For most of the twentieth century, homosexuals were considered mentally ill by the psychiatric profession. This diagnosis was due entirely to prejudice and was not backed by legitimate science. Studies on homosexuality were poorly conceived, culturally biased and often used institutionalized mental patients as study subjects.

After reviewing the evidence, in 1973 the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), which is its list of mental disorders. There was simply no logical or coherent reason to stigmatize gay and lesbian Americans. Not long after, every respected mainstream medical and mental heath association followed the APA’ lead.

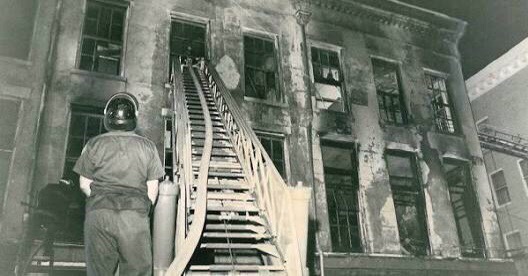

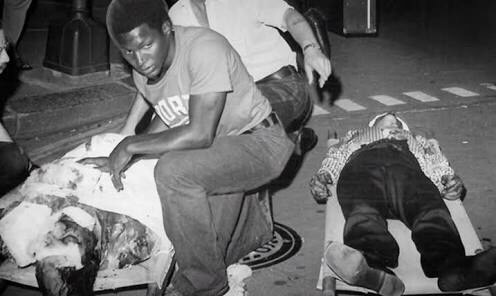

Only four years before this monumental decision, the Stonewall riots in New York City’ Greenwich Village ushered in the dawn of the modern gay liberation movement. For the first time, GLBT people began to receive media visibility and coming out finally seemed like a viable option.

As more people chose to live honestly and openly, and gay communities began to flourish in areas such as New York and San Francisco, this presented a challenge to conservative churches, which had long believed that homosexuality was sinful behavior. Many conservative gay Christians were deeply conflicted between their beliefs and their sexual orientation. Their answer to this heart-wrenching dilemma was starting ex-gay ministries. Influenced by the miracle-seeking Jesus Movement, the ex-gay ministries adopted name and claim theology. Essentially, this meant if you kept repeating you had “changed” — even if you had not — God would eventually grant you the miracle of heterosexuality as a reward for your faith.

Love In Action was the first contemporary ex-gay ministry and was founded in 1973 in San Raphael, CA, by three men: John Evans, Rev. Kent Philpott, and Frank Worthen.

Evans ultimately denounced Love In Action after his best friend Jack McIntyre committed suicide in despair over not being able to “change.” Today, Evans assists people in healing from the psychological damage incurred by the ex-gay industry. Frank Worthen still remains with the ex-gay ministries.

Philpott, who is straight, wrote “The Third Sex? ” which featured six people who supposedly converted to heterosexuality through prayer.

Eventually, it was revealed no one in his book actually had changed, but the people reading it had no idea about the unsuccessful outcomes. As far as they knew, there was a magical place in California that had figured out the secret for making gays into straights.

As a result of Philpott’ book, within three years more than a dozen “ex-gay” ministries spontaneously sprung up across America. Two leading “ex-gay” counselors at Melodyland Christian Center in Anaheim, California – Gary Cooper and Michael Bussee – decided to organize a conference where members of the budding ex-gay movement could meet each other and network.

In September 1976, Cooper and Bussee’ vision came to fruition as sixty-two “ex-gays” journeyed to Melodyland for the world’ first “ex-gay” conference. The outcome of the retreat was the formation of Exodus International, an umbrella organization for “ex-gay” groups worldwide.

The group was rocked to its core a few years later when Bussee and Cooper acknowledged that they had not changed and were in love with each other. They soon divorced their wives, moved in together and held a commitment ceremony. In June 2007, Bussee issued an apology at an Ex-Gay Survivors Conference to all of the people he helped get involved in ex-gay ministries.

The Expansion of the Ex-Gay Industry

In 1979, Seventh Day Adventist minister Colin Cook founded Homosexuals Anonymous (HA). But Cook’ “ex-gay” empire crumbled a few years later after he was scandalized for having phone sex and giving nude massages to those he was supposedly helping become heterosexual.

As acceptance for homosexuality grew in the late 1970′, the “ex-gay” ministries had trouble attracting new recruits and growth of these programs stagnated. With the advent of AIDS, however, the ex-gay ministries found fertile growth potential from gay men who were terrified of contracting the virus.

Nonetheless, even as the epidemic spurred new growth, the “ex-gay” ministries remained relatively obscure in mainstream society. This dramatically changed in 1998 when the politically motivated Religious Right embraced the “ex-gay” ministries. Fifteen anti-gay organizations launched the “Truth In Love” newspaper and television ad campaign, with an estimated one million dollar price tag.

But the ad campaign soon backfired after University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard was murdered because of his sexual orientation. Americans began to see the Truth In Love campaign as discriminatory and debated whether it had contributed to a climate of intolerance where hate could flourish. Due to withering criticism in the media, the anti-gay coalition ended its campaign prematurely.

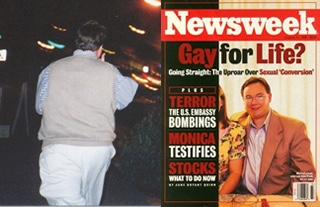

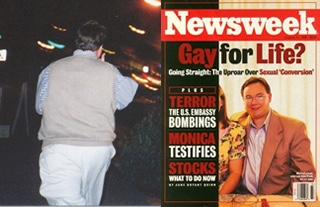

Additionally, “ex-gay” poster boy John Paulk, who the ad campaign sponsors placed on the cover of Newsweek under the large headline, “Gay for Life?,” was photographed in a Washington, DC gay bar in 2000. In 2003, Michael Johnston, the star of the Truth In Love television campaign, stepped down after allegedly having sex with men he met on the Internet. He has since moved to a residential sex addiction facility in Kentucky.

Today, the main financier and facilitator of ex-gay ministries is Focus on the Family, which hosts a quarterly symposium called Love Won Out. Exodus International has also grown to more than 100 ministries and has a Washington lobbyist. Recently, the Southern Baptist Convention has entered the fray by hiring a staff member to oversee ex-gay programs.

Sadly, as long as people are made to feel ashamed for who they are, these groups will exist. The best way to counter their negative influence is showing an honest and accurate portrayal of GLBT life. When people learn that they can live rich and fulfilling lives out of the closet, the appeal of these dangerous and ineffective groups invariably wanes.

The Abominable Legacy of Gay-Conversion Therapy

Joseph Nicolosi, one of the pioneers of the practice, died last week. But his contribution to the field of psychology lives on.

“I don’t believe anyone is really gay,” Joseph Nicolosi told the New York Times in 2012. “I believe that all people are heterosexual, but that some have a homosexual problem.” Nicolosi, a psychologist, had by then written four books, with titles like Healing Homosexuality and A Parents’ Guide to Preventing Homosexuality. In 1992, he founded the National Organization for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality, or NARTH, an organization of psychologists that aims to help gay people “realize their heterosexual potential” through a practice that is alternately known as “conversion therapy,” “reparative therapy,” and “reorientation therapy.” Nicolosi died on Thursday, March 8, at age 70; NARTH’s announcement said that the cause of death was the flu.

Before NARTH’s founding, there was a small but violent history of gay conversion attempts by doctors and psychologists. In the early 20th century, Freud made attempts using hypnosis. In the 1950s, Edmund Berger advocated a “confrontational therapy” approach to gay patients, which consisted of having practitioners yell at them that they were liars and worthless. Other attempts to convert LGBT people to heterosexuality throughout history have included methods like lobotomy, electroshock to the hands, head, and genitals, testicle transplants from dead straight men “bladder washing,” castration, female circumcision, nausea-inducing drugs, and beatings. But it was Nicolosi who brought gay conversion therapy into the mainstream, popularizing it among religious communities and the American right, and turning what was once a scattered practice of abuse into a multi-million-dollar worldwide industry.

Nicolosi grew up in New York; he received a master’s degree from the New School and spoke in a thick Long Island accent. But he spent his career in Los Angeles. He received a PhD in clinical psychology from an obscure school there, and opened his own clinic in Encino in 1980. He seems to have focused his practice entirely on gay conversion attempts. The time was ripe. The social movements of the 1960s and the gay rights activism that flourished after the Stonewall Riots in 1969 ignited profound fear on the American right. Nicolosi found an eager audience for his claim that heterosexuality and traditional gender conformity were not only superior, but that deviations from them were pathological.

What Nicolosi offered was a way for homophobic parents, patients, and psychologists to validate their anti-gay feelings as being legitimated by nature, science, and psychological evidence.

The field of psychology had never been particularly welcoming to queers, but by the time Nicolosi began practicing, attempts to convert gays had already been relegated to quackery. Freud wrote that the prognosis for heterosexual feeling in homosexual patients was grim (though he did believe that gay impulses could be reduced under some circumstances). In 1932, Helene Deutsch published her study “On Female Homosexuality,” which recounted Deutsch’s attempts to instill heterosexuality in a lesbian, only to find that her patient had begun a relationship with another woman while the study was ongoing. In her conclusion, Deutsch noted that a straight relationship would have been her preferred outcome, but also seemed to acknowledge her patient’s lesbian partnership as psychologically healthy.

In 1948, just a year after Nicolosi was born, Alfred Kinsey published his groundbreaking report Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, which found that homosexual tendencies were much, much more common than had previously been assumed. In 1978, the American Psychological Association removed homosexuality from its list of clinical disorders in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Anti-gay stigma and bigotry were still rampant, both within the culture and within the field, but establishment psychologists had given up conversion attempts as a lost cause.

What Nicolosi offered was a way for homophobic parents, patients, and psychologists to validate their anti-gay feelings as being legitimated by nature, science, and psychological evidence. He established NARTH in 1992 alongside Benjamin Kaufman and Charles Socarides, two other obsessively anti-gay psychologists, explicitly in reaction to the removal of homosexuality from the DSM. They spoke in appealingly professional jargon, using phrases like “trauma” and “bad attachment.”

The organization became a network for homophobic psychologists, as well as a link between the industry and the growing number of ex-gay ministries and “pray away the gay” programs on the Christian right. Nominally secular, NARTH and Nicolosi frequently embraced religious rhetoric and prayer tactics, and were listed as ministry partners by a number of homophobic Christian organizations. The Thomas Aquinas Psychological Clinic, where NARTH is headquartered, is named after a Catholic saint. “We, as citizens, need to articulate God’s intent for human sexuality,” Nicolosi told Anderson Cooper in 2007. That same year, he told an ex-gay conference, “When we live our God-given integrity and our human dignity, there is no space for sex with a guy.”

Nicolosi’s treatments often involved multiple one-on-one sessions per week. According to accounts given by former patients, he seems to have used a mix of Berger’s “confrontational therapy” methods of emotional abuse with what’s known as aversion therapy. Aversion therapy applies pain or discomfort to patients in conjunction with homosexual impulses or behaviors: Everything from snapping a rubber band around a patient’s wrist to giving them electric shocks to making them vomit. He believed that gay people had bad relationships with their parents in absolutely all cases, and spent a great deal of therapeutic time probing patients for incidents of humiliation, neglect, or contempt in their childhoods.

In his books, he instructed parents to monitor their children for supposed early signs of queerness, including shyness or “artistic” tendencies in boys.

For unclear reasons, he also believed that viewing pornography could cure homosexuality, an idea he repeatedly defended to professional gatherings. Programs associated with NARTH have been found to administer beatings to their patients. The majority of Nicolosi’s patients, like the majority of conversion therapy victims generally, were children and adolescents, forced into his care by parents who were bigoted, sadistic, or merely scared. Nicolosi encouraged these impulses; he claimed to be able to identify and reverse homosexuality in children as young as three. In his books, he instructed parents to monitor their children for supposed early signs of queerness, including shyness or “artistic” tendencies in boys.

But even before Nicolosi died, NARTH was facing a host of challenges. It lost its nonprofit status in 2012, and an important accreditation from the California Board of Behavioral Sciences was revoked in 2011. Prominent members of the group have been embroiled in controversy, including George Rekers, a conversion therapy psychologist who was discovered to have hired a 20-year-old male sex worker in 2010. California outlawed the practice for minors in 2012, cutting deeply into NARTH’s L.A.-based operations; New Jersey, Illinois, New York, Vermont, and Oregon have since passed their own bans. But the group and its imitators continue to harm both children and adults.

Discovering that you are gay, or that your child is gay, is frightening. It means confronting a future that will not look like the one that you expected, and it means realizing that you and people you love will be subjected to stigma, discrimination, harassment, and the punitive whims of the state. It means staring down a life with fewer certainties and more vulnerabilities than a straight person’s. Scared and misguided people went to Nicolosi for help, and he exploited their fear to perpetuate hate, inflicting horrible pain and incalculable psychological damage on his victims in the process. It is unfortunate that his legacy won’t die with him.

References