1979: Banned powders still on sale in Sydney

First published in the Sydney Morning Herald on September 5, 1979

Compound painkillers which were banned from sale from July 1 are still freely sold across the counter in Sydney.

Chemists as well as other retailers were found breaking the law yesterday.

The banned compounds have a mixture of two or more of the substances aspirin, paracetamol, salicylamide and caffeine.

In place of the compound analgesics, drug manufacturers are distributing for open sale single analgesics in similar packets.

But yesterday I bought compound analgesics at four of 14 city shops without difficulty.

At a cafe in George Street, Vincent’s powders made of aspirin, caffeine, citrate and salicylamide were in a plastic cup behind the counter. I was told I could buy only one sachet.

Another George Street cafe kept compound Vincent’s powders on view. Two assistants asked how many I would like.

Two of 10 pharmacies sold me compound analgesics.

A pharmacy in Liverpool Street displayed the new, single-analgesic Bex, but a white-coated man needed no prompting to offer for sale a box of compound-formula Bex. He said it was his last.

He collected the Bex from a back room and said he had been trying to “sell all the old stock” because of the new restrictions.

When I asked for a packet of Bex powders at a George Street pharmacy the sales assistant said only the new formula Bex was in stock, but would I like some of the old kind of Vincent’s?

When I answered yes, the assistant spoke to a whitecoated man. This man asked how many powders I wanted, collected a box of 24 from a back room, handed them over surreptitiously and whispered the price.

Peter Kennedy, State Political Correspondent, was able to buy a four-sachet-pack of Vincent’s compound powders in Macquarie Street yesterday. He writes:

The regulations on compound analgesics were tightened because substantial evidence of a direct link between overuse of the analgesics and kidney failure.

Retailers who illegally sell them face a maximum penalty of an $800 fine or six months jail.

The executive Officer of the NSW Drug and Alcohol Authority, Mr Brian Stewart, said that retailers of the compound analgesics were clearly breaking the law.

“Ample warning has been given,” he said. “It means the retailers are liable to the stiff penalties and are acting contrary to the interests of public health.”

Bitter pills: a quick fix, and a long road to recovery

The silent generation – those who came before the baby boomers – were a stoic bunch who resisted taking drugs to treat even the worst ailments. Migraines, muscle pain and insomnia were treated through a cup of tea, a warm bath, a lie down or fresh air.

But with the 1960s, a new, medical element was added to that mix when a marketing phrase entered the vernacular: ”Have a cup of tea, a Bex and a good lie down.”

Bex, the analgesic made up of aspirin, phenacetin and caffeine, became an Australian icon. It was recommended to treat headaches, colds, flu, fevers, rheumatism, nerve pain and for ”calming down”.

Dissolving some Bex powder in a cup of tea became particularly common among housewives, widely available and sometimes taken up to three times a day.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that clinicians realised Bex and other similar formulations were responsible for kidney disease and addiction, and was carcinogenic. Phenacetin was pulled from the market by 1983.

But the damage had been done, says the director of the National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction at Adelaide’s Flinders University.

Professor Ann Roche says taking drugs for even mild illness or stress became a ”common Australian tradition” and has remained so.

Aggressive marketing from drug companies meant it was even common to pop an analgesic in children’s lunch boxes. ”Generally we don’t think twice about taking certain medications,” Professor Roche says.

‘We see it as fairly common and benign and something that has been used for decades and there is now this tradition of using drugs for pain relief, sleeping issues or anxiety.”

But this attitude has now extended to stronger, prescription drugs being commonly requested from doctors as a first line of treatment.

The 2013 Global Drug Survey found almost half of all respondents had used prescription drugs in the past year, with up to 10 per cent experiencing signs of dependency. Of 2700 prescription drug users, 12 per cent said they had shared them, while 12 per cent mixed them with alcohol to enhance the effects. People also reported using the drugs, particularly opiates, to induce positive emotional and behavioural states.

Opiates, such as oxycodone, continue to be prescribed for chronic pain, even though scientists have shown in recent years they may not be very effective for long-term use. While they are effective for cancer pain and short-term pain, many doctors and patients have failed to realise there are better first-line treatments.

Benzodiazepines, such as Xanax, Serepax and Valium, are being used for short-term stress and anxiety.

”But the big shift we’ve seen in the last few years is towards oxycodone and the other one is fentanyl, mistakenly seen as innocuous as it enters the blood through a skin patch,” Professor Roche says.

Not only are people using them but they are sharing drugs including sleeping pills and pain relievers with family and friends.

There is no ”typical” drug abuser, Professor Roche says, with varying groups trying to get hold of the drugs. Professionals are using them to cope with the stresses of life, while illicit drug users are turning to prescription drugs as cheaper, easier-to-obtain and perceived ”safer” options.

More people are surviving severe trauma, Professor Roche says, such as car accidents or disabilities, often requiring long-term medication and opening the potential for addiction. People are getting older and fatter and suffering from joint pain, she says, overwhelming doctors who sometimes prescribe drugs as a first-line treatment. ”Another contributing factor to growing use is shortened hospital stays thanks to keyhole surgery and other medical advances,” she says.

”This facilitates a faster discharge, where patients are often given quite a lot of pain medication with repeat scripts that people just keep filling even if they no longer really need them.”

A former prescription drug abuser, Charlotte*, would use anxiety drugs every day, taking up to 35 Valium mixed with 10 to 12 Xanax. They were sometimes mixed with heroin.

That kind of intake saw her overdose and come close to death three times. Because of her schizophrenia, she could tolerate higher doses of the drugs, combined with the fact she had built up a tolerance to prescriptions from the age of 14.

About 20 of her friends have died, either through prescription overdose or from illicit drugs combined with prescription medication. She is 23.

”I started on prescription drugs at about 13 and I guess they were my gateway drug into illicit substances,” she says. ”Xanax was my main problem, followed with Valium and Serapax and then I went on to heroin and ice.

”I used to get it from friends and then I started doctor shopping.”

At 17, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia. And while her psychiatrist refused to prescribe benzodiazepines, Charlotte says it was much easier to use her diagnosis to get the drugs from general practitioners.

She went back to the same doctors again and again.

”My friends and I had a list and all the drug users would see the same people,” she says. ”And they knew we were abusing them. Unless they were really stupid, they knew.”

She has been clean for 14 months, but says weaning off the prescription drugs was harder than stopping heroin.

She went to a rehabilitation clinic in Thailand, taking three months to get off the pills.

”I have seen heaps of bad things from prescription drugs; I think they’re worse than heroin,” she says. ”You’d think meth and heroin would be the worst but the thing is every time my friends or I overdosed on heroin, its always because [it was] mixed with drugs like Xanax and Valium.”

While she acknowledges she was an extreme user, Charlotte says people in general are too often turning to prescription drugs for minor ailments. She would like to see Valium banned.

Alex Wodak was the director of the alcohol and drug service at Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital until last July, a position he held for more than 30 years. He has seen first-hand the shift towards people seeking fast comfort.

”People work seven days a week and are always available because of computers and phones, working around the clock,” he says.

”Family life is sacrificed and I think we’re paying the price.

”We have to look at what kind of community we want and we need politicians to implement family-oriented policies.

”We are living in an era where a lot of people are seeking comfort and solace from chemicals; it is a trend that is very supported in our culture.”

Dr Wodak is now working in the area of drug reform. He believes tackling prescription drug abuse is achievable.

”If we stay calm and base policy on evidence I believe we can come out of this,” he says. ”What’s so difficult is the power of the pharmaceutical industry.

”But what we have seen in the cases of tobacco and increasingly with alcohol is that community resentment about a lack of action to fix the problem builds and sooner or later, they will vote for a politician willing to take a stand.”

*Not her real name.

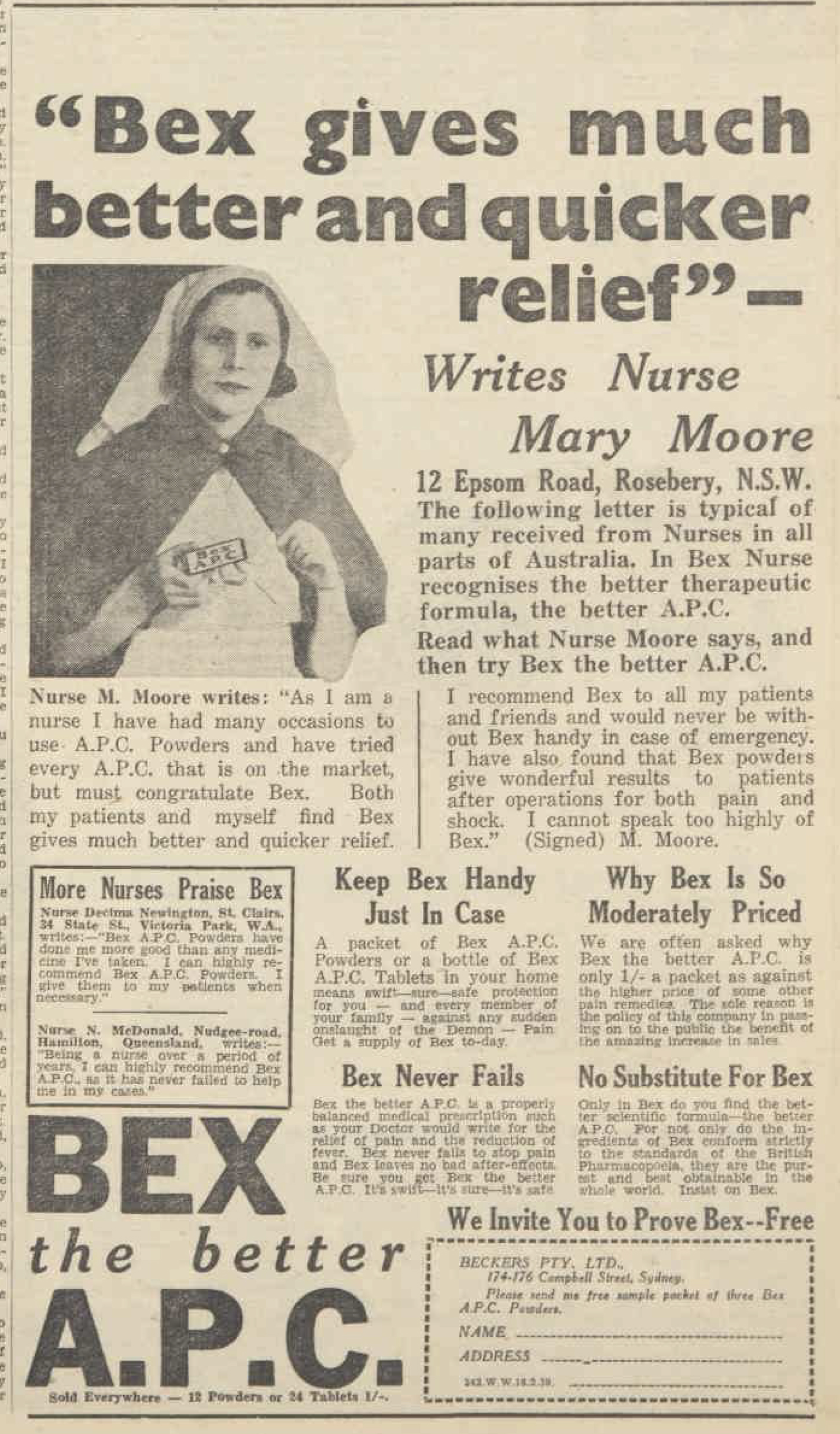

Bex Powders

Bex Powders were a compound analgesic that comprised aspirin (420mg), phenacetin (420 mg) and caffeine (160mg), also known as APC. It was the first APC product marketed in Australia and the most popular. Bex Powders were produced from the 1920s in South Australia by Beckers Pty Ltd. [1] Beckers moved to Sydney in the 1960s and in 1964 was based at the corner of Campbell and Crown Streets, Sydney. [2] Bex Powders were commonly taken by dissolving the powder in water or a cup of tea. The packaging claimed a Bex would relieve ‘Headache, Neuralgia, Rheumatism, Sciatica, Lumbago…Influenza and Cold in early stages’. [3]

Cultural references

Bex were promoted particularly to women with the advertising slogan ‘Stressful day? What you need is a cup of tea, a Bex and a good lie down’. [4] The line has become part of the Australian vernacular and can be used to suggest that someone should relax and ease up. The Bex slogan was immortalised in 1965 when the Phillip Street Theatrestaged a long-running satirical review A Cup of Tea, a Bex and a Good Lie Down, written by John McKellar and starring Reg Livermore and Ruth Cracknell. Over forty years later, in September 2011, Kevin Rudd, addressing suggestions he might challenge the incumbent Prime Minister Julia Gillard, told journalists ‘I just think it would be a good thing if everyone seriously had a cup of tea and a Bex and a long lie down, OK?’ [5]

The problem with Bex

The recommended daily dose of caffeine is 250mg per day and yet Bex packaging advised taking at least two powders, containing 320mg of caffeine. It has been recorded that many women took up to 30-40 doses a day, sometimes washed down with Coca-Cola, adding to the caffeine intake and strengthening the addiction. A further complication was that many of these women were also prescribed Valium, another addictive substance.

In the 1960s Dr. Priscilla Kincaid-Smith discovered that Bex Powders were addictive and that the large doses of phenacetin consumed by habitual users caused kidney disease.

One woman, Norma O’Hara took Bex Powders sometimes twice a day every day for up to eight years from when she was 20. She used to work at Rosebery Wrigley’s factory and said ‘most of the girls took Bex… it was to keep you going. Working the machines, you thought you needed them.’ [6] O’Hara was subsequently diagnosed with kidney failure which was linked to compound analgesic abuse. It was common practice for factory managers to provide Bex Powders free of charge to their workers.

APC compounds were banned in 1977 and painkillers containing them were removed from the Australian market. Over time, this led to a dramatic decline in kidney disease. [7]

Reference

- From the Archives, 1979: Banned powders still on sale in Sydney, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 September 1979, by Deborah Hope https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/from-the-archives-1979-banned-powders-still-on-sale-in-sydney-20190829-p52lx5.html

- Bitter pills: a quick fix, and a long road to recovery, Sydney Morning Herald, 17bMarch 2013, by Melissa Davey https://www.smh.com.au/national/bitter-pills-a-quick-fix-and-a-long-road-to-recovery-20130316-2g7mw.html

- BEX Powders, Dictionary Of Sydney, 2016, by Kim Hanna https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/bex_powders

In 1992, the

In 1992, the

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/angkor-wat-buddha-56a0c4e35f9b58eba4b3a93c.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Gandhara_Buddha_-tnm-56a0c4e15f9b58eba4b3a927.jpeg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Buddha_Victoria_-_Albert-56a0c4df3df78cafdaa4db12.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Fasting_buddha_at_lahore_museum-56a0c4e45f9b58eba4b3a945.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Ayutthaya-Buddha-Head-56a0c4db5f9b58eba4b3a905.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Ayutthaya-Buddha-Head-closer-56a0c4e55f9b58eba4b3a94d.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/longmen-vairocana-56a0c4d93df78cafdaa4dafa.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/vairocana-2-56a0c4e25f9b58eba4b3a930.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Leshan-Buddha-56a0c4dd5f9b58eba4b3a911.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Gal-Vihara-Sitting-Buddha-56a0c4e75f9b58eba4b3a95f.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/kamakura-56a0c4dc3df78cafdaa4db08.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/TianTanBuddha-56a0c43e5f9b58eba4b3a309.jpg)