The History of Welsh Surnames

Have you ever wondered why there are so many Jones’ in a Welsh phonebook? In comparison to the plethora of surnames which appear in the History of England, the genealogy of Wales can prove extremely complex when trying to untangle completely unrelated individuals from a very small pool of names.

The limited range of Welsh surnames is due in large part to the ancient Welsh patronymic naming system, whereby a child took on the father’s given name as a surname. The family connection was illustrated by the prefix of ‘ap’ or ‘ab’ (a shortened version of the Welsh word for son, ‘mab’) or in the woman’s case ‘ferch’ (the Welsh for ‘daughter of’). Proving an added complication for historians this also meant that a family’s name would differ throughout the generations, although it wasn’t uncommon for an individual’s name to refer back to several generations of their family, with names such as Llewellyn ap Thomas ab Dafydd ap Evan ap Owen ap John being common place.

In the 1300s nearly 50 per cent of Welsh names were based on the patronymic naming system, in some areas 70 per cent of the population were named in accordance with this practice, although in North Wales it was also typical for place names to be incorporated, and in mid Wales nicknames were used as surnames.

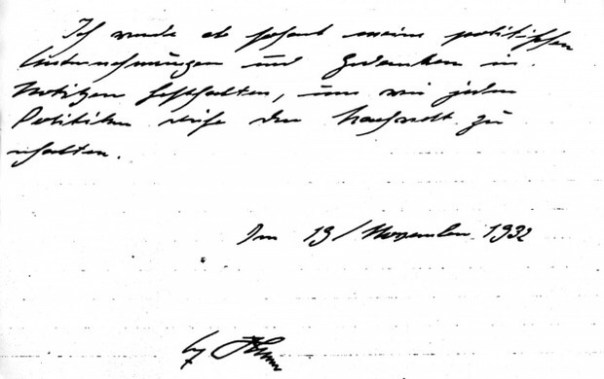

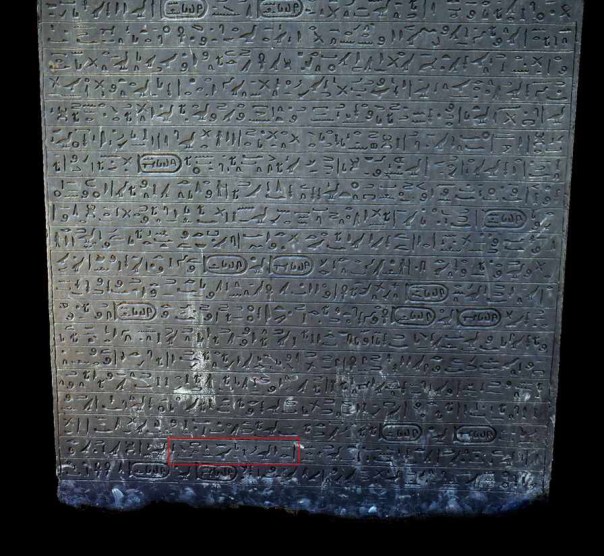

It is thought that the patronymic naming system was introduced as a direct result of Welsh Law, which is alleged to have been formally introduced to the country by Hywel Dda (“Hywel the Good”), King of Wales from Prestatyn to Pembroke between 915AD and 950AD and often referred to as Cyfraith Hywel (the Law of Hywel). The law dictated that it was crucial for a person’s genealogical history to be widely known and recorded.

However, in the wake of the Protestant Reformation in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries this was all set to change. Whilst the English Reformation resulted in part because of the religious and political movement affecting the Christian faith across most of Europe, it was largely based on government policy, namely Henry VIII’s desire for an annulment of his marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Catherine had been unable to bear Henry a son and heir, so he feared a reprisal of the dynastic conflict suffered by England during the War of the Roses (1455-1485) in which his father, Henry VII eventually took the throne on 22 August 1485 as the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Pope Clement VII’s refusal to annul Henry and Catherine’s marriage and leave Henry free to marry again, led to a series of events in the sixteenth century which culminated in the Church of England breaking away from the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. As a result Henry VII became Supreme Governor of the English Church and the Church of England became the established church of the nation, meaning doctrinal and legal disputes now rested with the monarch.

Although the last Welsh Prince of Wales, Llewellyn ap Gruffydd, had been killed during Edward I’s war of conquest in 1282, and Wales had faced English rule with the introduction of English-style counties and a Welsh gentry made up of Englishmen and native Welsh lords who were given English titles in exchange for loyalty to the English throne, Welsh Law still remained in force for many legal matters up until the reign of Henry VIII.

Henry VIII, whose family the Tudors were of welsh decent from the Welsh house of Tudur, had not previously seen a need to reform the Welsh Government during his time on the throne, but in 1535 and 1542, as a result of a supposed threat from the independent Welsh Marcher lords, Henry introduced the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542.

These laws meant that the Welsh legal system was completely absorbed into the English system under English Common Law and both the English Lords who had been granted Welsh land by Edward I and their native Welsh contemporaries became part of the English Peerage. As a result of this creation of a modern sovereign state of England, fixed surnames became hereditary amongst the Welsh gentry, a custom which was slowly to spread amongst the rest of the Welsh people, although the patronymic naming system could still be found in areas of rural Wales until the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The change from patronymic to fixed surnames meant the Welsh people had a limited stock of names to choose from, which was not helped by the decline in the number of baptismal names following the Protestant Reformation. Many of the new fixed surnames still incorporated the “ap” or ab to create new names such as Powell (taken from ap Hywel) and Bevan (taken from ab Evan). However, the most common method for creating surnames came from adding an ‘s’ to the end of a name, whereby the most common modern Welsh surnames such as Jones, Williams, Davies and Evans originated. In an effort to avoid confusion between unrelated individuals bearing the same name, the nineteenth century saw a rise in the number of double barrelled surnames in Wales, often using the mother’s maiden name as a prefix to the family name.

Whilst most Welsh surnames are now fixed family names which have been passed down through the generations there has been a resurgence of the patronymic naming system amongst those Welsh speakers keen to preserve a patriotic history of Wales. In the last decade, in a return to a more independent Wales, the Government of Wales Act 2006 saw the creation of the Welsh Assembly Government and delegation of power from Parliament to the Assembly, giving the Assembly the authority to create “Measures”, or Welsh Laws, for the first time in over 700 years. Although for the sake of the Welsh telephone book let’s hope the patronymic naming system doesn’t make a complete comeback!

The Cornish Language

This March 5th, mark St Piran’s Day, the national day of Cornwall, by wishing your neighbours “Lowen dydh sen Pyran!”.

According to the 2011 census data, there are 100 different languages spoken in England and Wales, ranging from the well known to almost forgotten. The census results show that 33 people on the Isle of Man said their main language was Manx Gaelic, a language officially recorded as extinct in 1974, and 58 people said Scottish Gaelic, spoken mainly in the Highlands and western Islands of Scotland. Over 562,000 people named Welsh as their main language.

Whilst many British people are aware of Welsh and Gaelic, few have heard of ‘Cornish’ as a separate language, despite the fact that on the census, as many as 557 people listed their main language as ‘Cornish’.

So why do the Cornish have their own language? To understand, we have to look at the history of this relatively remote, south western region of England.

Cornwall has long felt a closer affinity with the European Celtic nations than with the rest of England. Derived from the Brythonic languages, the Cornish language has common roots with both Breton and Welsh.

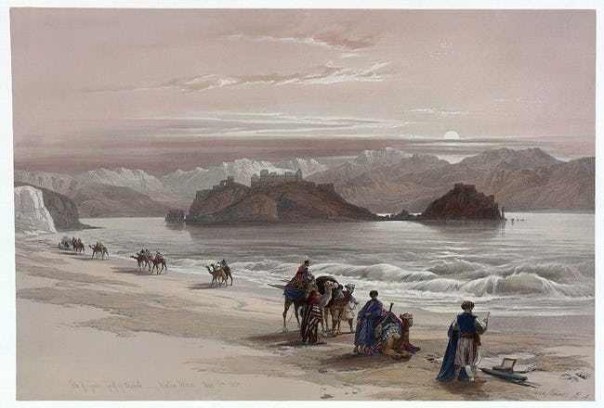

The words ‘Cornwall’ and ‘Cornish’ are derived from the Celtic Cornovii tribe who inhabited modern-day Cornwall prior to the Roman conquest. The Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain in the 5th to 6th centuries pushed the Celts further to the western fringes of Great Britain. It was however the influx of Celtic Christian missionaries from Ireland and Wales in the 5th and 6th centuries that shaped the culture and faith of the early Cornish people.

These missionaries, many of whom were later venerated as saints, settled on the shores of Cornwall and began converting small groups of local people to Christianity. Their names live on today in Cornish place names, and over 200 ancient churches are dedicated to them.

The Cornish were often at war with the West Saxons, who referred to them as the Westwalas (West Welsh) or Cornwalas (the Cornish). This continued until 936, when King Athelstan of England declared the River Tamar the formal boundary between the two, effectively making Cornwall one of the last retreats of the Britons, thus encouraging the development of a distinct Cornish identity. (Pictured right: Anglo-Saxon warrior)

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Cornish were seen as a separate race or nation, distinct from their neighbours, with their own language, society and customs. The unsuccessful Cornish Rebellion of 1497 illustrates the Cornish feeling of ‘being separate’ from the rest of England.

During the early years of the new Tudor dynasty, the pretender Perkin Warbeck (who declared himself to be Richard, Duke of York, one of the Princes in the Tower), was threatening King Henry VII’s crown. With the support of the King of Scots, Warbeck invaded the north of England. The Cornish were asked to contribute to a tax to pay for the King’s campaign in the north. They refused to pay, as they considered the campaign had little to do with Cornwall. The rebels set out from Bodmin in May 1497, reaching the outskirts of London on June 16th. Some 15,000 rebels faced Henry VII’s army at the Battle of Blackheath; around 1,000 of the rebels were killed and their leaders put to death.

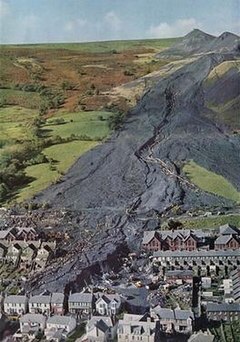

The Prayer Book Rebellion against the Act of Uniformity of 1549 was another example of the Cornish standing up for their culture and language. The Act of Uniformity outlawed all languages except English from Church services. The rebels declared that they wanted a return to the old religious services and practices, as some Cornishmen did not understand English. Over 4,000 people in the South West of England protested and were massacred by King Edward VI’s army at Fenny Bridges, near Honiton. This spread of English into the religious lives of the Cornish people is seen as one of the main factors in the demise of Cornish as the common language of the Cornish people.

As the Cornish language disappeared, so the people of Cornwall underwent a process of English assimilation.

However a Celtic revival which started in the early 20th century has revitalised the Cornish language and the Cornish Celtic heritage. An increasing number of people are now studying the language. Cornish is taught in many schools and there is a weekly bilingual programme on BBC Radio Cornwall. In 2002 the Cornish language was granted official recognition under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

The Cornish language even appears in the film and the book, Legends of the Fall by American author Jim Harrison, which depicts the lives of a Cornish American family in the early 20th century.

Here are a few examples of everyday phrases in Cornish:

Good Morning: “Metten daa”

Good Evening: “Gothewhar daa”

Hello: “You”

Goodbye: “Anowre”

Yorkshire Dialect

Did you know that August 1st is Yorkshire Day? To celebrate, we thought we’d share some great Yorkshire words and phrases with you.

Much of the Yorkshire dialect has its roots in Old English and Old Norse, and is called Broad Yorkshire or Tyke. Rather confusingly, someone born and bred in Yorkshire is also called a tyke.

Examples of the Yorkshire dialect can be found in literary works such as ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Emily Bronte and Charles Dickens’ novel ‘Nicholas Nickleby’. The reader will notice that in Broad Yorkshire, ‘ye’, ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ are used instead of ‘you’ and the word ‘the’ is shortened to t’.

Many people not from God’s Own County will consider the Yorkshire dialect as, shall we say, a little lugubrious. Indeed the words do seem to lend themselves to a Les Dawson-style of delivery.

‘Owt and Nowt

Two words used a lot in Yorkshire, meaning something and nothing. They are traditionally pronounced to rhyme with ‘oat’ rather than ‘out’, for example ‘Yah gooid fur nowt’ (you’re good for nothing). The old Yorkshire expression, “If there’s owt for nowt, I’ll be there with a barrow” would seem to bear out the impression that some people have of Yorkshire people, that they are careful, or tight, with their money. As the ‘Yorkshireman’s Motto’ goes:

‘Ear all, see all, say nowt;

Eat all, sup all, pay nowt;

And if ivver tha does owt fer nowt –

Allus do it fer thissen.

(Hear all, see all, say nothing; eat all, drink all, pay nothing, and if ever you do something for nothing, always do it for yourself).

‘Appen

This word will be very familiar to fans of Emmerdale, as a favourite utterance by most of the characters in the early days of the soap, in particular Amos Brealry and Annie Sugden. It means ‘perhaps’ or ‘possibly’ and is often preceded by ‘Aye’(yes) as in ‘Aye, ‘appen’. Other useful Yorkshire phrases include ‘Appen that’s it’ (that’s possibly true) and ‘Appen as not an maybe’ (you’re probably right).

‘Eee by gum

No, this isn’t just gibberish, it does actually mean something, although there is no direct translation. It means something like ‘Gosh!’, ‘Cor’, ‘Oh my God’ or ‘By gum’.

Nah then

This is often heard when friends greet each other and is used like a casual ‘hello’ or ‘hi’. Another way to say hello in Yorkshire would be ‘Eh up’.

Middlin’, Nobbut Middlin’, Fair t’ Middlin’

Again, these are expressions with no exact translation. Often heard in response to the question ‘Ow do’ (How are you), ‘middlin’ or ‘fair t’middlin’ would mean ’I’m ok’. ‘Nobbut middlin’ means less than middlin’, so more like ‘just alright’.

Middlin’ is not to be confused with middin which refers to a muck heap, rubbish heap or even the outside loo!

So for example:

Nah then,’ow do? – Nobbut middlin’.

Now you’re fluent in Yorkshire!

Reference

- The History of Welsh Surnames, Historic UK, by Ben Johnson https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/The-History-of-Welsh-Surnames/

- The Cornish Language, Historic UK, by Ben Johnson https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/The-Cornish-Language/

- The Yorkshire Dialect, Historic UK, by Ellen Castelow https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Yorkshire-Dialect/