Battling the ‘homosexual agenda,’ the hard-line religious right has made a series of incendiary claims. But they’re just not true.

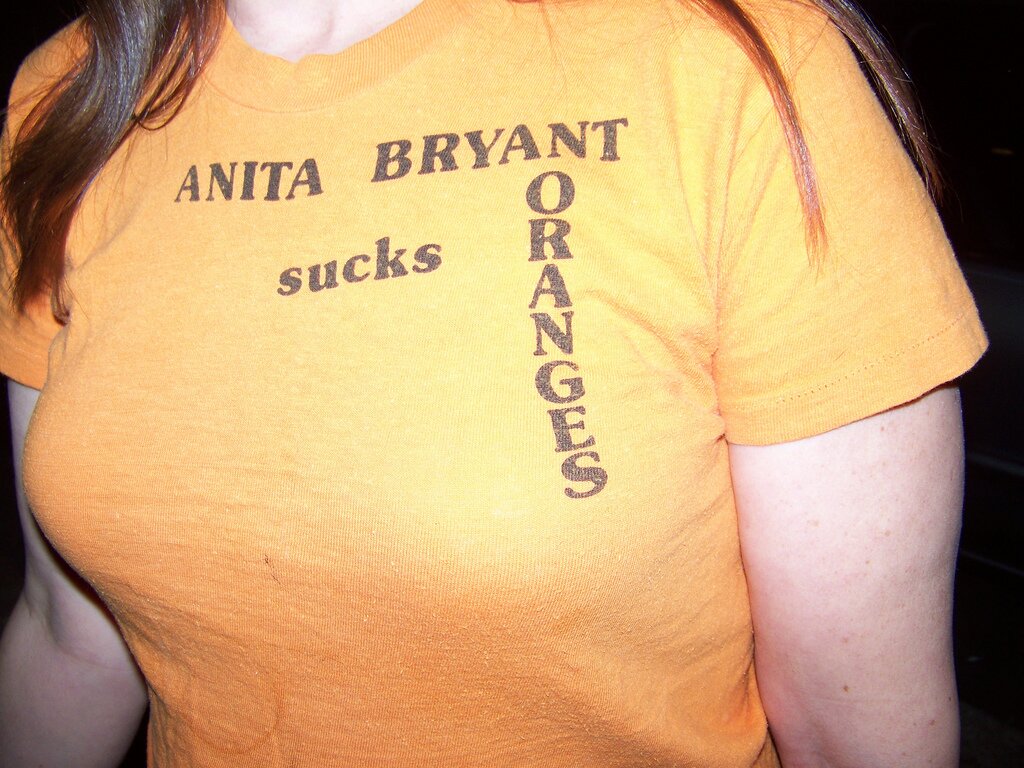

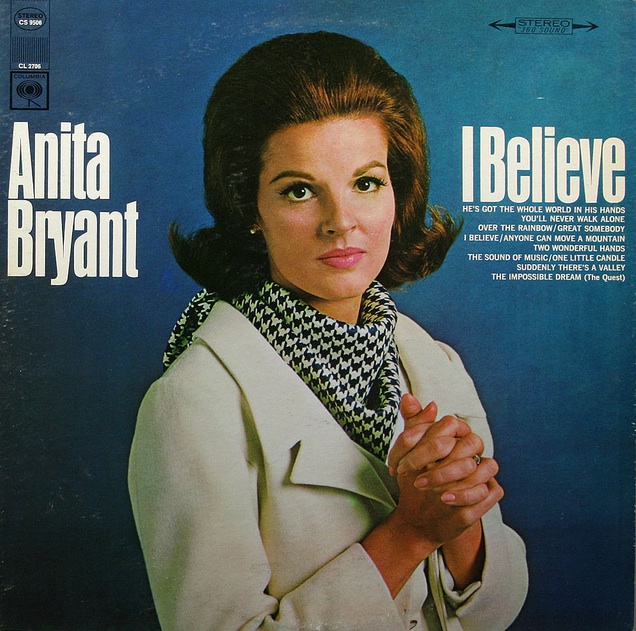

Ever since born-again singer and orange juice pitchwoman Anita Bryant helped kick off the contemporary anti-gay movement some 40 years ago, hard-line elements of the religious right have been searching for ways to demonize gay people — or, at a minimum, to find arguments that will prevent their normalization in society. For the former Florida beauty queen and her Save Our Children group, it was the alleged plans of gay men and lesbians to “recruit” in schools that provided the fodder for their crusade. But in addition to hawking that myth, the legions of anti-gay activists who followed have added a panoply of others, ranging from the extremely doubtful claim that sexual orientation is a choice, to unalloyed lies like the claims that gay men molest children far more than heterosexuals or that hate crime laws will lead to the legalization of bestiality and necrophilia. These fairy tales are important to the anti-gay right because they form the basis of its claim that homosexuality is a social evil that must be suppressed — an opinion rejected by virtually all relevant medical and scientific authorities. They also almost certainly contribute to hate crime violence directed at the LGBT community, which is more targeted for such attacks than any other minority group in America. What follows are 10 key myths propagated by the anti-gay movement, along with the truth behind the propaganda.

MYTH # 1

Gay men molest children at far higher rates than heterosexuals.

THE ARGUMENT

Depicting gay men as a threat to children may be the single most potent weapon for stoking public fears about homosexuality — and for winning elections and referenda, as Anita Bryant found out during her successful 1977 campaign to overturn a Dade County, Fla., ordinance barring discrimination against gay people. Discredited psychologist Paul Cameron, the most ubiquitous purveyor of anti-gay junk science, has been a major promoter of this myth. Despite having been debunked repeatedly and very publicly, Cameron’s work is still widely relied upon by anti-gay organizations, although many no longer quote him by name. Others have cited a group called the American College of Pediatricians (ACPeds) to claim, as Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council did in November 2010, that “the research is overwhelming that homosexuality poses a [molestation] danger to children.” A related myth is that same-sex parents will molest their children.

THE FACTS

According to the American Psychological Association, children are not more likely to be molested by LGBT parents or their LGBT friends or acquaintances. Gregory Herek, a professor at the University of California, Davis, who is one of the nation’s leading researchers on prejudice against sexual minorities, reviewed a series of studies and found no evidence that gay men molest children at higher rates than heterosexual men.

Anti-gay activists who make that claim allege that all men who molest male children should be seen as homosexual. But research by A. Nicholas Groth, a pioneer in the field of sexual abuse of children, shows that is not so. Groth found that there are two types of child molesters: fixated and regressive. The fixated child molester — the stereotypical pedophile — cannot be considered homosexual or heterosexual because “he often finds adults of either sex repulsive” and often molests children of both sexes. Regressive child molesters are generally attracted to other adults, but may “regress” to focusing on children when confronted with stressful situations. Groth found, as Herek notes, that the majority of regressed offenders were heterosexual in their adult relationships.

The Child Molestation Research & Prevention Institute notes that 90% of child molesters target children in their network of family and friends, and the majority are men married to women. Most child molesters, therefore, are not gay people lingering outside schools waiting to snatch children from the playground, as much religious-right rhetoric suggests.

Some anti-gay ideologues cite ACPeds’ opposition to same-sex parenting as if the organization were a legitimate professional body. In fact, the so-called college is a tiny breakaway faction of the similarly named, 60,000-member American Academy of Pediatrics that requires, as a condition of membership, that joiners “hold true to the group’s core beliefs … [including] that the traditional family unit, headed by an opposite-sex couple, poses far fewer risk factors in the adoption and raising of children.” The group’s 2010 publication Facts About Youth was described by the American Academy of Pediatrics as not acknowledging scientific and medical evidence with regard to sexual orientation, sexual identity and health, or effective health education. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, was one of several legitimate researchers who said ACPeds misrepresented the institutes’ findings. “It is disturbing to me to see special interest groups distort my scientific observations to make a point against homosexuality,” he wrote. “The information they present is misleading and incorrect.” Another critic of ACPeds is Dr. Gary Remafedi, a researcher at the University of Minnesota who wrote a letter to ACPeds rebuking the organization for misusing his research.

In spite of all this, the anti-LGBT right continues to peddle this harmful and baseless myth, which is probably the leading defamatory charge leveled against gay people.

MYTH # 2

Same-sex parents harm children.

THE ARGUMENT

Most hard-line anti-gay organizations are heavily invested, from both a religious and a political standpoint, in promoting the traditional nuclear family as the sole framework for the healthy upbringing of children. They maintain a reflexive belief that same-sex parenting must be harmful to children — although the exact nature of that supposed harm varies widely.

THE FACTS

No legitimate research has demonstrated that same-sex couples are any more or any less harmful to children than heterosexual couples.

The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry affirmed in 2013 that “[c]urrent research shows that children with gay and lesbian parents do not differ from children with heterosexual parents in their emotional development or in their relationships with peers and adults” and they are “not more likely than children of heterosexual parents to develop emotional or behavioral problems.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in a 2002 policy statement declared: “A growing body of scientific literature demonstrates that children who grow up with one or two gay and/or lesbian parents fare as well in emotional, cognitive, social, and sexual functioning as do children whose parents are heterosexual.” That policy statement was reaffirmed in 2009 and in 2013, when the AAP stated its support for civil marriage for same-gender couples and full adoption and foster care rights for all parents, regardless of sexual orientation.

The American Psychological Association (APA) noted in 2004 that “same-sex couples are remarkably similar to heterosexual couples, and that parenting effectiveness and the adjustment, development and psychological well-being of children is unrelated to parental sexual orientation.” In addition, the APA stated that “beliefs that lesbian and gay adults are not fit parents have no empirical foundation.” The next year, in 2005, the APA published a summary of research findings on lesbian and gay parents and reiterated that common negative stereotypes about LGBT parenting are not supported by the data.

Similarly, the Child Welfare League of America’s official position with regard to same-sex parents is that “lesbian, gay, and bisexual parents are as well-suited to raise children as their heterosexual counterparts.”

A 2010 review of research on same-sex parenting carried out by LiveScience, a science news website, found no differences between children raised by heterosexual parents and children raised by lesbian parents. In some cases, it found, children in same-sex households may actually be better adjusted than in heterosexual homes.

A 2013 preliminary study in Australia found that the children of lesbian and gay parents are not only thriving, but may actually have better overall health and higher rates of family cohesion than heterosexual families. The study is the world’s largest attempt to compare children of same-sex parents to children of heterosexual parents. The full study was published in June 2014.

The anti-LGBT right continues, however, to use this myth to deny rights to LGBT people, whether through distorting legitimate research or through “studies” conducted by anti-LGBT sympathizers, such as a 2012 paper popularly known as the Regnerus Study. University of Texas sociology professor Mark Regnerus’ paper purported to demonstrate that same-sex parenting harms children. The study received almost $1 million in funding from anti-LGBT think tanks, and even though Regnerus himself admitted that his study does not show what people say it does with regard to the “harms” of same-sex parenting, it continues to be peddled as “proof” that children are in danger in same-sex households. Since the study’s release, it has been completely discredited because of its faulty methodology and its suspect funding. In 2013, Darren Sherkat, a scholar appointed to review the study by the academic journal that published it, told the Southern Poverty Law Center that he “completely dismiss[es]” the study, saying Regnerus “has been disgraced” and that the study was “bad … substandard.” In spring 2014, the University of Texas’s College of Liberal Arts and Department of Sociology publicly distanced themselves from Regnerus, the day after he testified as an “expert witness” against Michigan’s same-sex marriage ban. The judge in that case, Bernard Friedman, found that Regnerus’ testimony was “entirely unbelievable and not worthy of serious consideration,” and ruled that Michigan’s ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional. Despite all this, the Regnerus Study is still used in the U.S. and abroad as a tool by anti-LGBT groups to develop anti-LGBT policy and laws.

MYTH # 3

People become homosexual because they were sexually abused as children or there was a deficiency in sex-role modeling by their parents.

THE ARGUMENT

Many anti-gay rights activists claim that homosexuality is a mental disorder caused by some psychological trauma or aberration in childhood. This argument is used to counter the common observation that no one, gay or straight, consciously chooses his or her sexual orientation. Joseph Nicolosi, a founder of the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality, said in 2009 that “if you traumatize a child in a particular way, you will create a homosexual condition.” He also has repeatedly said, “Fathers, if you don’t hug your sons, some other man will.”

A side effect of this argument is the demonization of parents of gay men and lesbians, who are led to wonder if they failed to protect a child against sexual abuse or failed as role models in some important way. In October 2010, Kansas State University family studies professor Walter Schumm released a related study in the British Journal of Biosocial Science, which used to be the Eugenics Review. Schumm argued that gay couples are more likely than heterosexuals to raise gay or lesbian children through modeling “gay behavior.” Schumm, who has also argued that lesbian relationships are unstable, has ties to discredited psychologist and anti-LGBT fabulist Paul Cameron, the author of numerous completely baseless “studies” about the alleged evils of homosexuality. Critics of Schumm’s study note that he appears to have merely aggregated anecdotal data, resulting in a biased sample.

THE FACTS

No scientifically sound study has definitively linked sexual orientation or identity with parental role-modeling or childhood sexual abuse.

The American Psychiatric Association noted in a 2000 fact sheet available on the Association of Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists, that dealing with gay, lesbian and bisexual issues, that sexual abuse does not appear to be any more prevalent among children who grow up and identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual than in children who grow up and identify as heterosexual.

Similarly, the National Organization on Male Sexual Victimization notes on its websitethat “experts in the human sexuality field do not believe that premature sexual experiences play a significant role in late adolescent or adult sexual orientation” and added that it’s unlikely that anyone can make another person gay or heterosexual.

Advocates for Youth, an organization that works in the U.S. and abroad in the field of adolescent reproductive and sexual health also has stated that sexual abuse does not “cause” heterosexual youth to become gay.

In 2009, Dr. Warren Throckmorton, a psychologist at the Christian Grove City College, noted in an analysis that “the research on sexual abuse among GLBT populations is often misused to make inferences about causation [of homosexuality].”

MYTH # 4

LGBT people don’t live nearly as long as heterosexuals.

THE ARGUMENT

Anti-LGBT organizations, seeking to promote heterosexuality as the healthier “choice,” often offer up the purportedly shorter life spans and poorer physical and mental health of gays and lesbians as reasons why they shouldn’t be allowed to adopt or foster children.

THE FACTS

This falsehood can be traced directly to the discredited research of Paul Cameron and his Family Research Institute, specifically a 1994 paper he co-wrote entitled “The Lifespan of Homosexuals.” Using obituaries collected from newspapers serving the gay community, he and his two co-authors concluded that gay men died, on average, at 43, compared to an average life expectancy at the time of around 73 for all U.S. men. On the basis of the same obituaries, Cameron also claimed that gay men are 18 times more likely to die in car accidents than heterosexuals, 22 times more likely to die of heart attacks than whites, and 11 times more likely than blacks to die of the same cause. He also concluded that lesbians are 487 times more likely to die of murder, suicide, or accidents than straight women.

Remarkably, these claims have become staples of the anti-gay right and have frequently made their way into far more mainstream venues. For example, William Bennett, education secretary under President Reagan, used Cameron’s statistics in a 1997 interview he gave to ABC News’ “This Week.”

However, like virtually all of his “research,” Cameron’s methodology is egregiously flawed — most obviously because the sample he selected (the data from the obits) was not remotely statistically representative of the LGBT population as a whole. Even Nicholas Eberstadt, a demographer at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, has called Cameron’s methods “just ridiculous.”

Anti-LGBT organizations have also tried to support this claim by distorting the work of legitimate scholars, like a 1997 study conducted by a Canadian team of researchers that dealt with gay and bisexual men living in Vancouver in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The authors of the study became aware that their work was being misrepresented by anti-LGBT groups, and issued a response taking the groups to task.

MYTH # 5

Gay men controlled the Nazi Party and helped to orchestrate the Holocaust.

THE ARGUMENT

This claim comes directly from a 1995 book titled The Pink Swastika: Homosexuality in the Nazi Party, by Scott Lively and Kevin Abrams. Lively is the virulently anti-gay founder of Abiding Truth Ministries and Abrams is an organizer of a group called the International Committee for Holocaust Truth, which came together in 1994 and included Lively as a member.

The primary argument Lively and Abrams make is that gay people were not victimized by the Holocaust. Rather, Hitler deliberately sought gay men for his inner circle because their “unusual brutality” would help him run the party and mastermind the Holocaust. In fact, “the Nazi party was entirely controlled by militaristic male homosexuals throughout its short history,” the book claims. “While we cannot say that homosexuals caused the Holocaust, we must not ignore their central role in Nazism,” Lively and Abrams add. “To the myth of the ‘pink triangle’ — the notion that all homosexuals in Nazi Germany were persecuted — we must respond with the reality of the ‘pink swastika.'”

These claims have been picked up by a number of anti-gay groups and individuals, including Bryan Fischer of the American Family Association, as proof that gay men and lesbians are violent and sick. The book has also attracted an audience among anti-gay church leaders in Eastern Europe and among Russian-speaking anti-gay activists in America.

THE FACTS

The Pink Swastika has been roundly discredited by legitimate historians and other scholars. Christine Mueller, professor of history at Reed College, did a 1994 line-by-line refutation of an earlier Abrams article on the topic and of the broader claim that the Nazi Party was “entirely controlled” by gay men. Historian Jon David Wynecken at Grove City College also refuted the book, pointing out that Lively and Abrams did no primary research of their own, instead using out-of-context citations of some legitimate sources while ignoring information from those same sources that ran counter to their thesis.

The myth that the Nazis condoned homosexuality sprang up in the 1930s, started by socialist opponents of the Nazis as a slander against Nazi leaders. Credible historians believe that only one of the half-dozen leaders in Hitler’s inner circle, Ernst Röhm, was gay. (Röhm was murdered on Hitler’s orders in 1934.) The Nazis considered homosexuality one aspect of the “degeneracy” they were trying to eradicate.

When Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers Party came to power in 1933, it quickly strengthened Germany’s existing penalties against homosexuality. Heinrich Himmler, Hitler’s security chief, announced that homosexuality was to be “eliminated” in Germany, along with miscegenation among the races. Historians estimate that between 50,000 and 100,000 men were arrested for homosexuality (or suspicion of it) under the Nazi regime. These men were routinely sent to concentration camps and many thousands died there.

Himmler expressed his views on homosexuality like this: “We must exterminate these people root and branch. … We can’t permit such danger to the country; the homosexual must be completely eliminated.”

MYTH # 6

Hate crime laws will lead to the jailing of pastors who criticize homosexuality and the legalization of practices like bestiality and necrophilia.

THE ARGUMENT

Anti-gay activists, who have long opposed adding LGBT people to those protected by hate crime legislation, have repeatedly claimed that such laws would lead to the jailing of religious figures who preach against homosexuality — part of a bid to gain the backing of the broader religious community for their position. Janet Porter of Faith2Action, for example, was one of many who asserted that the federal Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act — signed into law by President Obama in October 2009 — would “jail pastors” because it “criminalizes speech against the homosexual agenda.”

In a related assertion, anti-gay activists claimed the law would lead to the legalization of psychosexual disorders (paraphilias) like bestiality and pedophilia. Bob Unruh, a conservative Christian journalist who left The Associated Press in 2006 for the right-wing, conspiracist news site WorldNetDaily, said shortly before the federal law was passed that it would legalize “all 547 forms of sexual deviancy or ‘paraphilias’ listed by the American Psychiatric Association.” This claim was repeated by many anti-gay organizations, including the Illinois Family Institute.

THE FACTS

The claim that hate crime laws could result in the imprisonment of those who “oppose the homosexual lifestyle” is false. The First Amendment provides robust protections of free speech, and case law makes it clear that even a preacher who publicly suggested that gays and lesbians should be killed would be protected.

Neither do hate crime laws — which provide for enhanced penalties when persons are victimized because of their “sexual orientation” (among other factors) — “protect pedophiles,” as Janet Porter and many others have claimed. According to the American Psychological Association, sexual orientation refers to heterosexuality, homosexuality and bisexuality — not paraphilias such as pedophilia. Paraphilias, as defined (pdf; may require a different browser) by the American Psychiatric Association, are characterized by sexual urges or behaviors directed at non-consenting persons or those unable to consent like children, or that involve another person’s psychological distress, injury, or death.

Moreover, even if pedophiles, for example, were protected under a hate crime law — and such a law has not been suggested or contemplated anywhere — that would not legalize or “protect” pedophilia. Pedophilia is illegal sexual activity, and a law that more severely punished people who attacked pedophiles would not change that.

MYTH # 7

Allowing gay people to serve openly will damage the armed forces.

THE ARGUMENT

Anti-gay groups have been adamantly opposed to allowing gay men and lesbians to serve openly in the armed forces, not only because of their purported fear that combat readiness will be undermined, but because the military has long been considered the purest meritocracy in America (the armed forces were successfully racially integrated long before American civil society, for example). If gays serve honorably and effectively in this meritocracy, that suggests that there is no rational basis for discriminating against them in any way.

THE FACTS

Gays and lesbians have long served in the U.S. armed forces, though under the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy that governed the military between 1993 and 2011, they could not do so openly. At the same time, gays and lesbians have served openly for years in the armed forces of 25 countries (as of 2010), including Britain, Israel, South Africa, Canada and Australia, according to a report released by the Palm Center, a policy think tank at the University of California at Santa Barbara. The Palm Center report concluded that lifting bans against openly gay service personnel in these countries “ha[s] had no negative impact on morale, recruitment, retention, readiness or overall combat effectiveness.” Successful transitions to new policies were attributed to clear signals of leadership support and a focus on a uniform code of behavior without regard to sexual orientation.

A 2008 Military Times poll of active-duty military personnel, often cited by anti-gay activists, found that 10% of respondents said they would consider leaving the military if the DADT policy were repealed. That would have meant that some 228,000 people might have left the military the policy’s 2011 repeal. But a 2009 review of that poll by the Palm Center suggested a wide disparity between what soldiers said they would do and their actual actions. It noted, for example, that far more than 10% of West Point officers in the 1970s said they would leave the service if women were admitted to the academy. “But when the integration became a reality,” the report said, “there was no mass exodus; the opinions turned out to be just opinions.” Similarly, a 1985 survey of 6,500 male Canadian service members and a 1996 survey of 13,500 British service members each revealed that nearly two-thirds expressed strong reservations about serving with gays. Yet when those countries lifted bans on gays serving openly, virtually no one left the service for that reason. “None of the dire predictions of doom came true,” the Palm Center report said.

Despite the fact that gay men and lesbians have been serving openly in the military since September 2011, anti-LGBT groups continue to claim that openly gay personnel are causing problems in the military, including claims of sexual abuse by gay and lesbian soldiers of straight soldiers. The Palm Center refutes this claim, and in an analysis, found that repealing DADT has had “no overall negative impact on military readiness or its component dimensions,” including sexual assault. According to then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta in 2012, the repeal of DADT was being implemented effectively and was having no impact on readiness, unit cohesion or morale. Panetta also issued an LGBT Pride message in 2012.

MYTH # 8

Gay people are more prone to be mentally ill and to abuse drugs and alcohol.

THE ARGUMENT

Anti-LGBT groups want not only to depict sexual orientation as something that can be changed but also to show that heterosexuality is the most desirable “choice,” even if religious arguments are set aside. The most frequently used secular argument made by anti-LGBT groups in that regard is that homosexuality is inherently unhealthy, both mentally and physically. As a result, most anti-LGBT rights groups reject the 1973 decision by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to remove homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses. Some of these groups, including the particularly hard-line Traditional Values Coalition, claim that “homosexual activists” managed to infiltrate the APA in order to sway its decision.

THE FACTS

All major professional mental health organizations are on record as stating that homosexuality is not a mental disorder.

The American Psychological Association states that being gay is just as healthy as being straight, and noted that the 1950s-era work of Dr. Evelyn Hooker started to dismantle this myth. In 1975, the association issued a statement that said, in part, “homosexuality per se implies no impairment in judgment, reliability or general social and vocational capabilities.” The association has clearly stated in the past that “homosexuality is neither mental illness nor mental depravity. … Study after study documents the mental health of gay men and lesbians. Studies of judgment, stability, reliability, and social and vocational adaptiveness all show that gay men and lesbians function every bit as well as heterosexuals.”

The American Psychiatric Association states that (PDF; may not open in all browsers) homosexuality is not a mental disorder and that all major professional health organizations are on record as confirming that. The organization removed homosexuality from its official diagnostic manual in 1973 after extensive review of the scientific literature and consultation with experts, who concluded that homosexuality is not a mental illness.

Though it is true that LGBT people tend to suffer higher rates of anxiety, depression, and depression-related illnesses and behaviors like alcohol and drug abuse than the general population, that is due to the historical social stigmatization of homosexuality and violence directed at LGBT people, not because of homosexuality itself. Studies done during the past several years have determined that it is the stress of being a member of a minority group in an often-hostile society — and not LGBT identity itself — that accounts for the higher levels of mental illness and drug use.

Richard J. Wolitski, an expert on minority status and public health issues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, put it like this in 2008: “Economic disadvantage, stigma, and discrimination … increase stress and diminish the ability of individuals [in minority groups] to cope with stress, which in turn contribute to poor physical and mental health.”

Even as early as 1994, external stressors were recognized as a potential cause of emotional distress of LGBT people. A report presented by the Council on Scientific Affairs to the AMA House of Delegates Interim Meeting with regard to reparative (“ex-gay”) therapy noted that most of the emotional disturbance gay men and lesbians experience around their sexual identity is not based on physiological causes, but rather on “a sense of alienation in an unaccepting environment.”

In 2014, a study, conducted by several researchers at major universities and the Rand Corporation, found that LGBT people living in highly anti-LGBT communities and circumstances face serious health concerns and even premature death because of social stigmatization and exclusion. One of the researchers, Dr. Mark Hatzenbuehler, a sociomedical sciences professor at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, said that the data gathered in the study suggests that “sexual minorities living in communities with high levels of anti-gay prejudice have increased risk of mortality, compared to low-prejudice communities.”

Homosexuality is not a mental illness or emotional problem and being LGBT does not cause someone to be mentally ill, contrary to what anti-LGBT organizations say. Rather, social stigmatization and prejudice appear to contribute to health disparities in the LGBT population, which include emotional and psychological distress and harmful coping mechanisms.

MYTH # 9

No one is born gay.

THE ARGUMENT

Anti-gay activists keenly oppose the granting of “special” civil rights protections to gay people similar to those afforded black Americans and other minorities. But if people are born gay — in the same way that people have no choice as to whether they are black or white — discrimination against gay men and lesbians would be vastly more difficult to justify. Thus, anti-gay forces insist that sexual orientation is a behavior that can be changed, not an immutable characteristic.

THE FACTS

Modern science cannot state conclusively what causes sexual orientation, but a great many studies suggest that it is the result of both biological and environmental forces, not a personal “choice.” A 2008 Swedish study of twins (the world’s largest twin study) published in The Archives of Sexual Behavior concluded that “[h]omosexual behaviour is largely shaped by genetics and random environmental factors.” Dr. Qazi Rahman, study co-author and a leading scientist on human sexual orientation, said: “This study puts cold water on any concerns that we are looking for a single ‘gay gene’ or a single environmental variable which could be used to ‘select out’ homosexuality — the factors which influence sexual orientation are complex. And we are not simply talking about homosexuality here — heterosexual behaviour is also influenced by a mixture of genetic and environmental factors.” In other words, sexual orientation in general — whether homosexual, bisexual or heterosexual — is a mixture of genetic and environmental factors.

The American Psychological Association (APA) states that sexual orientation “ranges along a continuum,” and acknowledges that despite much research into the possible genetic, hormonal, social and cultural influences on sexual orientation, scientists have yet to pinpoint the precise causes of sexual orientation. Regardless, the APA concludes that “most people experience little or no sense of choice about their sexual orientation.” In 1994, the APA noted that “homosexuality is not a matter of individual choice” and that research “suggests that the homosexual orientation is in place very early in the life cycle, possibly even before birth.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics stated in 1993 (updated in 2004) that “homosexuality has existed in most societies for as long as recorded descriptions of sexual beliefs and practices have been available” and that even at that time, “most scholars in the field state that one’s sexual orientation is not a choice … individuals do not choose to be homosexual or heterosexual.”

There are questions about what specifically causes sexual orientation in general, but most current science acknowledges that it is a complex mixture of biological, environmental, and possibly hormonal factors but that no one chooses an orientation.

MYTH # 10

Gay people can choose to leave homosexuality.

THE ARGUMENT

If people are not born gay, as anti-gay activists claim, then it should be possible for individuals to abandon homosexuality. This view is buttressed among religiously motivated anti-gay activists by the idea that homosexual practice is a sin and humans have the free will needed to reject sinful urges.

A number of “ex-gay” religious ministries have sprung up in recent years with the aim of teaching gay people to become heterosexuals, and these have become prime purveyors of the claim that gays and lesbians, with the aid of mental therapy and Christian teachings, can “come out of homosexuality.” The now defunct Exodus International, the largest of these ministries, once stated, “You don’t have to be gay!” Meanwhile, in a more secular vein, the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality describes itself as “a professional, scientific organization that offers hope to those who struggle with unwanted homosexuality.”

THE FACTS

“Reparative” or sexual reorientation therapy — the pseudo-scientific foundation of the ex-gay movement — has been rejected by all the established and reputable American medical, psychological, psychiatric and professional counseling organizations. In 2009, for instance, the American Psychological Association adopted a resolution, accompanied by a 138-page report, that repudiated ex-gay therapy. The report concluded that compelling evidence suggested that cases of individuals going from gay to straight were “rare” and that “many individuals continued to experience same-sex sexual attractions” after reparative therapy. The APA resolution added that “there is insufficient evidence to support the use of psychological interventions to change sexual orientation” and asked “mental health professionals to avoid misrepresenting the efficacy of sexual orientation change efforts by promoting or promising change in sexual orientation.” The resolution also affirmed that same-sex sexual and romantic feelings are normal.

A very large number of professional medical, scientific and counseling organizations in the U.S. and abroad have issued statements regarding the harm that reparative therapy can cause, particularly if it’s based on the assumption that homosexuality is unacceptable. As early as 1993, the American Academy of Pediatrics stated that“[t]herapy directed at specifically changing sexual orientation is contraindicated, since it can provoke guilt and anxiety while having little or no potential for achieving change in orientation.”

The American Medical Association officially opposes reparative therapy that is “based on the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based on an a priori assumption that the person should change his/her homosexual orientation.”

The Pan-American Health Organization, the world’s oldest international public health agency, issued a statement in 2012 that said, in part: “Services that purport to ‘cure’ people with non-heterosexual sexual orientation lack medical justification and represent a serious threat to the health and well-being of affected people.” The statement continues, “In none of its individual manifestations does homosexuality constitute a disorder or an illness, and therefore it requires no cure.”

Some of the most striking, if anecdotal, evidence of the ineffectiveness of sexual reorientation therapy has been the numerous failures of some of its most ardent advocates. For example, the founder of Exodus International, Michael Bussee, left the organization in 1979 with a fellow male ex-gay counselor because the two had fallen in love. Other examples include George Rekers, a former board member of NARTH and formerly a leading scholar of the anti-LGBT Christian right who was revealed to have been involved in a same-sex tryst in 2010. John Paulk, former poster child of the massive ex-gay campaign “Love Won Out” in the late 1990s, is now living as a happy gay man. And Robert Spitzer, a preeminent psychiatrist whose 2001 research that seemed to indicate that some gay people had changed their orientation, repudiated his own study in 2012. The Spitzer study had been widely used by anti-LGBT organizations as “proof” that sexual orientation can change.

In 2013, Exodus International, formerly one of the largest ex-gay ministries in the world, shut down after its director, Alan Chambers, issued an apology to the LGBT community. Chambers, who is married to a woman, has acknowledged that his same-sex attraction has not changed. At a 2012 conference, he said: “The majority of people that I have met, and I would say the majority meaning 99.9% of them, have not experienced a change in their orientation or have gotten to a place where they could say they could never be tempted or are not tempted in some way or experience some level of same-sex attraction.”

Reference

- 10 ANTI-GAY MYTHS DEBUNKED, Southern Pverty Law Center, 27 February 2011, by Evelyn Schlatter and Robert Steinback https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2011/10-anti-gay-myths-debunked