The tale of Captain Moonlite

I first learned of Captain Moonlite from the historian Graham Willett. In Secret Histories of Queer Melbourne, a book Willett co-edited, Moonlite features “as the bushranger most likely to qualify as queer”.

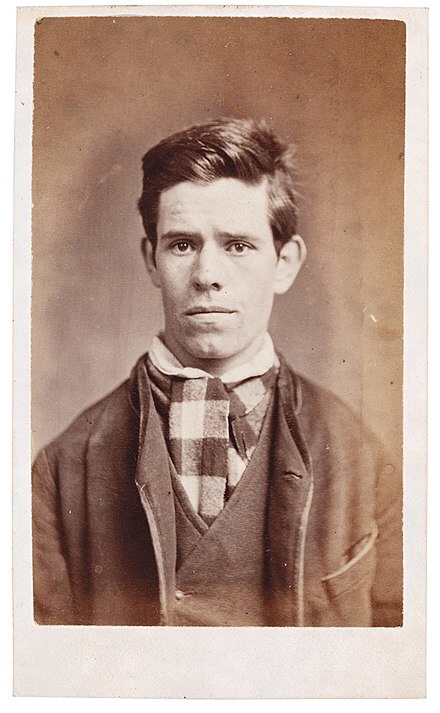

Andrew George Scott – George to his friends – was born in 1845 (some records say 1843) to a wealthy family in Ireland. He emigrated with them to New Zealand in 1861, where his father served as a clergyman and magistrate. Arriving in Australia six years later, the young Scott, too, became a lay preacher, before turning to crime. In 1879, he held up a cattle station in New South Wales. Two of his associates were killed when the police arrived, as was a constable – and Scott was hanged in Sydney at the start of the following year.

But it was Scott’s relationship with James Nesbitt, one of his gang members, that attracted Willett’s attention. “Nesbitt and I were united by every tie which could bind human friendship,” wrote Scott (underlining and all) during his final incarceration. “We were one in hopes, one in heart and souland this unity lasted until he died in my arms.” Awaiting execution, Scott wore a ring made from Nesbitt’s hair, and pleaded with his gaolers to bury him with the younger man in the graveyard at Gundagai.

“I long to join him where there shall be no more parting,” he wrote.

The request wasn’t granted, of course, but Willett’s account concludes by explaining how, in 1995, “a group of [Scott’s] admirers persuaded the government to surrender Moonlite’s body to be re-interred in the Gundagai cemetery”.

That struck me as entirely remarkable. Exhumation requests are seldom granted. Given the context, I’d assumed Moonlite’s “admirers” to be queer agitators. One of them was a woman called Christine Ferguson, who was definitely an activist – but her activism centred on the National Party, of which she’d been federal president until earlier this year.

What was going on? Why had a leader of a staunchly socially conservative party gone to such trouble to re-bury an executed murderer next to the man he loved?

I found the phone number of the cattle and sheep station Ferguson runs near Gundagai. Oh, yes, she said, she’d love to talk about Moonlite.

When Scott landed in Victoria in 1868, he may well have been fleeing a scandal concerning his military service in New Zealand. Regardless, the Bishop of Melbourne offered the well-spoken newcomer a plum post as a lay preacher in the Bacchus Marsh settlement. At the time, worshippers there were still gathering each Sunday in a building known as the Iron Church, one of many pieces of prefabricated infrastructure imported during the Victorian gold rush. In archival photos, it looks like a corrugated-iron shed, unflatteringly supplemented with a steeple.

Such was the colony at the time: a still fluid society in which the stone certainties of Anglicanism were replicated with ersatz materials entirely unsuited to the local climate. The setting suited Scott, who emerges from Paul Terry’s authoritative biography In Search of Captain Moonlite as charming, self-centred, and almost entirely amoral.

The Reverend WH Cooper of Bacchus Marsh presented the recruit to his flock “as a young warrior who now has a firm grip on the sword of righteousness”. And, at first, Scott justified Cooper’s faith. The archivist at Bacchus Marsh’s present-day Holy Trinity Church showed me a weathered ledger where Scott’s beautiful copperplate signature repeatedly appeared alongside the number of parishioners he attracted – generally, close to 100 each week.

But in early 1869 a man called Robert Crook faced the Bacchus Marsh Court House accused of breaking a neighbour’s fences and stealing his cattle. Scott had ingratiated himself with the Crook clan, one of the grandest families in the parish, and obligingly provided the young squire with an alibi. Unfortunately, it was immediately contradicted by one of his Sunday school students, who swore she’d seen Scott and Crook loitering near the crime scene.

Naturally, the court believed a churchman over a teenage girl. But the acquittal did not quell the Anglican hierarchy’s unease about its lay preacher, who was abruptly banished to the isolated mining town of Mount Egerton.

The remains of the Iron Church were sold for scrap in the 1870s to make way for a stone chapel, but the archivist directed me to a decaying house on the corner of Waddell and Graham streets where pieces had been dumped. In the knee-high grass of the backyard I found rusted slabs of iron – remnants of the church – now crudely fashioned into a garden shed. Wasps were nesting on one panel; there was a strong smell of rot coming from inside.

It felt, perhaps fittingly, like a crime scene.

In dusty Mount Egerton, Scott befriended the few respectable people he could find, including a 17-year-old banker, Ludwig Julius Wilhelm Bruun, and the town’s schoolteacher, James Simpson.

On 8 May 1869, Bruun told authorities that a masked man had forced him to open the bank’s safe and hand over its gold. The intruder left a note: “I hereby certify that LW Bruun has done everything within his power to withstand this intrusion and the taking of money which was done with firearms.”

It was signed “Captain Moonlite”.

The whole implausible story was probably a fabrication, a scam cooked up by Scott, Bruun and Simpson. Their friendship, however, had soured, and Bruun said he recognised the gunman as his former friend, tying Scott to the Moonlite moniker. Scott hotly denied the charge and threw the blame back at Bruun and Simpson, who were sent to trial (and later acquitted); Scott departed hurriedly, taking himself to Fiji and then to Sydney, where he began spending the wealth he’d mysteriously acquired.

In late 1870, he was arrested for passing bad cheques. Confined in Maitland Gaol, he feigned madness and was transferred to the more comfortable Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, where the medical registry described him as a “civil but … unprincipled fellow without a spark of honour or decency to him”.

Upon his release in 1872, Scott was charged with the Mount Egerton robbery. While on remand, he dug through the brickwork in his cell and scaled the walls of the gaol. He was quickly recaptured. Redmond Barry (the judge who later sentenced Ned Kelly to death) sentenced Scott to ten years in Melbourne’s Pentridge prison for the robbery, adding one for his attempted escape.

As a criminal, Scott was always more urban hustler than highwayman. But he was handsome and athletic, had reportedly seen heavy combat in the so-called Maori Wars, and was a skilled rider and crack shot. The Captain Moonlite sobriquet, with its irresistible hint of midnight romance, took on a life of its own. His attempted escape further popularised the reputation of the bold and dashing Moonlite. “Brave to the verge of recklessness,” a journalist wrote, “cool, clear-headed and sagacious, and with a certain chivalrous dash, he is the beau ideal of a brigand chief.”

The press thought him a bushranger – and a bushranger he would become.

It was a long drive from Bacchus Marsh to Gundagai. The spring rain had left the wheatfields a deep green and those of canola garishly yellow. The landscape tramped by George Scott and James Nesbitt and their four young companions, in drought-stricken 1879, must have been very different.

Scott met Nesbitt – a petty criminal from Carlton – in Pentridge, where the younger man was once disciplined for “taking tea to Prisoner Scott”. As biographer Terry says, it’s an affectingly tender infraction.

Upon Scott’s release in March 1879, the men shared a rundown house in Fitzroy. But how would they live? Scott tried lecturing on prison reform but, though he drew huge crowds, theatres often refused to book him, particularly with the press linking the notorious Moonlite with every unsolved crime. Police warned potential employers against him; he was dragged in for questioning about the most preposterous allegations.

Scott resolved to walk to New South Wales in search of work and a new start. He took with him a coterie of young men from the slums of inner Melbourne. Like Nesbitt, Thomas Rogan was 21. Frank Johns, Graham Bennett and Augustus Wernicke were in their teens. Exiled from polite society, the 34-year-old Scott basked in the admiration of these youths, to whom, as an urbane intellectual, he seemed like a visitor from another world.

The journey proved an utter disaster, a weary trudge along a hot and inhospitable track. The privations were exacerbated by constant police harassment.

“As long as our money lasted,” Scott explained later, “we bought bread, and when our money was gone we sold our clothes and bought bread, with what we obtained for them. We tried to get work, but could not, and we fasted day after day.”

They’d been living on damper and tea and koala meat – and then no food at all – when they approached Wantabadgery Station, near Gundagai. The property was known for its hospitality but, unbeknown to Scott, it had recently changed hands and the new owner harboured little sympathy for itinerants.

Abruptly ordered to leave, Scott snapped.

“Misery and hunger produced despair,” he wrote later, “and in one wild hour we proved how much the wretched dare.” He retreated into the bush and then returned with gun in hand – transforming, at last, into the persona that had been created for him.

The men with Scott had never previously left the city, let alone ridden a horse. Suddenly, though, they too were bushrangers.

Scott acquired nothing of value at the station. Instead, he demanded food and drink. Leaving his men, he then bailed up the Australian Arms Hotel and detained everyone inside before forcing them back to Wantabadgery: he was more concerned about playing the gentlemanly host than planning an escape.

Inevitably, the police arrived; inevitably, a gunfight ensued.

Scott and his small gang then decamped to a nearby farmhouse, which was soon surrounded by troopers. “Come and fight!” Scott yelled, even though the rest of his gang could barely hold a rifle. Poor Tom Rogan spent the whole shootout hiding under a bed.

Wernicke was mortally wounded. “I am only fifteen,” he cried. A short time later, Nesbitt was shot in the head. A journalist of the time described how, as Nesbitt died, Scott “wept over him like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately”.

In the exchange of fire, Senior Constable Edward Webb-Bowen took a bullet in the spine – his subsequent death sealed Scott’s fate. The surviving “bushrangers” were tried for murder. With the Kelly Gang still at large, the court set an example, handing down death sentences to all. Johns and Bennett received an eventual commutation on the grounds of their youth; Scott and Rogan (who hadn’t even fired a shot) walked to the gallows on 20 January 1880 and were buried at Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery.

I drove to Kimo Estate, about 20 minutes from Gundagai, where a troop of dogs romped up to greet me. A minute later, Christine Ferguson roared into view on a ride-on mower. She was wearing a pullover emblazoned with a Captain Moonlite logo.

“G’day,” she said, wiping clean her hands. “You find the place all right?”

Kimo’s house dates back to the 1870s, and is pleasantly weathered. In spite of recent renovations for the bed-and-breakfast trade, Kimo is still a working farm. We sat in a lounge room crowded with books and framed photos, and talked about the exhumation in 1995.

Ferguson confirmed that disinterring a corpse wasn’t easy.

“We were actually the first people who weren’t relatives or the state to get a body exhumed. The only reason it was possible was because of Moonlite’s last letter, in which he wished to be buried in Gundagai next to his friends.”

But why had Ferguson gone to such trouble? “Here you are putting money and time into re-burying a convicted murderer who seems to have been involved in a same-sex relationship. It does seem, well, a bit strange.”

“Well, it was really only after the whole event that people raised that he might be gay,” Ferguson explained. “For a long time, we said, ‘Look, we believe they were just good mates, good friends.’ Just recently Sam Asimus, my partner in crime in the whole affair, told me she’d done some more research and she thinks Scott might have been bisexual. But who knows?”

As well as exhumation approval from the state, the women needed permission from the Anglican Church – eventually, both were granted. Ferguson’s team enlisted a local undertaker (“He was terribly excited!”), and they brought an ornate horse-drawn hearse to Gundagai on the back roads. The pallbearers wore period costumes.

“The locals here aren’t terribly excited about anything much,” Ferguson said, shrugging. “But when it was all done and it didn’t cost them any money, they did get into the swing of things. We had people lining the roads to watch.”

I still wanted to talk about sexuality. I’d learned about Moonlite from Willett and other gay historians, I explained. “Here was someone saying in those last letters, ‘I love this man, I want to be buried with him.’”

“He actually didn’t say that,” Ferguson said, then corrected herself. “Well, he did say it – in a way. But it was a long time ago, and mates were mates. We don’t know if he was gay or not. It comes down to your interpretation of ‘mate’ and what ‘mateship’ would have meant at the time.”

Fair enough. But mateship was a lot queerer than most people thought. In his 1958 book The Australian Legend, which popularised the concept as a national trait, Russel Ward suggested that, in the masculine environment of the frontier, the typical bushman satisfied himself sexually with prostitutes and indigenous women, then assuaged his “spiritual hunger” with “a sublimated homosexual relationship with a mate, or a number of mates”.

Was that how to think about Scott? In Bacchus Marsh, he seems to have been involved with a woman named Mrs Ames, who felt strongly enough about Scott to visit him regularly before his execution. Yet she barely registers in Scott’s death-cell writings, in which he returns again and again to Nesbitt.

“He died in my arms,” Scott wrote. “His death has broken my heart.”

That didn’t seem sublimated.

In one of his letters, Scott ended his plea for burial alongside Nesbitt with a quotation:

Now call me hence by thy side to be:

The world thou leavest has no place for me.

Give me my home on thy noble heart,

Well have we loved – let us both depart.

The lines came from a Felicia Hemans poem entitled ‘The Lady of Provence’.

“The original was about the feelings of a woman for her dead lover,” I mentioned to Ferguson. “So here’s Scott including what seems to me clearly a love poem to a man.”

“Well, that was never brought up at the time,” she said. “But, again, we don’t have the evidence. Do homosexuals now write poems to each other? It’s an odd thing to do, writing poems – not something people do these days.”

Until quite recently, I’d been the editor of Overland, a literary journal that regularly publishes poetry. Nevertheless, I took the point. The more I read about sexuality in the 19th century, the more it seemed both strikingly familiar and disconcertingly strange.

During Scott’s criminal career, the police in Victoria had been led by Chief Commissioner Frederick Standish. He was a gambler and libertine, who, at one notorious dinner, decorated the room with naked women seated on black chairs to better show off their white bodies. When Prince Alfred, the second son of Queen Victoria, toured Melbourne in 1867, Standish acted as royal pimp, escorting the prince to Sarah Fraser’s brothel in Stephen Street.

But, as Willett says in Secret Histories of Queer Melbourne, the commissioner was also infatuated with men – in particular with Frank Hare, another policeman chasing the Kellys. “It was almost pathetic to see …” wrote one of their contemporaries, “how restless and uneasy [Standish] became were Hare out of his company. I have seen Standish on the top rail of a fence watching anxiously for Hare’s return from a short ride.”

And then there was the story of Edward Feeney, who, eight years before Scott’s execution, was put to death at Melbourne Gaol for his part in a bizarre suicide pact.

In March 1872, Feeney had accompanied Charles Marks into Melbourne’s Treasury Gardens, where, according to a pre-arranged plan, they attempted to shoot each other. Feeney’s gun fired; Marks’ didn’t. This left Feeney on trial for murder.

Feeney refused to offer any explanation. But the court heard that he and Marks exchanged letters about their passionate love for each other. A bar owner testified that they regularly cuddled in his premises, sometimes laying their heads on each other’s laps. In her article about the case, historian Amanda Kaladelfos points out that while the proprietor believed their behaviour unusual, “he expressed no malice toward Marks and Feeney; nor did he give evidence that he ever asked them to stop showing their affections in his place of business”.

“Men often slept together in the same beds,” historian Clive Moore explains in his study of sexuality on the frontier, “without raising the slightest suspicion that they were involved in what we would call a homosexual affair, were physically affectionate, had romantic crushes, wrote lovingly to each other and fretted when they were apart … For most of the 19th century there was no clear social, medical or legal concept of homosexuality; homosexual acts were recognised, particularly sodomy, but not a personal disposition or social identity.”

Today, of course, matters are very different.

“Is there a gay community in Gundagai?” I asked Christine Ferguson.

“Hmm. I know one who’s come here, used to be with Qantas and he’s here … I’ve only met him once but I know he’s here. A couple of others in town who are probably bachelors but most people say they are [gay]. But that’s about it.”

“Do they have a hard time?”

“No, I don’t think so. You really wouldn’t know. They’re not openly living with a bloke or anything. Gundagai is conservative but I don’t think it’s really bothered by homosexuality.”

“Would the town be open to the tourist potential of Moonlite as a gay icon?”

“No, I didn’t think Gundagai would be into that,” Ferguson replied. “A lot of the old people want to keep Gundagai how it is and how it has been in the past. They don’t see … they’re not very progressive.”

She told me that she and Samantha Asimus had wanted to establish a bushrangers and police museum in the old gaol, when a property there became available. They’d had plans for holograms; they’d spoken to the Justice & Police Museum in Sydney about borrowing exhibits.

“We thought it would be fabulous for the town. But no, no one was interested.”

We talked for a little while about politics in general – Ferguson is close friends with Tony Abbott and struggled to sound enthusiastic about Malcolm Turnbull – and then she showed me through the station.

“I like to have a project,” she said. “I like to keep myself busy.”

And that, it seemed, helped to explain her involvement in the re-burial, a cause she’d taken on almost because of its inherent difficulty.

In his cell, Scott had described the headstone he wanted:

[A] rough unhewn rock would be most fit, one that skilled hands could have made into something better. It will be like those it marks, as kindness and charity could have shaped us to better ends.

The words were now carved into a suitably craggy stone located at the very edge of the North Gundagai Cemetery.

In some ways, the sentiment seemed less apposite for Scott (who, in his early life at least, had scarcely been deprived of opportunities) than for the slum kids who died with him.

Ever since I stumbled upon Edward Feeney and Charles Marks’ story, I’d been thinking about the inner-city origins of Moonlite’s unhappy gang, and the strange visual connection between the past and present. Before Marks and Feeney went to the Treasury Gardens to kill each other, they’d posed for final portraits in a Bourke Street photographer’s studio. The resulting images are utterly compelling. In one picture, they’re holding hands – and, with their bushy whiskers and cloth trousers, they look disconcertingly contemporary. You would not blink an eye to see them strolling in Fitzroy or Carlton today.

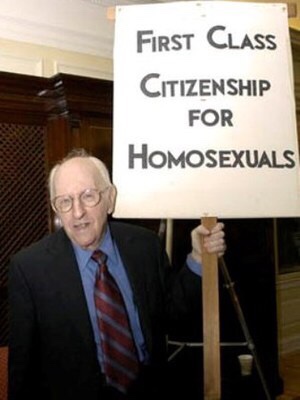

On the scaffold, Feeney had issued a statement denying he’d been “improperly intimate” with Marks. The doctors who dissected his body inspected his rectum for signs of sodomy. In that posthumous indignity, we can detect, Amanda Kaladelfos says, the beginning of the modern science of sexuality, which in the decades to come would establish “homosexuality” as a distinct and all-consuming pathology.

A second photo of Marks and Feeney depicts them with pistols against each other’s breast. The photographer had suggested they pose as “bushrangers”, a comment that made me wonder if, by the 1870s, the life of the outlaw gang was seen as representing a kind of male intimacy that the cities were beginning to exclude.

Was Feeney gay? Was Moonlite? In one sense, asking such questions is almost silly, the projection of contemporary categories onto a past where they did not belong. Yet, in another sense, the rediscovery of men who loved other men (as both Feeney and Moonlite clearly did) matters a great deal.

I’d also asked Christine Ferguson whether, in today’s Gundagai, men who wrote love poems to other men would be welcome in the local pub.

“Yeah, they probably wouldn’t go to the pub,” she replied, amused at the thought. “The pubs in here are pretty blokey.” She didn’t drink in them much herself, and nor did many women.

Surely that was the value of the Moonlite story. It revealed the traditional masculinity enforced in public bars, sporting clubs and other bastions of heterosexuality to be neither innate nor eternal.

Scott had designed his own epitaph. He’d wanted it to read “This stone covers the remains of two friends”. He’d then written Nesbitt’s name and his own, with Nesbitt’s death listed as the date the pair were “separated”, and his own execution recorded as when they were “united by death”.

The exact location of Nesbitt’s body in this cemetery is no longer known. When Scott’s body was re-buried, the tombstone noted that he had been “laid to final rest near his friends James Nesbitt and Augustus Wernicke who lie in unmarked graves close by”.

The inscription diffused Scott’s passion for one man into a more conventional friendship with two.

The morning was starting to warm, but Scott’s grave was pleasantly shaded by a beautiful old gum tree. Its slight separation from the rest of the cemetery gave it an unmistakeable prominence – a gesture that the always-vain Scott would have liked.

Why bushranger Captain Moonlite died with a lock of hair in his hand

HISTORY

Moonlite: The True and Tragic Love Story of Captain Moonlite and the Dying Days of the Bushrangers

Garry Linnell

Michael Joseph, $34.99

In the annals of bushranging, Andrew George Scott (aka Captain Moonlite) is not as familiar a name as Ned Kelly, though arguably he was just as complex and interesting a character as well as being similarly accomplished as a horseman. Scott was Irish – technically more so than Kelly, having been born there – but he came from a very different background from the leader of the Kelly Gang, being well-educated and Protestant. But both had occasion to be tried in a courtroom presided over by Sir Redmond Barry, also an Irishman.

The story of the life and misadventures of Captain Moonlite is recounted with gusto in this book.

The front cover boldly announces “A New Era of Australian Storytelling”, with Garry Linnell explaining that he tried to write a work of non-fiction “in a style that borrows heavily from novels and movies – using character development, pacing, dialogue and sub-plots” to enliven material drawn exclusively from archival sources.

Linnell consciously departs from the conventions of popular history by declaring “I despise footnotes” and questioning whether anyone ever reads them.

The armour notwithstanding, Kelly was not as showy as Scott, who created the legend of Captain Moonlite, dressing himself in a black crepe mask and cape-like coat as though he was a stage villain in some provincial melodrama.

For all its theatricality, the criminal persona was somewhat effective in obscuring Scott’s true identity. The performance was designed to instil fear and awe in Moonlite’s victims though it did have an absurd aspect, since Scott had a limp that tended to give him away no matter how impressively he tried to present himself to the world as a swashbuckling land pirate.

These days Kelly is regarded by many Australians as a prototypical bogan who, if he had been born a century or more later, would have worn flannelette and performed burnouts in a stolen Commodore. By contrast, Captain Moonlite was the nearest thing to a dandy highwayman in the tough yet surprisingly sentimental frontier culture that produced the bushrangers and their networks of supporters. We can imagine Kelly enjoying AC/DC while Scott might have preferred to listen to Adam and the Ants.

Like so many of the misfits and ne’er-do-wells from privileged families in Britain and Ireland that fetched up in far-flung colonies, Scott tried different careers but could not settle down to anything respectable. Linnell speculates that Scott, who pleaded insanity at a trial for fraud and was confined to the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum, was bipolar. The authorities concluded that Scott was feigning mental illness while plotting to escape and had him transferred to a regular prison.

Like Kelly, Scott’s career as a bushranger was curtailed in part by the then new modern technology of the telegraph and the railway, as well as more effective policing.

Perhaps the most compelling section of Moonlite features the extraordinary tenderness with which Scott regarded his last partner in crime and the love of his life, James Nesbitt, whom he met while both men were doing time in Pentridge. Scott was disarmingly frank about his feelings for the younger man, especially in an era during the 19th century when sex was not discussed publicly and homosexuality was harshly suppressed by the state.

Scott was captured following a deadly shootout and condemned to be executed. Linnell writes that at the end of his troubled life he thought only of Nesbitt, who had died in his arms during the last stand of Captain Moonlite.

“When they finally hauled Scott to his feet, handcuffed him and led him away, Scott took with him a lock of Nesbitt’s hair. In the years to come, as legend and myth and fact all merged into one, it would be said that Captain Moonlite went to the gallows with that lock of hair forming a ring on the wedding finger of his left hand.”

Reference

- A queer bushranger, The Monthly, November 2015, by Jeff Sparrow

- Why bushranger Captain Moonlite died with a lock of hair in his hand, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 December 2020, by Simon Caterson https://www.smh.com.au/culture/books/why-bushranger-captain-moonlite-died-with-a-lock-of-hair-in-his-hand-20201204-p56knq.html