Ellie Cawthorne talks to Angela Steidele about the 19th-century gay pioneer Anne Lister | Complements the eight-part BBC One drama Gentleman Jack

At 2am one night in the 1890s, amateur code-breakers John Lister and Arthur Burrell were hard at work. The pair had been up for hours poring over mysterious documents John had inherited, among swathes of ageing ledgers and paperwork, when he had become master of Shibden Hall near Halifax. Entitled the ‘Diaries and Journals of Mrs Lister’, the 24 volumes documented the business affairs, social life and travels of one of Shibden Hall’s previous owners, Anne Lister (1791–1840), who had inherited the house in 1826.

While John, a distant relation of Anne, found the diaries diverting enough, what really intrigued him were large sections tantalisingly concealed in code. He enlisted the help of Burrell, an antiquarian, and the pair set to work deciphering Anne’s code of numerical figures, Greek letters and invented symbols.

Once they had cracked it, however, “the part written in cipher turned out to be entirely unpublishable…” What had been revealed was, in the words of Arthur Burrell, “an intimate account of homosexual practices among Miss Lister and her many ‘friends’; hardly any one of them escaped her”. Burrell was so appalled by the “unsavoury” discovery that he advised his friend to burn the diaries immediately.

Thankfully, John resisted the urge to fling the volumes directly onto the fire. Instead, he sealed them into a small chamber in Shibden Hall, keen to prevent anyone uncovering such salacious family secrets. Concealed behind wood panelling, they would go undiscovered until after his death in 1933.

Sexual adventures

Although Lister and Burrell may not have appreciated it at the time, the diaries they had decoded that night would go on to become a seminal source of British LGBTQ history – one that would force historians to reassess lesbian relationships in the early 19th century.

Running to more than 4 million words, Anne Lister’s journals are densely packed with the minutiae of her everyday life. Yet buried between exhaustive entries on the political situation in Prussia, canal tolls and toenail cutting are extraordinary accounts of her romantic and sexual adventures with women.

Lister embarked on her career as a master of seduction while still at school, starting up a relationship with her friend and roommate Eliza Raine, who she later reflected was “the most beautiful girl I ever saw”. Sexual encounters with various female acquaintances followed. As Anne boasted in 1816: “The girls liked me and had always liked me. I had never been refused by anyone.” According to Angela Steidele, author of a new biography of Lister, “it was easy for Anne to find lovers because she was a very attractive character: charming, flattering, witty and well educated. She was the heart of every party and could talk you in or out of anything.”

The greatest passion documented in Anne’s diary comes from her relationship with Mariana Belcombe, the “mistress of [her] thoughts and hopes”. For almost 20 years, the pair were involved in an on-off love affair which continued even after Mariana married – an institution that Anne bitterly compared to legitimised prostitution. The relationship eventually broke down after Mariana became increasingly anxious about its true nature being uncovered, leaving Anne with a heart “almost agonised to bursting”.

Despite this crushing rejection, Anne maintained that she had as much right to love and companionship as anyone, and was not afraid to pursue it actively. “There is one thing that I wish for… one thing without which my happiness in this world seems impossible,” she wrote in 1832. “I was not born to live alone… in loving and being loved, I could be happy.”

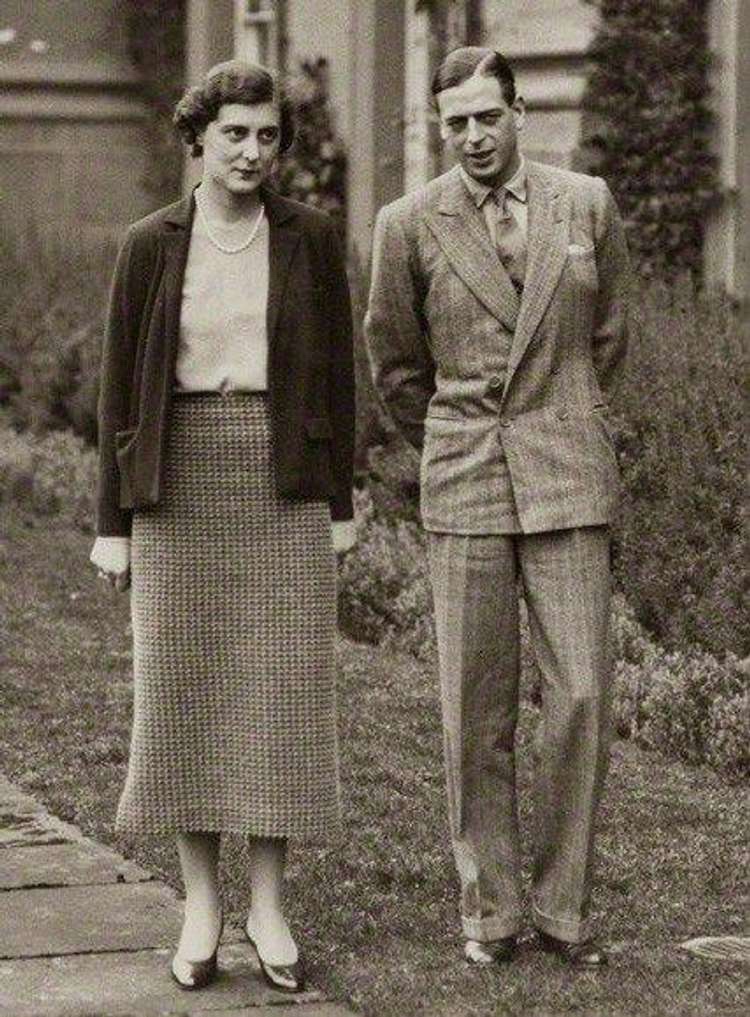

When she was in her early 40s, Anne began what would be her last – and arguably most significant – relationship, with Ann Walker, from a wealthy neighbouring family. Although she did not inspire the same passion as Mariana once had, Ann did meet many of the criteria of what Lister looked for in a partner: she was younger, pliable, obedient and well-off. “I shall think myself into being in love with her – I am already persuaded I like her well enough for comfort,” the cash-strapped Lister concluded in 1832. “Perhaps after all, she will make me happier than any of my former flames – at all rates we shall have money enough.”

Despite this somewhat lacklustre start, the pair embarked on a relationship. Walker moved in to Shibden Hall and, in 1834, the two women exchanged rings in York’s Holy Trinity Church. They took the Communion together, which they thought to be equivalent to marriage (180 years before same-sex marriages were legalised in England), though their union was not blessed by a priest.

Anne’s conquests were multiple, but “what is clear from reading her diaries is that the biggest love of Anne’s life was Anne herself”, says Steidele. “In fact, you could read these volumes as one long love letter to herself. She truly got lost in her diary, and was writing purely for her own satisfaction.”

And satisfaction really is the right word for it. Lister’s diary is extraordinarily candid in detailing her sexual encounters, going far beyond noting who she had seduced and when. Rather, her code conceals intimate descriptions of specific sexual acts and even keeps a tally of her number of orgasms. Assessments of each encounter are frank to the point of brusqueness – while one lover is praised for “know[ing] how to heighten the pleasure of our intercourse”, another is condemned as “dry as a stick”.

Physical acts

Such explicit details don’t just make the diaries compelling reading, says Steidele, it also gives them huge historical significance. “In earlier research on sexuality in the late 19th and 20th century, there was a legend that women never desired other women physically. The term that was often used was ‘romantic friendship’, implying that while some women enjoyed very close relationships, they never engaged in any physical acts.” Lister’s diaries however, act as the ‘missing link’ in British LGBTQ studies. By speaking directly of sex between women, they reveal the idea of ‘romantic friendship’ to be a false concept. This has led her writings to be hailed as the “Rosetta stone of lesbian history”.

“There have been homosexual acts throughout history, but what makes Lister different is her awareness of her own difference,” says Steidele. “Historians tend to say an awareness of homosexuality as an identity first emerged in the late 19th century, but Lister’s journals are an earlier proof of this development. That’s why she can be seen as Britain’s ‘first modern lesbian’.”

One lover is praised by Anne for “knowing how to heighten the pleasure of our intercourse”

It wasn’t only in her choice of lovers that Anne challenged the conventions of her time, but in her expression of gender too. She rejected the usual path laid out for women of her background, and was unafraid to send out strong signals of her difference. At a time when clothing was an important marker of identity, Lister chose to dress solely in black, adopting a self-consciously masculine appearance. This unconventional attire did not go unnoticed. She was referred to locally as ‘Gentleman Jack’, and wrote in 1818 that, “people generally remark as I pass along, how much I am like a man”.

Lister’s rejection of gender norms went far beyond clothing. As well as being a landowner at a time when few women owned property, she took a keen interest in business, taking on several ambitious, if not entirely profitable, entrepreneurial ventures. She established two coal mines (naming one the ‘Walker pit’ after her lover), ran a stone quarry and even launched a hotel in Halifax.

Her wealth and status as a gentlewoman undoubtedly offered Lister a degree of freedom unavailable to many women at the time. However, it did not render her completely immune against criticism of her unconventional lifestyle choices. She was mocked with anonymous letters, while a fake wedding announcement in the local paper congratulated Ann Walker on her marriage to a “Captain Tom Lister of Shibden Hall”.

Away from Shibden Hall, Anne embarked on numerous foreign adventures, hiking the Pyrenees and travelling as far as Azerbaijan. In fact, it was during one of these adventures that she died, succumbing to a fever at Kutaisi, Georgia in September 1840, aged 49. Ann Walker, who was travelling with Lister at the time, had her lover’s body embalmed and brought back to England. She was buried in Halifax, West Yorkshire.

Sparking controversy

A century later, following the death of Anne’s relative John, Shibden Hall fell to the Halifax Corporation, and Anne’s diaries were rescued from their hiding place. However, their contents were deemed far too scandalous for public consumption, and it would be several more decades until they were shared beyond a small group of archivists and librarians – a first edition wasn’t published until 1988.

More recently, interest in Lister and her diaries has sky-rocketed. In 2016, Shibden Hall was recognised as a “historic LGBTQ venue” by Historic England, and has become an important site of LGBTQ pilgrimage. This year sees Anne’s adventures being brought to life in an eight-part TV drama, Gentleman Jack, airing on BBC One from May.

In 2018, a plaque dedicated to Lister was unveiled at York’s Holy Trinity Church. Referring to Lister as a “gender-nonconforming entrepreneur”, it sparked anger by making no mention of the word ‘lesbian’. Following a petition, the plaque was reworded to describe Anne as a “lesbian and diarist”. In Steidele’s opinion, this is an important distinction. “While Lister did not directly refer to herself as a ‘lesbian’, her diary makes it clear that a big part of her identity was derived from her sexuality. There was no guilt, no self-hatred – Anne felt she too was God’s creation and that God had shaped her nature. This is really unique. That’s why it is so important to include the term ‘lesbian’ when we celebrate Anne with that plaque.”

Two centuries on, the diaries still hold lessons for today, argues Steidele. “In many ways we’re still fighting the same battles as Anne – for equal women’s and LGBTQ rights,” she says. “Anne didn’t accept any limitation placed on her by her sexuality and gender. She refused to believe in the natural inferiority of women, and insisted on living according to her own inclinations. I think that her courage in those convictions makes her an important role model.”

Reference

- The real ‘Gentleman Jack’: the secret life of Anne Lister, Britain’s ‘first modern lesbian’, History Extra, 29 May 2019, by Ellie Cawthorne https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/anne-lister-real-gentleman-jack-diary-code-history-secret-life-britain-first-modern-lesbian/