap-front plaid. That was the uniform of the Castro clone, the gay fashion icon spawned in the 70s that — with surprisingly minor evolution or alteration — can still be seen on the streets of San Francisco today.

Danny Glicker, thankfully, is in love with the look. As the costume designer on Milk, Gus Van Sants biopic of the slain civil rights leader Harvey Milk, Glicker had to outfit hundreds of actors, from leading men Sean Penn, James Franco and Emile Hirsch to an army of extras, all dressed to span a full decades worth of fashion dos and donts.

Period films always present challenges to their costumers, but those based on true stories are that much more complicated. Glicker was saddled with another great expectation while preparing the highly anticipated film: Milks characters are not only real, they lived during a time many viewers can still recall themselves. And Milk owned a camera shop and lived an incredibly well documented life, which took some of the guesswork out of the equation, but also meant that there would be no excuse with eagle-eyed fans for anything less than absolute authenticity.

Simply recreating the clothes wouldnt have been sufficient — the bodies on todays actors are more defined and muscled than those of the leaner Milk and his comrades. Instead Glicker had to tailor the clothes to look as if they were hanging off of a 70s frame.

We created these enormous books of research that specifically address each character within the timeline, says Glicker, a young, unassuming, bespectacled man with a head of thick black curls whose previous work include Transamerica, Thank You For Smoking and HBOs True Blood. It was sort of overwhelming, because after awhile it was hard to edit down the material. I was very interested in recreating outfits exactly as they were, partially because I knew that Gus was going to be incorporating so much archival footage into the movie, and I didnt know exactly where.

Given access to the archives of the San Francisco GLBT Historical Society, Glicker and his team managed to get their hands on a fair amount of Milks actual clothing. Then they went shopping. Glicker, who prefers vintage pieces, combed hundreds of stores and amassed a huge collection of items, which he then authenticated using his research books before altering to fit the actors. No tiny detail of the evolution of fashion went unchecked — there are, after all, key differences between a 1976 shirt and a 1978 shirt (such as the collar width), and Glicker was determined to be accurate.

What couldnt be bought was recreated (and sometimes what was bought was still recreated so that spare sets were available), including T-shirts from now-defunct Castro bars, protest Ts found in the archive, and the suit Milk was killed in, which they had viewed at the Historical Society. That was a very, very meticulous recreation, says Glicker, who had to wear cotton gloves while handling the suit, which is kept in a temperature and light controlled environment and wrapped in acid free tissue. We were measuring everything from the lapels to the belt loops and leg openings. The fabric, every aspect of the fit, it was all done to match as closely as possible.

And when the thrift stores and archives didnt have what he needed, Glicker went to Levis corporate headquarters in San Francisco. The uniform of choice for Harvey Milk, his friends and many in the LBGT community at the time was the Levis 501 button fly jean, says Robert Hanson, President of Levi Strauss & Co.s Levis Brand Division. If you saw anything but Levis in the film it would have been wrong.

Levis gave me a tremendous amount of access to both their archive and retail store, says Glicker. Hanson (who is gay) and Levis, an early pioneer and longtime stalwart supporter for gay causes, thought the film was a perfect match for the brand. The movie is really about a very specific movement at a specific time in the city, Glicker says. These people wore Levis. It was what they were about and where they were. Its more than just a brand of clothes in this case, its an iconic part of America and the Castro.

When I started reading about what people wore, adds screenwriter Dustin Lance Black. I thought, What was that Levis clone look about? It didn’t take much to realize that it was about a group of people who had been called pansies and fags reclaiming their masculinity and being men.

That held true even when going butch went beyond the basics. I remember reading someone complaining that the guys were actually going too far with it — trying to be too butch, actor James Franco, who plays Milks longtime lover, Scott Smith, told Black in his Out cover interview. I saw a lot of guys from the Castro where they [actually] looked like construction workers.

Thats why the Castro clone, Glicker says, is actually a deceptively simple look. It has to be perfectly played, he says. In order to make it look good, you have to find the perfect fit and you have to feel great in it to be able to sell the outfit. It was a uniform because it was accessible for everybody. It wasnt out of peoples grasp. It was about the wearer more than the means of the wearer. And whether or not Milk launches a vintage resurgence, the basic elements havent been put out to pasture. I see the influence of it everywhere. Its not going anywhere. Its like the gay communitys little black dress.

Reference

- Send in the Clones, Gay in the 80s, 26 March 2012, by Colin Clews http://www.gayinthe80s.com/2012/03/clone-ly-planet/

- Remaking the Castro clone, Out.com, 1 December 2008, by Eddie Shaprio https://www.out.com/entertainment/2008/12/01/remaking-castro-clone