Islam once considered homosexuality to be one of the most normal things in the world.

The Ottoman Empire, the seat of power in the Muslim world, didn’t view lesbian or gay sex as taboo for centuries. They formally ruled gay sex wasn’t a crime in 1858.

But as Christians came over from the west to colonize, they infected Islam with homophobia.

The truth is many Muslims alive today believe the prophet Muhammad supported and protected sexual and gender minorities.

But go back to the beginning, and you’ll see there is far mre homosexuality in Islam than you might have ever thought before.

1 Ancient Muslim borrowed culture from the boy-loving Ancient Greeks

The Islamic empires, (Ottoman, Safavid/Qajar, Mughals), shared a common culture. And it shared a lot of similarities with the Ancient Greeks.

Persianate cultures, all of them Muslim, dominated modern day India and Arab world. And it was very common for older men to have sex with younger, beardless men. These younger men were called ‘amrad’.

Once these men had grown his beard (or ‘khatt’), he then became the pursuer of his own younger male desires.

And in this time, once you had fulfilled your reproductive responsibilities as a man you could do what you like with younger men, prostitutes and other women.

Society completely accepted this, at least in elite circles. Iranian historian Afsaneh Najmabadi writes how official Safavid chroniclers would describe the sexual lives of various Shahs, the ruling class, without judgment.

There was some judgment over ‘mukhannas’. These were men (some researchers consider them to be transgender or third gender people) who would shave their beards as adults to show they wished to continue being the object of desire for men. But even they had their place in society. They would often be used as servants for prophets.

‘It wasn’t exactly how we would define homosexuality as we would today, it was about patriarchy,’ Ludovic-Mohamed Zahed, a gay imam who lives in Marseilles, France, told GSN.

‘It was saying, “I’m a man, I’m a patriarch, I earn money so I can rape anyone including boys, other slaves and women.” We shouldn’t idealize antique culture.’

2 Paradise included male virgins, not just female ones

There is nowhere in the Qu’ran that states the ‘virgins’ in paradise are only female.

The ‘hur’, or ‘houris’, are female. They have a male counterpart, the ‘ghilman’, who are immortal young men who wait and serve people in paradise.

‘Immortal [male] youths shall surround them, waiting upon them,’ it is written in the Qu’ran. ‘When you see them, you would think they are scattered pearls.’

Zahed says you should look at Ancient Muslim culture with the same eyes as Ancient Greek culture.

‘These amrads are not having sex in a perfectly consenting way because of power relationships and pressures and so on.

‘However, it’s not as heteronormative as it might seem at first. There’s far more sexual diversity.’

3 Sodom and Gomorrah is not an excuse for homophobia in Islam

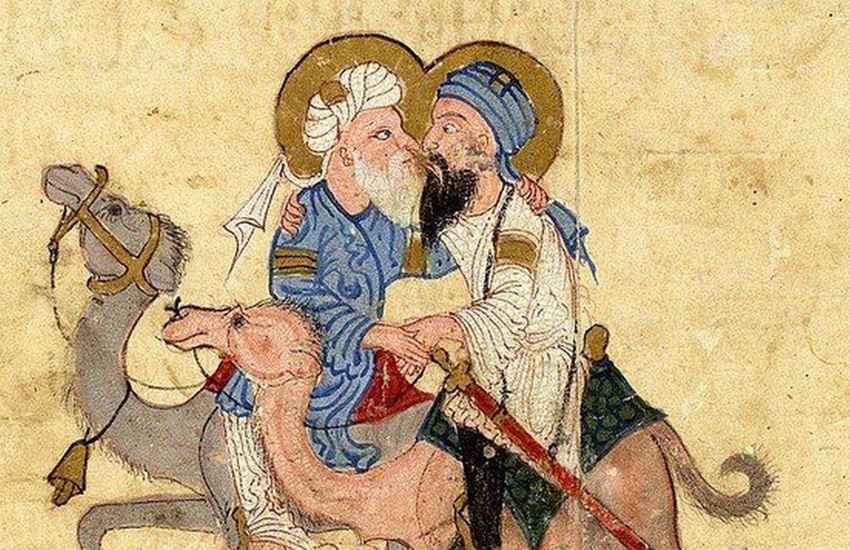

Like the Bible, the Qu’ran tells the story of how Allah punished the ancient inhabitants of the city of Sodom.

Two angels arrive at Sodom, and they meet Lot who insists they stay the night in his house. Then other men learn about the strangers, and insist on raping them.

While many may use this as an excuse to hate gay people, it’s not. It’s about Allah punishing rape, violence and refusing hospitality.

Historians often rely on literary representations for evidence of history. And many of the poems from ancient Muslim culture celebrate reciprocal love between two men. There are also factual reports saying it was illegal to force your way onto a young man.

The punishment for a rape of a young man was caning the feet of the perpetrator, or cutting off an ear, Najmabadi writes. Authorities are documented as carrying these punishments out in Qajar Iran.

4 Lesbian sex used as a ‘cure’

Fitting a patriarchal society, we know very little about the sex lives of women in ancient Muslim culture.

But ‘Sihaq’, translated literally as ‘rubbing’, is referenced as lesbian sex.

Sex between two women was decriminalized in the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, probably because it was deemed to have very little importance.

Physicians believed lesbianism developed from a hot itch on a woman’s vulva that could only be soothed by another woman’s sexual fluid. This derived from Greek medicine.

Much later, the 16th century Italian scientist Prosper Alpini claimed the hot climate caused ‘excessive sexual desire and overeating’ in women. This caused a humor imbalance that caused illnesses, like ‘lesbianism’. He recommended bathing to ‘remedy’ this. However, because men feared women were having sex with other women at private baths, many husbands tried to restrict women from going.

5 Lesbian ‘marriage’ and legendary couples

In Arabic folklore, al-Zarqa al-Yamama (‘the blue-eyed woman of Yamama’) fell in love with Christian princess Hind of the Lakhmids. When al-Zarqa, who had the ability to see events in the future, was crucified, it was said the princess cut her hair and mourned until she died.

Many books, especially in the 10th century, celebrated lesbian couples. Sapphic love features in the Book of Salma and Suvad; the Book of Sawab and Surur (of Justice and Happiness); the Book of al-Dahma’ and Nisma (of the Dark One and the Gift from God).

‘In palaces, there is evidence hundreds of women established some kind of contract. Two women would sign a contract swearing to protect and care for one another. Almost like a civil partnership or a marriage,’ Zahed said.

‘Outside of these palaces, this was also very common. There was a lot of Sapphic poetry showing same-sex love.’

As Europeans colonized these countries, depictions of lesbian love changed.

Samar Habib, who studied Arabo-Islamic texts, says the Arab epic One Thousand and One Nights proves this. He claims some stories in this classic show non-Muslim women preferred other women as sexual partners. But the ‘hero’ of the tale converts these women to Islam, and to heterosexuality.

6 Muhammad protected trans people

‘Muhammad housed and protected transgender or third gender people,’ Zahed said. ‘The leader of the Arab-Muslim world welcomed trans and queer people into his home.

‘If you look at the traditions some use to justify gay killings, you find much more evidence – clear evidence – that Muhammad was very inclusive.

‘He was protecting these people from those who wanted to beat them and kill them.’

7 How patriarchy transformed Islam

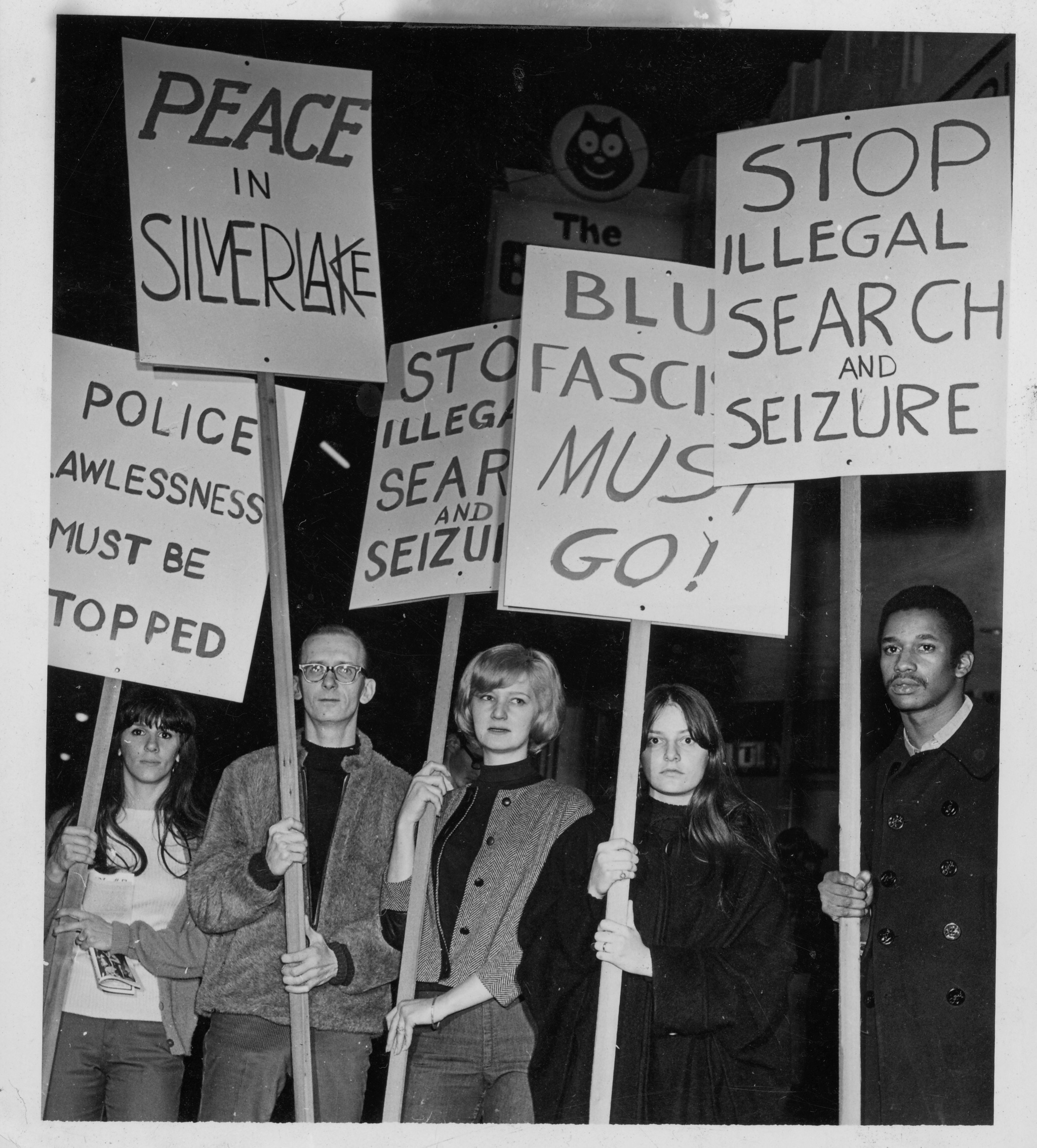

Europeans forced their way into the Muslim world, either through full on colonialism, like in India or Egypt, or economically and socially, like in the Ottoman Empire.

They pushed their cultural practices and attitudes on to Muslims: modern Islamic fundamentalism flourished.

While the Ottoman Empire resisted European culture at first, hence gay sex being allowed in 1858, nationalization soon won out. Twelve years later, in 1870, India’s Penal Code declared gay sex a crime. LGBTI Indians finally won against this colonial law in 2018.

But what is it like to be colonized? And why did homophobia get so much more extreme?

‘With the west coming in and colonizing, they think [Muslims] are lazy and passive and weak,’ Zahed said.

‘As Arab men, we have to prove we are more powerful and virile and manly. Modern German history is like that, showing how German nationalization rose after [defeat in] the First World War.

‘It’s tribalism, it’s the same problem. It’s about killing everyone against my tribe. I’m going to kill the weak. I’m going to kill anyone who doesn’t fulfil this aggressive nationalistic stereotype.’

Considering the male-dominant society already existed, it was easy for the ‘modern’ patriarchy to end up suppressing women and criminalizing LGBTI lives.

‘In the early 20th century, Arabs were ashamed of their ancient history,’ Zahed added. ‘They tried to purify it, censor it, to make it more masculine. There had to be nothing about femininity, homosexuality or anything. That’s how we got to how are today.’

8 What would Muhammad think about LGBTI rights?

Muhammad protected sexual and gender minorities, supporting those at the fringes of society.

And if Muslims are to follow in the steps of early Islamic culture and the prophet’s life, there is no reason Islam should oppose LGBTI people.

For Zahed, an imam, this is what he considers a true Muslim.

‘What should we do if we call ourselves Muslims now? Defend human rights, diversity and respect identity. If we trust the tradition, he was proactively defending sexual and gender minorities, and human rights.’

Reference

- The secret gay history of Islam, Gay Star News, 13 October 2017, by Joe Morgan https://www.gaystarnews.com/article/secret-gay-history-islam/#gs.xvedml