The Nyingma school, also called Nyingmapa, is the oldest of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. It was established in Tibet during the reign of the Emperor Trisong Detsen (742-797 CE), who brought the tantric masters Shantarakshita and Padmasambhava to Tibet to teach and to found the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet.

Buddhism had been introduced to Tibet in 641 CE, when the Chinese Princess Wen Cheng became the bride of the Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo. The princess brought with her a statue of the Buddha, the first in Tibet, which today is enshrined in the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. But the people of Tibet resisted Buddhism and preferred their indigenous religion, Bon.

According to Tibetan Buddhist mythology, that changed when Padmasambhava called forth the indigenous gods of Tibet and converted them to Buddhism. The fearsome gods agreed to become dharmapalas, or dharma protectors. From then on, Buddhism has been the principal religion of the Tibetan people.

The construction of Samye Gompa, or Samye Monastery, probably was completed about 779 CE. Here Tibetan Nyingmapa was established, although Nyingmapa also traces its origins to earlier masters in India and in Uddiyana, now the Swat Valley of Pakistan.

Padmasambhava is said to have had twenty-five disciples, and from them a vast and complex system of transmission lineages developed.

Nyingmapa was the only school of Tibetan Buddhism that never aspired to political power in Tibet. Indeed, it was uniquely disorganized, with no head overseeing the school until modern times.

Over time, six “mother” monasteries were built in Tibet and dedicated to Nyingmapa practice. These were Kathok Monastery, Thupten Dorje Drak Monastery, Ugyen Mindrolling Monastery, Palyul Namgyal Jangchup Ling Monastery, Dzogchen Ugyen Samten Chooling Monastery, and Zhechen Tenyi Dhargye Ling Monastery. From these, many satellite monasteries were built in Tibet, Bhutan and Nepal.

Dzogchen

Nyingmapa classifies all Buddhist teachings into nine yanas, or vehicles. Dzogchen, or “great perfection,” is the highest yana and the central teaching of the Nyingma school.

According to Dzogchen teaching, the essence of all beings is a pure awareness. This purity (ka dog) correlates to the Mahayana doctrine of sunyata. Ka dog combined with natural formation—lhun sgrub, which corresponds to dependent origination—brings about rigpa, awakened awareness. The path of Dzogchen cultivates rigpa through meditation so that rigpa flows through our actions in everyday life.

Dzogchen is an esoteric path, and authentic practice must be learned from a Dzogchen master. It is a Vajrayana tradition, meaning that it combines use of symbols, ritual, and tantric practices to enable the flow of rigpa.

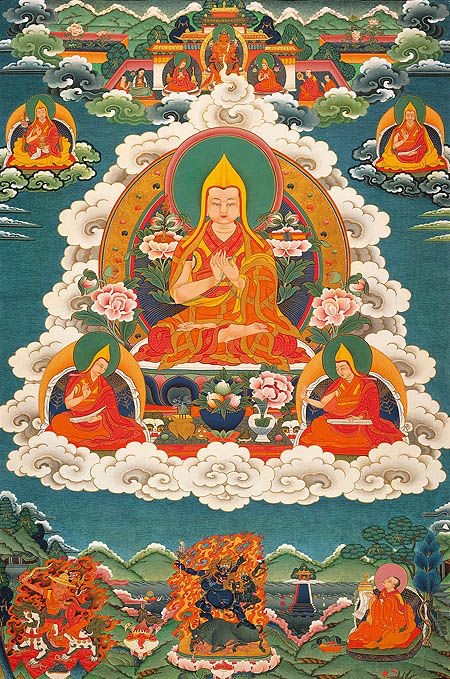

Dzogchen is not exclusive to Nyingmapa. There is a living Bon tradition that incorporates Dzogchen and claims it as its own. Dzogchen is sometimes practiced by followers of other Tibetan schools. The Fifth Dalai Lama, of the Gelug school, is known to have been devoted to Dzogchen practice, for example.

Nyingma Scriptures: Sutra, Tantra, Terma

In addition to the sutras and other teachings common to all schools of Tibetan Buddhism, Nyingmapa follows a collection of tantras called the Nyingma Gyubum. In this usage, tantra refers to teachings and writings devoted to Vajrayana practice.

Nyingmapa also has a collection of revealed teachings called terma. Authorship of the terma is attributed to Padmasambhava and his consort Yeshe Tsogyal. The terma were hidden as they were written because people were not yet ready to receive their teachings. They are discovered at the appropriate time by realized masters called tertons, or treasure revealers.

Many of the terma discovered so far have been collected in a multi-volume work called the Rinchen Terdzo. The most widely known terma is the Bardo Thodol, commonly called the “Tibetan Book of the Dead.”

Unique Lineage Traditions

One unique aspect of Nyingmapa is the “white sangha,” ordained masters and practitioners who are not celibate. Those who live a more traditionally monastic, and celibate, life are said to be in the “red sangha.”

One Nyingmapa tradition, the Mindrolling lineage, has supported a tradition of women masters, called the Jetsunma lineage. The Jetsunmas have been daughters of Mindrolling Trichens, or heads of the Mindrolling lineage, beginning with Jetsun Mingyur Paldrön (1699-1769). The current Jetsunma is Her Eminence Jetsun Khandro Rinpoche.

Nyingmapa in Exile

The Chinese invasion of Tibet and the 1959 uprising caused the heads of the major Nyingmapa lineages to leave Tibet. Monastic traditions re-established in India include Thekchok Namdrol Shedrub Dargye Ling, in Bylakuppe, Karnataka State; Ngedon Gatsal Ling, in Clementown, Dehradun; Palyul Chokhor Ling, E-Vam Gyurmed Ling, Nechung Drayang Ling, and Thubten E-vam Dorjey Drag in Himachal Pradesh.

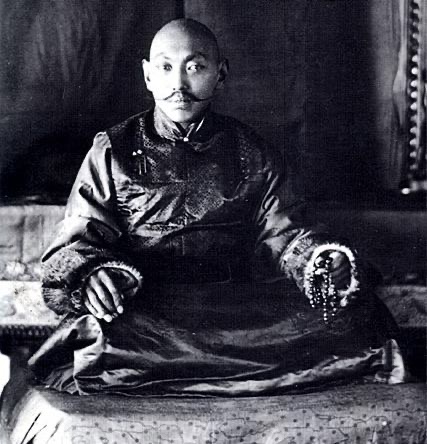

Although the Nyingma school had never had a head, in exile a series of high lama have been appointed to the position for administration purposes. The most recent was Kyabjé Trulshik Rinpoche, who died in 2011.

Reference

- O’Brien, Barbara. “The Nyingmapa School.” Learn Religions, Aug. 25, 2020, learnreligions.com/nyingma-school-450169.