The Catholic Church claims that it is the oldest Christian Church in the world, dating back to Jesus himself. In the time that the Church has been on earth, many unusual traditions have arisen. While most of them seem perfectly normal to Catholics, to non-Catholics they often seem outright bizarre. This is a list of the ten most bizarre aspects of Catholicism. In no particular order

10: Stigmata

Stigmata is when a person has unexplained wounds on their body that coincide with the traditional wounds that Christ had. In some cases the wounds can appear in only one or two of the areas, but there have been instances of it occurring in all five places that Christ was wounded. The wounds can cause considerable pain which has been known to worsen on certain religious feast days. There have been occasional cases of falsified stigmata in the past and some people claim that even those which are not proven to be falsified are somehow part of a hoax.

The photograph above is of Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (Canonized in 2002) who is the most recent stigmatic in the Catholic Church. Saint Pio is the latest in a long line of famous stigmatics – the most famous of whom is probably St Francis of Assisi. Writing to his spiritual director, Saint Pio said:

Then last night something happened which I can neither explain nor understand. In the middle of the palms of my hands a red mark appeared, about the size of a penny, accompanied by acute pain in the middle of the red marks. The pain was more pronounced in the middle of the left hand, so much so that I can still feel it. Also under my feet I can feel some pain.

It is also alleged that Saint Pio was able to bi-locate (appear in two places at once) and to read the sins on a person’s soul

9: The Cilice

A cilice is an item worn on the body to inflict pain or discomfort for the sake of penance (remorse for your past actions). Originally a cilice was an undergarment made of rough hair (such as a hairshirt) or cloth. In recent times it has been seen as more discreet to wear a chain which has spikes on it. Contrary to popular belief, the cilice does not break the skin – it merely causes discomfort. It is usually worn around the thigh.

The Catholic Encylopedia of 1913 says:

“In modern times the use of the hairshirt [(cilice)] has been generally confined to the members of certain religious orders. At the present day only the Carthusians and Carmelites wear it by rule; with others it is merely a matter of custom or voluntary mortification.”

In recent years the cilice has gained a great deal of publicity due to the book The Da Vinci Code in which it is worn by the main antagonist of the story – though in the story it is exaggeratedly described as causing wounds. Wearing the cilice has always been an optional practice for Catholics. Some famous people in the past to have worn them are Saint Thomas More and Saint Patrick.

8: The Flagrum

The Flagrum is a type of scourge with small hard objects attached to the length of its cords. It is traditionally used to whip oneself (self-flagellation) and is most commonly found in conservative religious orders. The flagrum is held in one hand and thrown over the shoulder in order to cause the cords to strike the flesh. The purpose of self-flagellation is voluntary penance and mortification of the flesh (a safeguard against committing further sins).

The most famous Saint to use the flagrum is probably Saint John Vianney, who would give his parishoners very light penances in confession and then flog himself in privacy for their benefit (it is believed by Catholics that acts of penance can be offered for the sins of other living people or the souls of the dead). When Saint John Vianney died, the walls of his bedroom had spatterings of blood on them from his extreme use of the flagrum.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:

“St. Peter Damian (died 1072) […] wrote a special treatise in praise of self-flagellation; though blamed by some contemporaries for excess of zeal, his example and the high esteem in which he was held did much to popularize the voluntary use of the scourge or “discipline” as a means of mortification and penance.”

Most Catholics who practice this form of discipline will not admit it publicly as it would be seen as a lack of humility that could lead to the sin of pride.

7: Confraternities of the Cord

The third, (and final) of the penance-related objects, the Confraternities of the Cord are groups who wear a knotted cord around their waist as a form of penance and in order to help prevent future sins. The cord can be worn loosely in remembrance of the Saint for whom the cord is named, or it can be worn tight enough to cause pain, as has been the case with numerous saints in history.

St Joseph, St Francis, St Thomas, and St Augustine, St Nicholas, and St Monica all have Confraternities of the Cord named after them. The Catholic Encylopedia says:

In the early Church virgins wore a cincture as a sign and emblem of purity, and hence it has always been considered a symbol of chastity as well as of mortification and humility. The wearing of a cord or cincture in honour of a saint is of very ancient origin, and we find the first mention of it in the life of St. Monica.

The various confraternities differ in the number of knots on the cord.

6: Relics

Relic of St Augustine

Relics are objects related to Saints. There are three categories of relics (from wikipedia):

1st Class

Items directly associated with the events of Christ’s life (manger, cross, etc.), or the physical remains of a saint (a bone, a hair, a limb, etc.). Traditionally, a martyr’s relics are often more prized than the relics of other saints. Also, some saints relics are known for their extraordinary incorruptibility and so would have high regard. It is important to note that parts of the saint that were significant to that saint’s life are more prized relics. For instance, King St. Stephen of Hungary’s right forearm is especially important because of his status as a ruler. A famous theologian’s head may be his most important relic.

2nd Class

An item that the saint wore (a sock, a shirt, a glove, etc.) Also included is an item that the saint owned or frequently used, for example, a crucifix, book etc. Again, an item more important in the saint’s life is thus a more important relic.

3rd Class

Anything which has touched a first or second class relic of a saint.

In order to prevent abuses, Catholic Church law (Canon Law) forbids the sale of Relics (Can. 1190 §1). Catholics venerate relics in the same way as they venerate images, statues, and saints. This is often confused for idol worship, but veneration is actually the act of giving respect, rather than the act of worshipping which is forbidden. By canon law there must be a relic in the altar stone of any altar in a Catholic Church upon which Mass is to be offered.

5: Indulgences

Catholics believe that when a person sins, they have two punishments to suffer – eternal (Hell) and temporal (punishment by suffering on earth or in Purgatory). Indulgences are special actions that a person can perform in order to reduce or remove the temporal punishment they are owed. The idea behind it is that certain acts of holiness can take the place of punishment. Indulgences must be declared by the Pope.

There are two types of indulgence: Plenary (removes all temporal punishment) and partial (removes some punishment). A partial indulgence can be for a specific number of days or years. Some indulgences only apply to the souls in Purgatory but any personal indulgences can also be offered for those souls, rather than your own. An example of an indulence is: “An indulgence, applicable only to the Souls in Purgatory, is granted to the faithful, who devoutly visit a cemetery and pray, even if only mentally, for the departed. The indulgence is plenary each day from the 1st to the 8th of November; on other days of the year it is partial.” (from the Enchiridion of Indulgences).

During the middle ages, a number of Bishops and Priests, seeking to make money, told people that they could pay for indulgences. This abuse partly contributed to the sparking off of the protestant reformation. While the Catholic Church tried to suppress this behavior, it took a great deal of time for the traffic in indulgences to stop completely.

It is quite common for the Pope to announce new indulgences from time to time, to mark special occasions – such as the Jubilee in which Pope John Paul II granted a plenary indulgence.

4: The Real Presence

The Real Presence is the term used to describe the bread and wine in a Catholic Mass. Catholics believe that after the words of consecration have been spoken by the Priest, the bread (host) and wine change their substance to become the body and blood of Jesus. It is considered by Catholics, therefore, to be appropriate to worship and adore the changed objects. This is often seen as idol worship by non-Catholics as they do not believe the change of substance has occurred.

Because of this belief, Catholics have a special ceremony called Benediction, in which a consecrated host is placed in an ornate case called a monstrance and the people are blessed with it and kneel and pray before it. you can see an image of Pope Benedict XVI blessing people with a monstrance here.

An interesting side note is that it is believed that the modern term “hocus pocus” comes from an aberration of the words used by a priest at the moment of the consecration, in which he says: “Hoc est enim corpus Meum” meaning “for this is My body”.

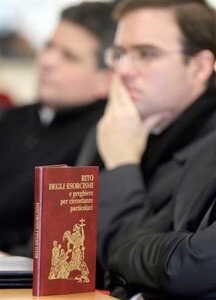

3: Exorcism

Exorcism is the practice of evicting demons or other evil spiritual entities from a person or place which they are believed to have possessed (taken control of). Solemn exorcisms, according to the Canon law of the church, can only be exercised by an ordained priest (or higher prelate), with the express permission of the local bishop, and only after a careful medical examination to exclude the possibility of mental illness. The Catholic Encyclopaedia says:

“Superstition ought not to be confounded with religion, however much their history may be interwoven, nor magic, however white it may be, with a legitimate religious rite”

During the ritual of exorcism, the priest commands the devils within the body of the afflicted to leave and uses a number of blessings with Holy Water and oils. To listen to two authentic recordings of exorcisms, visit the Top 10 Incredible Recordings. Of interesting note, the Catholic Church gave permission for a priest to appear in the film The Exorcist on the grounds that is was true to the methods used by the Church to determine whether an exorcism is warranted. A much more indepth article on exorcism including audio, videos, and images can be found here.

2: Papal Infallibility

Roman Catholics believe that, under certain circumstances, the pope is infallible (that is, he can not make a mistake). The Catholic Church defines three conditions under which the Pope is infallible:

I. The Pope must be making a decree on matters of faith or morals

II. The declaration must be binding on the whole Church

III. The Pope must be speaking with the full authority of the Papacy, and not in a personal capacity.

This means that when the Pope is speaking on matters of science, he can make errors (as we have seen in the past with issues such as Heliocentricity). However, when he is teaching a matter of religion and the other two conditions above are met, Catholics consider that the decree is equal to the Word of God. It can not contradict any previous declarations and it must be believed by all Catholics. Catholics believe that if a person denies any of these solemn decrees, they are committing a mortal sin – the type of sin that sends a person to hell. Here is an example of an infallible decree from the Council of Trent (under Pope Pius V):

If anyone denies that in the sacrament of the most Holy Eucharist are contained truly, really and substantially the body and blood together with the soul and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, and consequently the whole Christ, but says that He is in it only as in a sign, or figure or force, let him be anathema.

The last section of the final sentence “let him be anathema” is a standard phrase that normally appears at the end of an infallible statement. It means “let him be cursed”.

1: The Scapular

The Scapular is a type of necklace worn by many Catholics. It is worn across the scapular bones (hence its name) and it consists of two pieces of wool connected by string. One piece of wool rests on the back while the other piece rests on the chest. When a Catholic wishes to wear the scapular, a Priest says a set of special prayers and blesses the scapular. This only occurs the first time a person wears one.

For wearing the scapular, Catholics believe that Mary, the mother of Jesus, will ensure that they do not die a horrible death (for example by fire or drowning) and that they will have access to a priest for confession and the last rites before they die. As a condition for wearing the scapular and receiving these benefits, the Catholic must say certain prayers every day. The Catholic Encyclopedia says this:

According to a pious tradition the Blessed Virgin appeared to St. Simon Stock at Cambridge, England, on Sunday, 16 July, 1251. In answer to his appeal for help for his oppressed order, she appeared to him with a scapular in her hand and said: “Take, beloved son this scapular of thy order as a badge of my confraternity and for thee and all Carmelites a special sign of grace; whoever dies in this garment, will not suffer everlasting fire. It is the sign of salvation, a safeguard in dangers, a pledge of peace and of the covenant”.

The brown scapular, known as the Scapular of Our Lady of Mount Carmel is the most commonly worn scapular, though others do exist. When the scapular is worn out it is either buried or burnt and a new one is worn in its place.

Reference

- Top 10 Bizarre Aspects of Catholicism, ListVerse, 14 November 2019, by Jamie Frater https://listverse.com/2007/09/12/top-10-bizarre-aspects-of-catholicism/