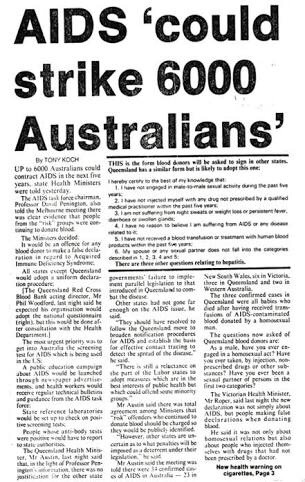

I discovered this older article recently while rummaging through my article archives. I present it here with some edits and newspaper inclusions. HIV & AIDS (note the separation of the two) has an intricate, but morbidly fascinating, national & international history. I watched “The Normal Heart” again only a couple of days ago, and the hospital scene where Felix is in the hospital ward with the meal sitting outside the door of his KS infected friend, and being told not to go in without contagion gear raised a whole plethora of unpleasant memories with me. To understand where HIV is now, you need to understand where it was!

I can’t believe it has been about thirty seven years since we first started hearing about HIV/AIDS. I find it even harder to believe that I have been infected for thirty five years. Over half my life has been lived with this virus! In personal retrospection, I could say that compared to the bad, bad old days of 1981, life is a bed of roses today. But then I am aware that quite a lot of people would still not share that sentiment, so out of respect to them, I will avoid such romanticism.

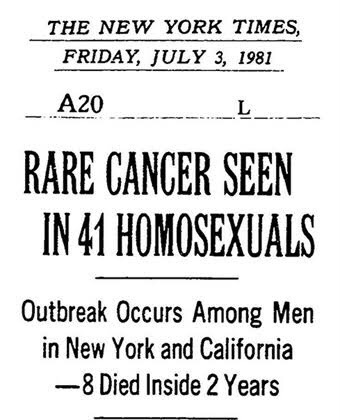

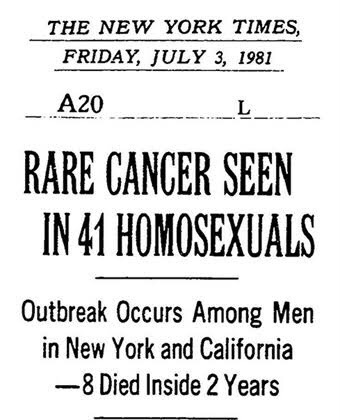

I was living in Melbourne at that time, and I believe that HIV/AIDS got its first mention in the gay press a little earlier than 1981, though I could be wrong. There were only snippets, overseas briefs if you like, of a strange STD that seemed to be selectively attacking the San Francisco gay community, or more specifically, those members of that community who frequented the baths and back rooms of the famous city. I know that no one here was particularly concerned. We thought it was just another of ‘those American things’, or just a mutated form of the clap. Nothing that a pill wouldn’t fix! By the time I returned to Sydney in 1982, we had started to think quite differently. Some of us were getting very scared!

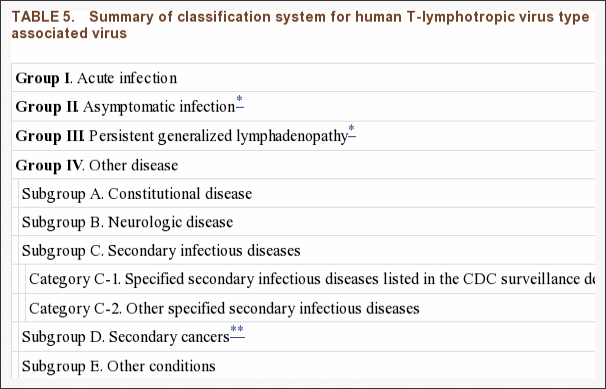

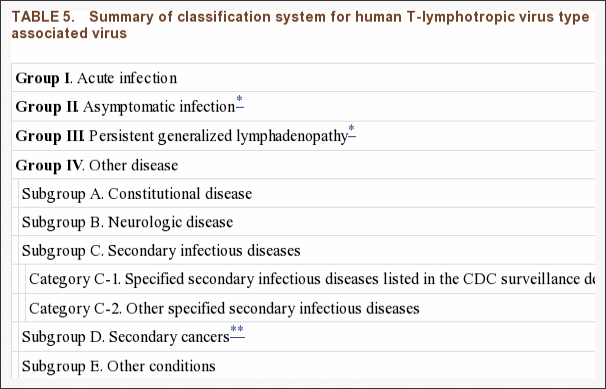

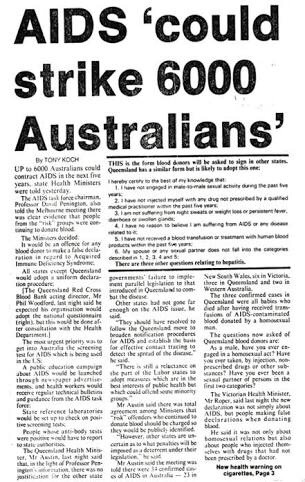

The media began drowning us in information, mainly from the United States. There was the dramatic scenario of ‘Patient 0’, from whom it was assumed the whole epidemic had spread like an out of control monster. The USA and France argued over who had discovered the virus, and made the link between HIV infection and AIDS (watch “Dallas Buyers Club” for an inkling of what this was all about!). A debate raged as scientists tried to decide what to call it and which acronym to use. We had GRID (Gay Related Immune Disease) and HTLV 1 & 2 (Human Transmitted Lymphoma Virus – if memory serves me well). They eventually settled on HIV for initial viral infection, and AIDS for any subsequent illnesses that resulted from the breakdown of the immune system. The original Center for Disease Control (CDC) classification system for the various stages of HIV and AIDS progression was so complicated that you really needed a university degree to be able to decipher them. To make things more manageable they finally settled on four classifications.

Then came ARCs (AIDS Related Conditions) but that was considered politically incorrect, so we settled on OIs (Opportunistic Infections).

The argument over names and classifications wasn’t half as frightening as the reality of the disease itself, which started to hit home in 1985. Official testing began in that year, and is still the earliest date that medicos will accept as a point of diagnosis with HIV. Any date earlier than that is declared to be a ‘self-report’. Like many others, I assumed I was HIV+ long before testing started. Virgin and chaste were not words to be found in my life resume. Sydney’s Albion Street Centre was the first here to begin testing, and it was done very discreetly and anonymously. We all used an assumed first name, and were issued with a number to identify who we were. (In 1996, when I needed to tap into my first HIV test results done at Albion Street, they were still there.) Counseling was atrocious. You were given your HIV+, or HIV- (if you were lucky) status very bluntly, then quickly shunted over to a counsellor before the shock had a chance to set in. You were also told, almost apologetically, that you probably had about two years to live. That was HIV diagnosis circa 1985.

A number of our conservative politicians, and some of our outraged Christian clergy started to say that they wanted us placed in quarantine. It was very specifically a gay disease, according to them, and they truly believed that fencing off the gay areas of Sydney and leaving it to run its course could contain it. These people wondered why we got tested anonymously!

By 1985 people were starting to die. There were no dedicated HIV wards in any of our hospitals, and patients were shuttled between temporary beds in wards and the emergency department. Reports started to filter through of hospital staff wearing contagion suits around patients with HIV. Worse still, meals were being left outside the doors of rooms, and would often be cold by the time the patient managed to get them. Cleaners refused to clean the rooms. There were scares of infection by contact with everything from a toothbrush, to a glass, to cutlery, so patients were offered very disposable forms of hygiene. Even mosquito’s copped some of the blame.

Then, of course, we had the living daylights frightened out of all of us with the “Grim Reaper”television ads. From 1985 to 1995, death lived with us on a daily basis. If you weren’t visiting sick friends, lovers, or partners in hospital, you were visiting them at home, or attending their funerals and wakes. Most of us lost the majority of our friends, and for most of us those friendships have never been replaced.

Around that time, the gay community took charge of what was quickly becoming an out-of-control situation. Tired of seeing friends dying in emergency wards, and getting only the minimum of care at home and in hospitals, we established our own care, support and advocacy groups. Out of the pub culture grew groups as diverse as BGF, CSN, ANKALI, ACON, and PLWHA. Maitraya, the first drop in centre for plwha was founded, and we raised the first quarter of a million dollars through an auction at “The Oxford” Hotel to start to improve ward conditions at St. Vincent’s Hospital. The gay community can forever take great pride in itself for bringing about great changes, not only in the care of plwha, but in the way the disease was handled, both politically and socially..

The Department of Social Security streamlined people with HIV/AIDS through the system and onto Disability Support Pensions, and the Department of Housing introduced a Special Rental Subsidy so that those on a Pension, and unable to wait interminable amounts of time for housing, were able to live in places of their own choice, at greatly subsidised rent. Home care became available through CSN, which, at that time, was not a part of ACON. By 1992, there was a perceived need for improved dental services for HIV patients, especially considering the high incidence of candida. The United Dental Hospital led the way with a HIV Periodontal Study, which at last provided reasonable dental care to plwha.

The first vaccine, p24VLP, was trialled with absolute zero results. There were quite a number of scares with HIV contaminated blood, and screening of blood donors was tightened. Discrimination reared its ugly head in the Eve van Grafhorst case, which forced this poor little girl to not only leave her school because of the hysterical reaction to her HIV infection, but to flee the country with her family.

In 1987, the first therapy for AIDS – azidothymidine (AZT) – was released in the USA, and its use in patients with HIV/AIDS was fast-tracked through the approval process here. In France a huge trial called ‘The Concord Trial’ was conducted – unethically – and its findings were found to be inaccurate. The resulting announcement that AZT was ineffective in the control of HIV, and the drug nothing more than ‘human Rat Sak’, caused a universal outcry. The damage was done. Many had no faith in the new drug at all, and local activists and proponents of alternative therapies tried to encourage people not to use the drug. Many of us chose otherwise. True, the effects of AZT were short-term only – maybe six to twelve months – but many saw it as a way to keep the wolf from the door long enough for some other drugs to come along. And come along they did. AZT was quickly followed by what are referred to as the ‘D’ drugs – d4T, ddi, ddc, and the outsider 3TC. However, these were all drugs from one class called Nucleoside Analogues and all had short effectiveness. Some doctors tried giving them in double combinations, but the effectiveness wasn’t much better. Despite their short life span, these drugs were being prescribed in enormous doses, which resulted in problems such as haematological toxicity, anemia, and peripheral neuropathy. We needed a miracle! Add travel restrictions in many countries, blood transfusion infections, and some babies dying as a result of this and things weren’t looking good!

Those of us who had managed to survive to 1996 were starting to give up hope. Most of us were on a pension, had cashed in and spent our superannuation and disability insurance, had a declining health status, and didn’t hold out much hope for a longer survival time. Prophylaxis for illnesses such as PCP, CMV, MAC and candida had helped improve most people’s lives, but they didn’t halt the progress of the virus. The first of the Protease Inhibitors, Saquinavir, was introduced that year, and evidence started to emerge of the effectiveness of combining the two classes of drugs into what came to be known initially as ‘combination therapy’ and later as HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy). The results were astounding; those close to dying suddenly found their CD4 counts rising, accompanied by a return to reasonable health. Viral Load testing was introduced and people were finding not just a raising of their CD4 counts, but a drastic lowering of their viral load, often to the point of its being undetectable. This became known amongst doctors as ‘the gold standard’. Ganciclovir Implants to assist with the control of CMV retinitis were trialled the same year, and Albion Street Clinic started a trial using decadurabolane, a steroid, to assist in controlling Wasting Syndrome. The new drug combinations (NNRTI’s – Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptease Inhibitors – a third class of drugs, were introduced shortly after) were not without their complications and problems. Most combinations still required huge quantities of pills to be taken daily, not just of the HAART drugs, but also prophylaxis and drugs to help control side effects such as nausea and diarrhoea. Their use required time and dietary compliance. Other problems such as lipodystrophy, lipoatrophy, and renal problems appeared, but we were, despite any drawbacks, a lot better off than we had been ten years, hell even two years earlier.

People’s health changed drastically, and suddenly new services started to take prominence. Some people required lots of counselling to help them reconnect with the life they thought had been taken from them. Others went to peer support groups or turned to treatment management groups, and some to the larger range of support services being provided by The Luncheon Club, The Positive Living Centre, NorthAIDS and other similar groups. There was recognition that there was a need for services to assist people with an improved health status, as some of them were contemplating returning to work. Despair had, to a large extent, been replaced by hope. Organisations concerned with people’s changing needs reassessed and changed their services to meet the demand. Those that changed have survived, and are still prominent in our community.

The war is far from over. New generations require new strategies, and while everyone seems happy that infection rates for HIV have remained steady in Australia (despite rampaging out of control in Third World countries), many feel it is still not good enough that, at this stage of 37+ years into HIV/AIDS, countries like Australia with high levels of education and accessibility to media and information should be seeing a decline in infections. Remembering my own youth I find it difficult to comment on the attitudes of young people. I grew up through the very worst that HIV/AIDS had to throw at us, and the lessons it taught are not easy to forget. I have to ask myself had I not had that experience, how would I be viewing it? It is no longer just the responsibility of the gay community to guard against new infections. Responsibility also rests with the straight community, and the IDU community, as infection rates remain at their current level. Some scaremongers have ventured forth theories of a ‘third wave’ of infection, but I trust we are too wise, and too educated to allow that sort of irresponsibility to happen.

Many of us (certainly not all) are going on to lead relatively normal lives. Many have returned to work either as volunteers, or in casual, part-time or full-time employment. Many like myself have returned to tertiary education, determined not to leave this world without at least fulfilling some gnawing ambition. However, we are not living in a ‘post-AIDS’ world, and to think so would be foolish. Even if the battles have been won at home, they still need to be fought elsewhere. We still need new drugs, and we still need people to trial both the emerging antiviral and opportunistic infection drugs and the immune-based therapies. We now have a fourth class of drugs in the form of Nucleotide Analogues. Many medical practices have adopted a holistic approach to medicine, and this can be judged to be a direct spin-off from the HIV/AIDS wars. Hopefully, soon please, a new vaccine will appear.

I really don’t know how much longer I will live now. Certainly with the standard of health care I get, and the close monitoring, I may live out whatever my allotted time was to be. Time will be a better judge of that than I will. For me, HIV/AIDS has been a two-edged sword. It has taken good health from me, I have permanent disabilities from AIDS, and I have seen far too many friends, lovers and partners die from this hideous disease. At the same time, it has presented me with opportunities I would never have grasped if it had not come along. I am re-educating myself, taking myself off along strange paths. It has given me a whole new understanding not just of HIV, but of disabilities in general, and a great respect for those who overcome difficulties and recreate their lives.

At a university tutorial last semester, a young woman asked me if I thought every day about having HIV. I don’t! It may have taken thirty five years, but it is now so integrated into my life, that I have trouble remembering the time when I didn’t have it. The pills are just pills now (and thankfully a lot less of them than even 4 years ago), and most of my current medical problems have more to do with ageing than with HIV.

I can tell you, that really gives me something to think about!

Tim Alderman (C © Revised 2017)