Reading The Face magazine in early 1984 I was overwhelmed by a double-page spread entitled The New Glitterati featuring Leigh Bowery photographed in his ‘Paki from outer space’ look. His face was camouflaged in bright Plasticine-blue make-up, his head adorned with a mock leather military cap emblazoned in sequins and badges, while his entire body dripped with jewels, piercing and lots of body glitter. He wore a masterful creation – a bright green velour top with plunging neckline, fitted with this amazing red, asymmetrical zipper. Bowery looked like some exotic fashion god, a contemporary Krishna put through the blender with an extraterrestrial. It was kitsch and outrageous. It was inspirational. Did Jean Paul Gaultier, John Galliano or Vivienne Westwood design these clothes? Intrigued, I wanted to know more. The writer of the article observed:

One glance at these blinding photographs reveals why designer and jovial poseur Leigh Bowery – 22 years old, Abba addict and unrepentant champion of platform shoes – chose to leave his native Australia and cultivate his own outrageous style on the fringes of London’s club scene. They just didn’t understand him in the outback.1

I sighed … finally, an Australian designer had made it into the pages of this influential style journal. Bowery did more for Australian fashion in two pages than had occurred in the past century … and the best was yet to come.

An extra extrovert, the ultimate spectacle, the fashionable performer, the grand poseur, Bowery communicated through his blatant sexuality, his extreme physical exaggerations, and his outrageous dress codes. Bowery was not simply dressing up; it was his lifestyle and commentary on the mundane, a joke about appearance. His collections or ‘looks’ were based on himself manipulating his body with clothing and make-up. Working outside the comfort zone, he developed a clothing aesthetic that few would dare follow. Original, provocative, evolutionary; Bowery manipulated clothing to totally change one’s appearance, like a form of cosmetic surgery. ‘In an age when pop stars, actors, designers – those who traditionally dictated stylistic trends – are almost indistinguishable in their uniformity and blandness, Leigh Bowery stands out like an erection in a convent.’2

Leigh Bowery’s place in fashion, art and popular culture is seditionary. The fashions he created were not worn on the streets, very rarely seen in daylight, or generated for mass consumption. His dress style hailed from club culture,3 and the concepts of dressing up and masquerade.

Bowery was born in Sunshine – a baby-boomer, semi-industrial suburban sprawl, west of Melbourne – on 26 March 1961.4 He attended Sunshine Primary School and later, Melbourne High School. He passionately wanted to be a fashion designer and studied for two years at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) before becoming disillusioned by the restrictions imposed by formal training. Fuelled by the visual culture of style magazines, Bowery was attracted to London by the new romantic/blitz movement of the early 1980s where fashion, art and music were fused under the glamorous spotlight of the nightclub scene. Pop stars and bands such as David Bowie, Steve Strange, Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran and Culture Club influenced style. This was the breeding ground for the most creative, experimental and sexually charged clothing. Clubs were the stage for dressing-up; men and women wearing outlandish garments, big hairstyles and faces plastered with make-up. Gender boundaries were easily challenged in this world and androgynous looks abounded.5 Pretty clothes and special effects like frilly shirts, kilts, lace, satin and make-up were all worn by men – gay or straight – ‘it was almost like a love affair with yourself’.6 In the 1970s David Bowie, especially with his Ziggy Stardust persona, had ‘invented a whole language of art posing, he[‘d] invented the language to express gender confusion’.7 Fantasy and escapism were attractive vehicles to express individuality through clothing, make-up and hair. The key rationale for clubbers was attracting attention and being the centre of attention: dressing up was very competitive.

In 1984 the relaunch of London Fashion Week provided a platform for British designers to show their wares. This event, combined with vibrant street styles and the underground club scene, spawned the most creative and eccentric clothes, making London a potent source for world fashion trends. It nurtured and gained recognition for the fashion designers Vivienne Westwood, John Galliano, and in recent times, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan. However, it was clubs that provided the major venue, market and audience for generating clothing that was beyond one’s wildest dreams/nightmares.

Without working from ‘classics’, referencing the cultures of the world, fashions of previous decades or centuries, emulating a favourite designer or the current pages of French Vogue, Bowery was inspired to create something that bore no resemblance to anything. Early in his career he had begun to despise fashion because it was too restrictive and conservative. Bowery’s looks were incredibly fresh and up-to-the-minute fashionable. Making items over a short period of time, for a special event or club night out, his garments were a spontaneous response to the immediacy of his environment.

I believe that fashion (where all the girls have clear skins, blue eyes, blond blow-waved hair and a size ten figure and where all the men have clear skins, moustaches, short blow-waved hair and masculine physique and appearance) STINKS. I think that firstly individuality is important, and that there should be no main rules for appearance and behaviour. Therefore I want to look as best I can, through my means of individuality and expressiveness.8

Bowery’s costume designs were complex, technically difficult and fantastic. By 1985 they bore no similarity to the catwalk or street styles of London or the rest of the world. Vivienne Westwood initially was a great inspiration to Bowery, particularly her anti-establishment spirit, her distortion of clothing and body forms, and her design mantra that ‘clothing could be subversive’.9 Bowery garments were worn by performers like Boy George, who recalled:

I was dressed like a Jewish bathroom, gold chains, safety-pins, badges and buckles, champagne corks and tassels. The costumes designed by Judy Blame and Leigh Bowery were meant to hide my expanding girth, although it was hard to look thin in an A-line smock with angel-wings jutting out the back.10

In 1985 Bowery evolved from a fashion designer into an aesthetic revolutionary when he became the public face of the nightclub Taboo. The name said it all. Situated in the Maximus discotheque at Leicester Square, the club was originally staged only once a fortnight. Wearing a different outfit every week, Bowery was the main attraction. Some of his kitsch looks included a

short pleated skirt, with a glittery denim, Chanel-style jacket teamed with scab-make-up and a cheap, plastic, souvenir policeman’s hat11 … yellow gingham jacket printed with red spots with matching shirt and face12 … a denim jacket covered with Lady Jayne hair slides and his bald head decorated with dribbled dyed glue. The club’s dress code was ‘dress as though your life depends on it, or don’t bother’.13

The taste for the ridiculous, and his constantly changing looks, ensured that when Bowery entered the club, everyone else looked boring. Taboo was not an exclusively gay club, however, it attracted a large gay following lured by the opportunity to be part of the outrageous fashion scene. The Taboo nightclub symbolised the excesses of the 1980s, looking fantastic was taken to extremes. Unfortunately, it closed after a year due to drug soliciting. Boy George has turned this club phenomenon into the Broadway musical Taboo.14

Without the assistance of the slick, branded imagery associated with major fashion labels and huge marketing budgets, Bowery’s fame and reputation rested solely on being seen. His creations were documented and celebrated in the London style magazines, i-D, The Face and Blitz; his antics were reviewed in the club pages, communicating his visual language. Promoting the fringe, these magazines gave copy and editorial to the young and original, promoting an ideas culture that supported independent design.15 In Melbourne the enclave of independent fashion designers and boutiques situated in Greville and Chapel streets would proudly display the latest edition of The Face or i-D in the shop window, and they were indispensable reading in every hairdressing salon. Many Australians followed Bowery’s career and lifestyle through this source, even the interior of his flat that he shared with Trojan16 was featured – walls covered in Star Trek wallpaper, clumps of plastic flowers decorating the skirting, and UV-lit. Interviewer: ‘Does the interior of your home match the interior of your mind?’ Leigh and Trojan: ‘Yes, it’s an extension of what we wear.’17

Bowery was a great fan of the American film director John Waters whose movies had a profound effect on the development of his dress aesthetic, his humour and body politics. Waters pushed the boundaries of taste, making films with outrageous plots and an offbeat humour merged with an unseemly collage of characters, scenery and costumes. This ‘trash’ aesthetic is best portrayed in the film Pink Flamingos, 1972, about the search for the filthiest person alive, which was Bowery’s favourite movie.18 The principle actor, Harris Glen Milstead, working under the name Divine and affectionately known as the Queen of Sleaze, and a cult figure in his own right, was a cross-dresser. His huge physique was featured wearing figure-hugging gowns or sack dresses. The representation of the ‘fashionable’ unfashionable person was meticulously crafted, with huge, bouffant hairstyles and highly stylised make-up, reminiscent of the Kabuki theatre, accompanying Divine’s extensive wardrobe. This image of alternative, Baltimore glamour was one Bowery chose to follow.

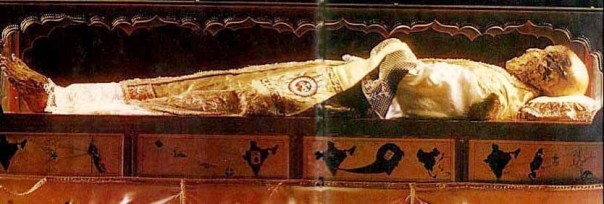

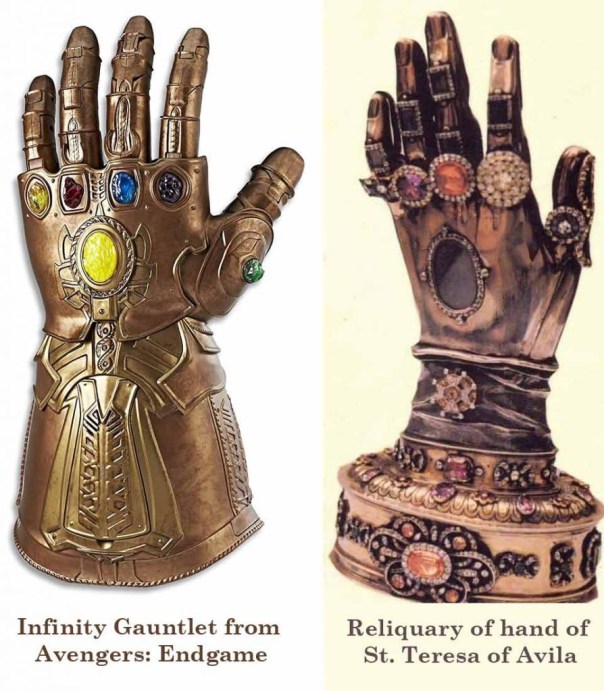

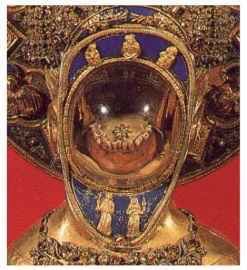

The magnitude of Bowery’s costumes is unforgettable, both in physical scale and psychological effect. The Metropolitan, c. 1988 – christened by Nicola Bowery in reference to its most famous appearance at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, at the opening of the Lucian Freud retrospective in 1993 – had been worn by Bowery to various events (figs 1–4,8)19 Like many of his fashioned items, The Metropolitan was a work in progress that would simply be upgraded or reaccessorised to suit the occasion. This dress reads like a masculine ballgown, it is not intended to be drag or transvestite costume. Gender bending was common in the 1980s; the most infamous example was the skirted male suit produced by Jean Paul Gaultier in 1985. It was an attempt to blur the distinctions between male and female dress, however, the translations into mainstream fashion were commercially unsuccessful.20

Forged from a garish floral sateen, The Metropolitan boy’s dress has a square, flat bodice with a right breast pocket and open underarms. The bodice extends into a full-face mask with cut-out holes for the eyes and mouth. The mask was a device Bowery employed to prevent ruining his clothes from greasy make-up stains; in Metropolitan he could apply make-up only to his eyes and lips. Using extensive metreage, the enormous skirt appears to hover, supported by a series of taffeta and tulle petticoats, producing a fashionable silhouette reminiscent of 1950s haute couture. Bowery was serious about the history of fashion and his private library contained many books relating to designers, including the major French couturiers Cristobal Balenciaga and Christian Dior, the pre-eminent role models who practised the very expensive, drop-dead-gorgeous philosophy of French high fashion. Restricted by money, Bowery still participated in fashion’s excesses by relying on inventive detailing and utilising entire bolts of inexpensive fabrics for the production of major works. His selection of ‘tasteless’, out of date, patterned prints purchased from discounted fabric shops defiantly challenged the grand-ballgown tradition. In this case, the floral motifs are enlivened with clusters of blue sequins painstakingly sewn on individually by Nicola Bowery in a mock Dior/Balenciaga style.21

Bowery was a professional dressmaker; he drafted patterns, cut fabric and sewed. His garments were solid constructions, strong enough to survive the rigours of clubbing. When he lived with the corsetiere Mr Pearl, they would purchase second-hand corsets, pull them apart and remake them to learn the exacting construction techniques.22

The Metropolitan is a total disguise, providing an obvious reference to traditions of fancy dress and masquerade,23 a perfect choice for a gallery opening depicting the wearer’s naked portraits! The art world was familiar territory; Bowery visited museums and he avidly collected art books and catalogues. Bowery even played the role of an art exhibit in 1988, performing at Anthony D’Offay’s London gallery wearing a different outrageous, tasteless, memorable look each day. Bowery desperately wanted his artware to be acknowledged by this elite. Nicola Bowery intentionally named this costume The Metropolitan in the hope that it would enter that prestigious collection.

In a rather perverse way, Bowery loved fashion protocols and niceties; wearing gloves, hats, belts and shoes. Gloves were a particular favourite and an expensive item to buy, so he would often steal these to complete his ensemble. Like the leader of a militant fashion army, Bowery walked into the Metropolitan wearing a floral dress with a Kaiser helmet, a pair of khaki camouflage-print gloves, a leather neck-and-waist belt and a pair of candy-pink platform shoes, and literally invaded the space. In all the fashion galas and openings held at the Metropolitan, no one had ever seen anything like this. His entrance would have been either very funny or very frightening. Just like a scene from a John Waters movie, he stole the show. Bowery’s exposure and main recognition in the mainstream art world came through the hauntingly beautiful, naked portraits of him painted by Lucian Freud. With his curvaceous, plump body and luminescent, waxed skin and his un-made-up natural face with pierced cheeks in-filled with clear plastic plugs, this was the Bowery the art-museum world could relate to.

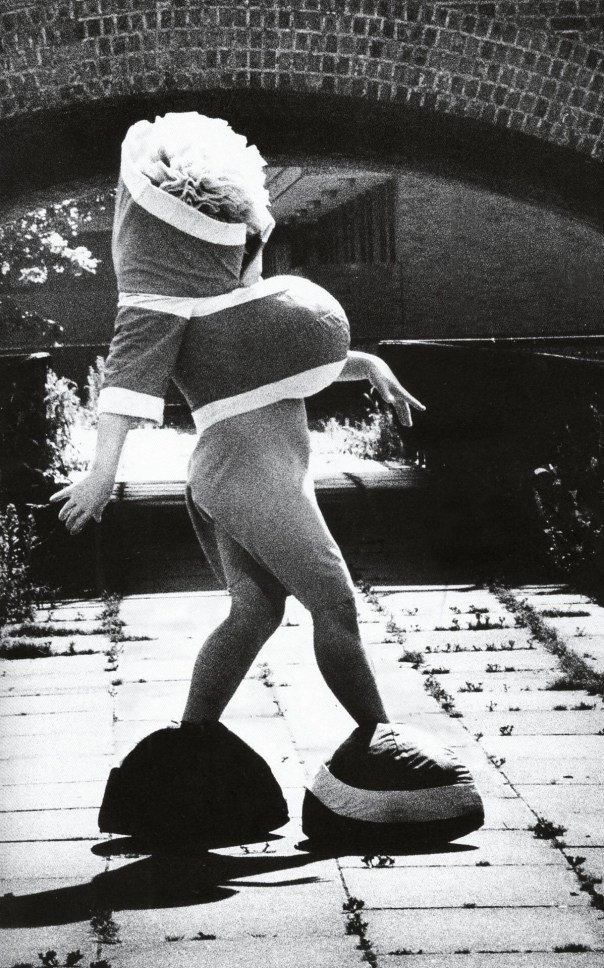

After 1990 Bowery stopped using fancy decorations on his clothing, instead, his work became much more abstract and surreal. During a trip to Japan he had discovered a catalogue of Transformer robots. These sophisticated toys provided a catalyst for Bowery to reconfigure his body and clothing in strange ways: he became a transformer. The Pregnant tutu head, c. 1992, costume is an experiment with scale and form (figs 5-7). Bowery in his performance pieces had already mesmerised his audience with giving birth to Nicola Bowery on stage.24 He was fascinated by the body’s capacity to change shape, and pregnancy was the most obvious example. Bowery’s clothing rituals often involved pain, discomfort and restrictions that produced difficulties with breathing, urinating and mobility. Although not intentionally designed for sadomasochistic pleasures, he applied any device, physical or manufactured, to achieve the masterpieces of his imagination, and this was pleasure enough.

Bowery had already attempted to distort his own body with unorthodox combinations of clothing forms and the deception of make-up. The Pregnant tutu head‘s top has a protruding belly suggesting the silhouette of a pregnant woman and the continuation of the species; it is worn with stretch pants. To continue this exaggerated silhouette and reinforce the symbol of growth, Bowery crafted half-circle, fabric shoes from large pieces of foam rubber covered in brown fabric. The bulbous shoes look ridiculous, like the cartoon models worn by Mickey and Minnie Mouse. The headpiece is formed like a large pompom made from tiers of orange tulle frills zipping up the back; the wearer encapsulated in a puff of fabric. A pair of full-length, dark blue gloves complete this ensemble. Bowery’s 1990s clothing is often visually disturbing, as he experimented with costume freakery.

Since his death in 1994,25 Bowery’s contribution to fashion and style culture has begun to be assessed and acknowledged in wider forums beyond style magazines and the club subcultures. Today, the boy from Sunshine is recognised internationally as a major style icon of the twentieth century, he was ‘surely a predictor of fashion!!!!’.26 Phaidon published The Fashion Book in 1998,27 a gigantic tome devoted to the 500 leading designers who had created and inspired world fashion over the past 150 years. Only three Australians made the final cut: Colette Dinnigan, Akira Isogawa and Leigh Bowery. Bowery’s recognition came not from commercial success or as a known fashion brand, but from his creativity and originality, described in the book as ‘part voodoo part clown’. He was indexed as an icon alongside the likes of David Bowie and Johnny Rotten. Bowery was not about setting fashionable trends, however, the influence of his creations is seen in the work of designers such as Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, and in the conceptual approach of much contemporary fashion, reinforcing the ‘continuing importance of this experimental dimension of fashion culture’.28

An exhibition of Leigh Bowery’s work was staged in Australia in 1999: Leigh Bowery: Look at Me at the RMIT Gallery, Melbourne, curated by Robert Buckingham and designed by Randal Marsh, included original costumes, videos and photographs. For many Australians this was their primary exposure to Bowery’s work in a local context,29 and certainly, to see actual costumes was provoking. Unexpectedly, these crafted, one-off garments designed for club wear and art performance were neither pretty, fashionable nor utilitarian. Instead, they had the power and capacity to confront issues relating to appearance, sex and politics. For many viewers this experience was a revelation. Bowery’s genre was as provocateur. The National Gallery of Victoria acquired two costumes from this exhibition and it is the only gallery in the world (at the time of writing) to represent his costumes.30 Bowery is finally an official part of Australia’s material culture.

Perhaps the best recognition and understanding of Bowery’s work is the inclusion of The Metropolitan in the inaugural hang at the Ian Potter Centre: NOV Australia, at a gallery devoted to Australian art. ‘Leigh would be ecstatic’ if he knew he was part of a major public collection.31

Reference & Notes

- Taboo or Not Taboo, the fashions of Leigh Bowery, NGV, 2 June 2014, by Robyn Healy https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/taboo-or-not-taboo-the-fashions-of-leigh-bowery/

This article focuses only on aspects of Bowery’s clothing design, in particular, the examination of his work in a broader fashion context, and does not attempt to cover his extensive repertoire, particularly his performance work or collaboration with the Michael Clarke Ballet Troupe.

1 L. White, ‘The new glitterati’, The Face, no. 48, April, 1984, p. 56. For a discussion of influence and role of the style magazine and fashion journalism see C. McDermott, Streetstyle: British Design in the 80s, New York, 1987, pp. 81–88; for an examination of the nature of fashion journalism see A. McRobbie, British Fashion Design: Rag Trade or Image Industry?, London, 1998, pp. 151–174.

2 A. Sharkey, ‘The undiluted Leigh Bowery’, i-D, no. 42, The Plain English Issue, June 1987, p. 63.

3 ‘Because clubbing and raving are done by a narrow segment of the population after most people go to bed, the scale of the social phenomenon often goes unnoticed.’ S. Thornton, Club Cultures, Cambridge, 1995 p. 14.

4 For a complete account of Bowery’s life, see S. Tilley, The Life and Times of an Icon, London, 1997; and R. Violette (ed.), Leigh Bowery, London, 1998.

5 S. Cole, Don We Now Our Gay Apparel, New York, 2000, p. 158.

6 ibid., p.159.

7 J. Savage, Time Travel, Pop, Media and Sexuality 1976-96, London, 1996, p. 112.

8 Tilley, p. 97.

9 McDermott, p. 26. Vivienne Westwood collaborated with Malcolm McLaren from 1971 to 1983 before embarking on a solo career.

10 B. George with S. Bright, Take It Like a Man, London, 1995, p. 521.

11 Tilley, p. 57.

12 ibid., p.61.

13 ibid., p.53.

14 Music and lyrics by Boy George, based on the story by Mark Davies. Directed by Christopher Renshaw. Matt Lucas, Boy George, and most recently, Marilyn, have played the role of Bowery.

15 T. Jones (ed.), Fashion and Style: The Best from 20 Years of i-D, Koln, 2001.

16 Pseudonym used by Gary Barnes, 1966–86, who described himself as an ‘artist and prostitute’. Encouraged by Bowery, he painted confronting works in a Daliesque/naive style. They lived together for several years, Bowery dressing him in his latest fashion designs.

17 F. Russell-Powell, ‘Penthouse’. i-D, The Inside Out Issue, no.19, October 1984, p. 8.

18 Nicola Bowery, discussion with the author, 23 May 2002.

19 N. Bowery, discussion, 17 July 2002. The Metropolitan was purchased from Bowery’s widow, Nicola Bowery. She generously donated Pregnant tutu head to the National Gallery of Victoria in 1999.

20 S. Mower, ‘Gaultier’, Arena, London, July/August 1987, p.85. Gaultier produced only 3000 suits worldwide.

21 N. Bowery, discussion, 23 May 2002.

22 N. Bowery, discussion.

23 See A. Ribeiro. ‘Fantasy and fancy dress’, Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe, New Haven, 2002, pp. 245–282. The custom of masking or disguise goes back to antiquity. ‘The masquerade provided opportunities for role-playing and subversion of propriety in defiance of the conventions of society’ Ibid., p. 245.

24 For photographs relating to Leigh Bowery’s performances, from Wigstock to his pop group Minty, and his performances with the Michael Clarke Ballet Troupe, see Violette.

25 ‘The fabulous Leigh Bowery passed away on New Year’s Eve, 1994, and London lost another mirror ball. No one knew Leigh had Aids because he didn’t want them to. He said, “I want to be remembered as a person with ideas, not Aids.”’ George with Bright, p. 566.

26 Walter Von Beirendonck, letter to the author, 14 June 2002.

27 The Fashion Book, London, 1998. See Leigh Bowery entry, p.70; Colette Dinnigan, p. 135; Akira Isogawa, p.225.

28 D. Gilbert, ‘Urban outfitting’, in Fashion Cultures: Theories, Explorations and Analysis, eds S. Bruzzi & P. Gibson, London, 2001, p. 9.

29 In 1987 Bowery performed with the Michael Clarke Ballet Troupe at the Melbourne Town Hall, horrifying his parents and most of the audience with his obscene acts.

30 Nicola Bowery, discussion, 17 July 2002.

31 Nicola Bowery, discussion.