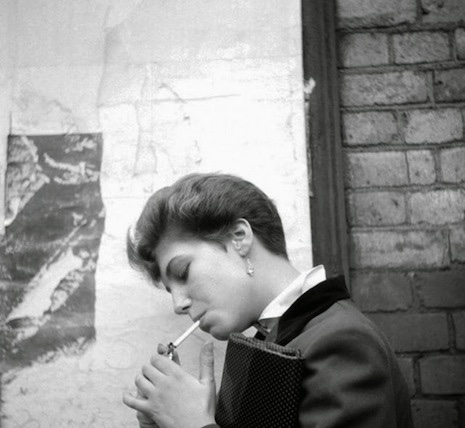

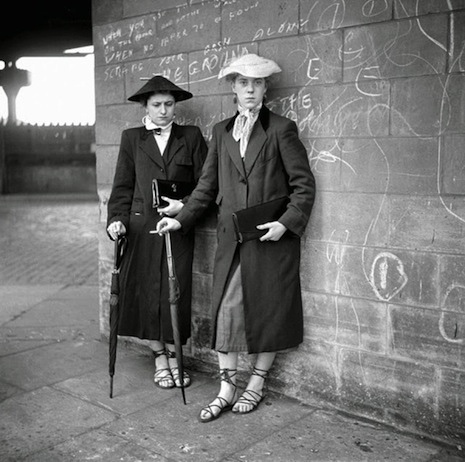

We trace the history of the 50s girl gangs that rebelled against austerity, trading in their ration books for Edwardian frills.

The Last of the Teddy GirlsPhotography by Ken Russell

On reflection, the paring of the aristocratic flamboyancy of an Edwardian gent with the rebellious attitude of American rock and roll shouldn’t have worked – but it did. This sartorial hybrid, engineered by the Teddy Boys of the 1950s and later adopted by their feisty female counterpart, Teddy Girls (also known as Judies) – created a strangely alluring visual identity, one which set them apart from their contemporaries in a decade where youth culture was finally carving out an aesthetic of its own. Sharply-suited Teds (whose name derives from ‘Edwardian’) might look remarkably smart to a contemporary eye – particularly when positioned against fellow groups of teenagers, like the punks who threatened to puncture the fabric of society with their safety pins – but their reality was more rebellious than it initially seems.

Like the gangs of youths who’d pace the streets in Dr Martens or Reebok Classics in decades to come, the odd report of fights quickly led to the sweeping generalisation that all Teds were trouble. In response, some venues implemented “no Edwardian dress” policies that echoed the “no trainers or football colours” door criteria of today. Contrary to what one might assume, smart dress didn’t make the Teds more respectable – it actually rendered them intimidating, in the same way that a suited Al Capone could coolly induce panic with a tip of his straw boater. “I remember my dad would threaten me for not doing what I was told by saying he would set the Teds on me,” remembers Magnum photographer, Chris-Steele Perkins who went on to photograph the second wave revival of the teds in the seventies.

The Last of the Teddy GirlsPhotography by Ken Russell

Rebellious Decadence

The Teds had a put-together smartness that at first feels at odds with the idea of a rebellious teenager, but they were, in fact, ripping up the rulebook (or ration book, as it were) by rejecting the austere approach of a post-war economy. Their decadence was also a two fingers up to the ruling class, as the Teds took ownership of the Edwardian Drape jacket – which was marketed by Savile Row tailors to young Mayfair men in 1949 – much to the horror of the posh boys: “Absolutely the whole of one’s wardrobe immediately becomes unwearable,” complained one. Despite the aristocratic origins of the dandyish Drape, this item was almost always thrifted by the Teds, else paid for in incremental instalments. The Teddy Boys and Girls originated from then working-class areas in East or West London, areas still bearing the wounds of the war with still-to-be rebuilt bombsites punctuating their areas. After an era of fashion taking a back seat to function, what better way to sartorially rebel than with the impractical frivolity of a tiny clutch bag; the must-have accessory for a Teddy Girl?

The Last of the Teddy GirlsPhotography by Ken Russell

Working Girls

Most Teddy Girls left school at 14 or 15, taking secretarial jobs in London, or working in factories on the outskirts. Their hard-earned cash was not wasted on expensive clothes, as original London Teddy girl Mary Toovey – who, herself worked in the Kegoo factory having left school at 15 – told writer Eve Dawoud: “Turn-up jeans, a coat and something to tie around your neck, those were the Teddy Girl essentials. My friends and I would buy similar clothes when we shopped on the Portobello Road. It was all second hand then, we couldn’t afford new. Smart’s, the local pie and mash shop on Goldborne Rd, was where we went to eat out if we had the money.”

Toovey was photographed by Altered States Director Ken Russell, who documented a group of Teddy Girls local to him in Notting Hill. It was thought the images were lost forever but they were uncovered in 2005. “No one paid much attention to the Teddy Girls before I did them, though there was plenty on teddy boys,” He recalled. “They were tough, these kids, they’d been born in the war years and food rationing only ended in about 1954 – a year before I took these pictures. They were proud. They knew their worth. They just wore what they wore.”

The Last of the Teddy GirlsPhotography by Ken Russell

Androgynous New Age

Perhaps more significant than the boy’s subversion of upper-class clothing was the girls’ appropriation of masculine styles. Whilst the pants worn by working women during the war were mostly shed in relief, replaced by the welcome femininity of silhouette-skimming skirts, the Teddy Girls clung to the new sartorial codes that the adoption of menswear for women ushered in: boxy single-breasted jackets and the slicked back quiff hairstyle, a proto-mohawk that would eventually give way to the more extreme hairstyles of punk. Despite their non-conformist style and rebellious attitude, “I never thought of those kids as anything but innocent,” Ken Russell told The Evening Standard. “Even the Teddy Girls [from the 1955 series The Last of the Teddy Girls], all dressed up, were quite edgy, and that interested me; they were more relevant and rebellious — but good as gold. They thought it was fun getting into their clobber, and I thought so too.”

TThough Ken Russell wanted to be a ballet dancer, his father wouldn’t hear of it—no son of his would ever be seen in tights—so the young Russell turned his attention to photography, a craft he thought he could make his name with. He attended Walthamstow Technical College in London, where he was taught all about lighting and composition. Russell would later claim that everything he did as a trainee photographer broke the rules—a trend he continued throughout his career as a film director when producing such acclaimed movies as Women in Love, The Music Lovers, The Devils, Tommy, Altered States and Crimes of Passion.

Russell became a photographer for Picture Post and the Illustrated Magazine, and during his time with these publications took some of the most evocative photos of post-war London during the 1950s. He spent his days photographing street scenes and his nights printing his pictures on the kitchen table of his rented one-bed apartment in Notting Hill.hough Ken Russell wanted to be a ballet dancer, his father wouldn’t hear of it—no son of his would ever be seen in tights—so the young Russell turned his attention to photography, a craft he thought he could make his name with. He attended Walthamstow Technical College in London, where he was taught all about lighting and composition. Russell would later claim that everything he did as a trainee photographer broke the rules—a trend he continued throughout his career as a film director when producing such acclaimed movies as Women in Love, The Music Lovers, The Devils, Tommy, Altered States and Crimes of Passion.

Russell became a photographer for Picture Post and the Illustrated Magazine, and during his time with these publications took some of the most evocative photos of post-war London during the 1950s. He spent his days photographing street scenes and his nights printing his pictures on the kitchen table of his rented one-bed apartment in Notting Hill.

All above photos by Ken Russell

Reference

- THE LAST OF THE TEDDY GIRLS’: KEN RUSSELL’S NEARLY LOST PHOTOGRAPHS OF LONDON’S TEENAGE GIRL GANGS, Dangerous Minds, 13 February 2015, Posted by Paul Gallagher https://dangerousminds.net/comments/the_last_of_the_teddy_girls_ken_russells

- Teddy Girls: The Style Subculture That Time Forgot, AnOther Mag, 25 November, 2015, text by Laura Havlin https://www.anothermag.com/fashion-beauty/8064/teddy-girls-the-style-subculture-that-time-forgot